HR COLUMN: Youth Protest and Human Rights

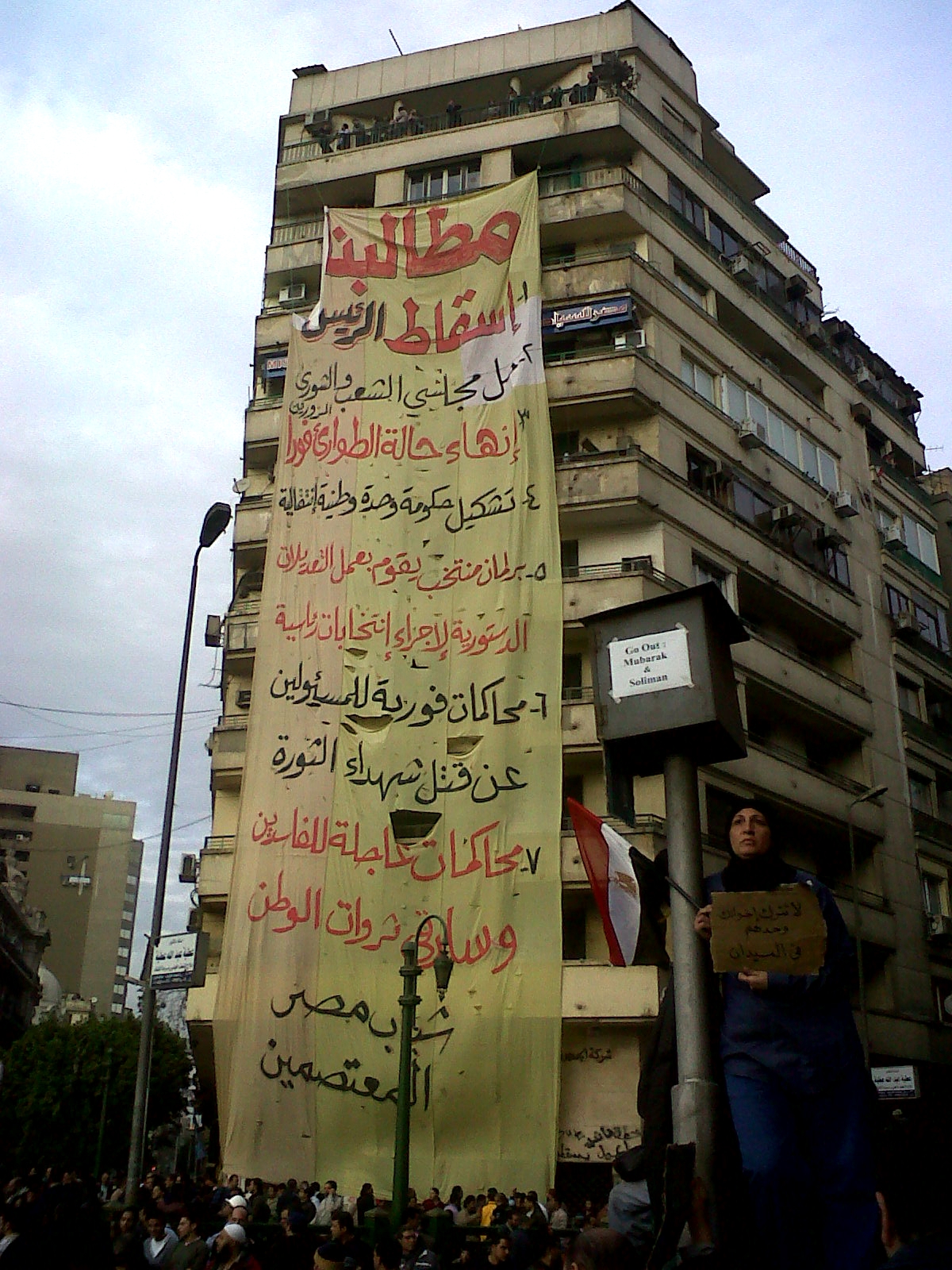

Youth protests in Tunisia, Egypt, Chile, Spain, the United Kingdom, the United States, Turkey, and Hong Kong, have served to reveal the connection between oppressive states and the inequitable economic practices they sponsor.

