Memory of Spanish Refugees: Dispatch from Septfonds, France

This summer, traveling by winding roads through darling villages and rolling hills of sunflowers and alfalfa, I took a detour from vacation in the Tarn et Garonne region of France and made my way to the town of Septfonds. Septfonds is an important site of memory in the story of the Spanish Republican exodus, for it is the place of an internment camp originally built to contain a tidal wave of Spanish Republican refugees in January 1939. The Septfonds camp is one of a number of places in France where Spanish refugees and Eastern European Jews crossed paths in their respective resistance to and flight from Nazi terror.

As France faced an unprecedented refugee crisis after the end of the Spanish Civil War, General Ménard, the officer of the military region of Toulouse, was entrusted with the logistics of how to contain the Spanish exiles. He wanted to limit the number of camps in the area of the Pyrénées Orientales, so he decided to open six large units to contain 100,000 refugees on the Spanish border, Septfonds among them.

In a requisitioned, large sheepherding pasture in the department of Tarn et Garonne, the camp came to hold 16,000 Spaniards, crowded into sheds covered with thin corrugated roofs.

The living conditions were terrible, as they were in many other camps for Spanish refugees: the exiles lacked clean water, heating and electricity. Approximately 81 refugees died early on from disease and, in some cases, overwhelming emotional anguish. A simple and beautiful Spanish Cemetery, on the other side of the village, contains the remains and headstones of the Spaniards who perished at the internment camp.

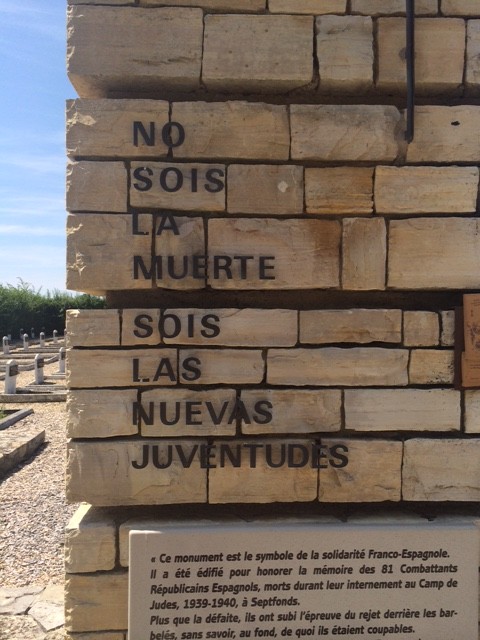

I set out on the July morning looking for the remains of the camp and the cemetery. Upon entering the village of Septfonds, I readily found the signs to the “Cimetière des Espagnols.” I followed a side street and after a few blocks came across the gate to the burial place…quiet, noble, with only the sun, mooing of cows in a pasture alongside, and a gentle breeze as my guides. The lone visitor, I pushed open the gate and saw before me two large stone monuments framing the entrance and engraved with verses by the Republican poet Rafael Alberti:

¿Quién dijo que estáis muertos? Se escucha en el silbido

que abre el vertiginoso sendero de las balas

un rumor, que ya es canto, gloria recién nacido,

lejos de las piquetas y funerales palas.

Y los vivos, hermanos, nunca se les olvida.

Cantad ya con nosotros, con nuestras multitudes

de cara al viento libre, a la mar, a la vida.

No sois la muerte, sois las nuevas juventudes.

[Who said you are dead ? You hear the whistle

opening the dizzying trail of bullets

a rumor, already a song, a newborn glory,

far away from the picks and funereal shovels.

And the living, my brothers, they never forget you.

Sing with us, with our multitudes

Our faces to the wind, to sea, to life.

You are not death, you are youth ascending.

One stele in French, the other in Spanish. The 81 gravesites look upon us dignified in their simplicity; white marble gravestones with black plaques, each man’s name engraved in gold. The stones have no dates of birth or death. I felt the aching, brutal calamity that befell the Republican men, all of whom died within a few short months. The visitor’s office in Septfonds provides a small brochure that lists biographical details of the deceased, so that one can walk among the graves and learn more about the men buried there. I read in French of the men, their families, their military affiliation, the cause, hour and location of death:

Léandro Ballestas Sarsa âgé d’environ 25 ans. Fils de Ballestas et de Sarsa. Milicien espagnol réfugié, 48ème brigade ferroviaire. Décédé d’une pleurésie purulente, Boulevard de la République le 18 mars 1939 à 12h40; Carlos Garcia Cerezo âgé d’environ 20 ans. Fils de Garcia et de Cerezo. Milicien espagnol réfugié 1er groupe de mitrailleur, bataillon 108. Décédé de la typhoïde, Boulevard de la République le 19 mars 1939 à 8h.

My own tears took me by surprise when I came to the grave of José Gines Moles: âgé d’environ 25 ans. Fils de Gines et de Moles. Milicien espagnol réfugié. Décédé de misère physiologique, Boulevard de la République le 23 mars 1939 à 7h30. A young Republican militiaman succumbed to his broken heart.

As I closed the gate behind me, I felt appreciation for the volunteers in Septfonds who maintain this peaceful site of memory and who proudly feature the history of Spanish Republicans as integral to their own identities as anti-Fascists. The Septfonds web page brings home just how important the Spanish narrative is in the World War II story of the region.

Now it was on to try to find the site of the former camp itself, “Camps de Judes.” My GPS took me in circles; I lost track of the signs to the camp. I finally asked a young farmer–in my broken French–if he could help me find the memorial. He informed me that I was on it! I had arrived at an abandoned pasture. What remains of the once extensive barracks are a single rebuilt model barrack and a number of explanatory plaques in a semicircle bordering an open expanse.

I learned that not all was death and sorrow at the camp. Indeed, the Spanish Communists maintained an active political and artistic life during their detention. Children went to school, and refugees worked on nearby farms. Later, Spaniards from the camp joined the French war effort serving in foreign-worker details.

Like so many of the former internment camps on French soil, Septfonds held people from various nationalities who faced unequal and, often deadly destinations (especially in the case of the Jews). The Spaniards came and left; Poles arrived at Septfonds; Spaniards returned in 1940 as part of foreign worker groups made up of Republicans and many demobilized foreign workers who were Jews. Thus it is here, in Septfonds, as in other parts of France, where Jews fleeing Nazi persecution met up with Spaniards.

By 1942, Septfonds was put to its ultimate and most sinister use, as Jews from the region fell to French Nazi collaborators during round-ups. In total, 295 Jews detained in the region were transferred from Septfonds—to Drancy, and on to their deaths at Auschwitz.

For more on the history of Septfonds and the establishment of the Spanish Commentary and the memorial at Septfonds:

http://www.septfonds.com/septfonds_espagnols_decedes_01.htm

http://www.cheminsdememoire.gouv.fr/en/septfonds-internment-camp

http://www.septfonds.com/septfonds_camp_judes01.htm

Gina Herrmann, one of ALBA’s Vice-Chairs, teaches at the University of Oregon.