Four years ago, Mohammed Bouazizi, a Tunisian street merchant unable to obtain licenses to operate his business without local harassment, immolated himself in desperation. His death set off protests throughout the Arab world and sparked a two-year series of youth demonstrations, lasting through 2013, that were remarkable for their scope and intensity but also for their use of social media such as Facebook and Twitter. Yet today, one might argue that the central lesson of those events is a sobering one: systematic political reform is nearly impossible to achieve in a short period of time. Indeed, when examining the political activities of contemporary youth in response to authoritarian states and drastic inequality, it is easy to view their use of social media and newer technologies as little more than navel gazing. Others see young people as feckless as their predecessors of other eras, unable to fight the good fight for fundamental social and political change. Looking back at the Arab Spring and the protests it encouraged, however, I find these assumptions seriously deficient on a number of accounts.

Neoliberal and authoritarian practices have created a degree of systematic inequality that has harmed the vast majority of the world’s population.

No doubt neo-liberal and authoritarian practices have created a degree of systematic inequality that has harmed the vast majority of the world’s population in ways that assault basic survival and the right to live a life of dignity. It is particularly galling that such inequality was produced while corporations, the financial sector, and state-sponsored crony capitalists operated with impunity. But it is also true that youth protests in Tunisia, Egypt, Chile, Spain, the United Kingdom, the United States, Turkey, and most recently Hong Kong, have served to reveal the connection between oppressive states and the inequitable economic practices they sponsor. No longer can populist anger in opposition to such practices be dismissed as class warfare, as it was prior to 2011. No longer can the authoritarian practices of states be uncritically condoned as having been born out of economic necessity. This is an important achievement for which the youth who were involved in protest should take credit.

There can also be little doubt that through their use of new social media and technologies, young people have found a powerful means to communicate with one another. They have expanded their voice to address a global audience, and used the new media to motivate large numbers of their peers to participate in active protests in Tunis, Cairo, Barcelona, Madrid, New York, Santiago, Phnom Penh, Istanbul, Manama (Bahrain), and Hong Kong. Indeed, Spanish sociologist Manuel Castells has argued that networking processes at their very core create a possibility for political organizing that is new and exciting. Such organizational flexibility was most clearly in evidence during the Spanish Indignados movement, and during the Zucotti Park protests that were part of the U.S. Occupy Movement.

Networking processes at their very core create a possibility for political organizing that is new and exciting.

It is simply untrue that beyond engaging in a few protest activities, youth are unwilling to articulate a consistent commitment to structural change. Around the world, we see the growth of “netizens” and citizen journalists who are using the Internet and social media to investigate and report on corrupt practices in settings as diverse as Bahrain and China, despite government efforts to restrict their activities. In Chile, two of the student movement’s most visible and articulate leaders, Giorgio Jackson and Camila Vallejo, now hold public office. In the United States, Occupy members became active in offering assistance to victims of Hurricane Sandy and have more recently supported efforts to address climate change. And in Cambodia, proponents of democratic reform using social media came extremely close to ousting one-party authoritarian rule in the national elections of 2013. It is clear that the information age has offered youth new opportunities to practice “engaged citizenship,” fueling important discussions outside the confines of traditional institutional spaces, including schools, churches, and families. It is also clear that the level of engagement is serious and constant.

Although not all contemporary youth protests have risen to the level where they can be described as viable social movements, they certainly have been able to frame their actions in compelling ways. The fact that Hong Kong youth appropriated the “Occupy” language to define their protest movement says a great deal about the power of ideas and the means through which they are expressed. The Hong Kong Occupy Movement thus confirmed in 2014 that a deep concern with basic human rights continues to shape the thinking of youth wherever they reside.

The fact that Hong Kong youth appropriated the “Occupy” language to define their protest movement says a great deal about the power of ideas and the means through which they are expressed.

Contemporary youth protests touch upon our shared values with regard to equity, dignity, and justice. These values have been articulated in many contexts over many generations. To be sure, social memory is recursive and not always linear. Efforts to account for past injustice emerge under unpredictable and often surprising circumstances. Today’s youth have demonstrated that they understand this all too well. But in their enunciation of human rights values, they express a level of commitment in line with the efforts of their predecessors.

Irving Epstein is the Director of the Center for Human Rights and Social Justice and Professor/Chair of the Educational Studies Department at Illinois Wesleyan University. His edited volume The Whole World is Texting: Youth Protest in the Information Age will be published in 2015.