From Guernica to Human Rights: The shifting paradigms of the Spanish Civil War

Writers and soldiers alike saw Spain as the first battlefield of World War II. In the title essay of his new book, excerpted here, historian Peter N. Carroll traces the war’s legacy, from the shocking bombing of the Basque town of Guernica by German and Italian air forces to the attacks on civilians and displacement of refugees in later wars. The stories about the Spanish Civil War that remain to be told may establish a foundation for a new paradigm involving matters that today we call human rights.

Ernest Hemingway with Ilya Ehrenburg and Gustav Regler during the Spanish Civil War, not dated, circa 1937. Hemingway Photograph Collection, John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum, Boston. Public Domain.

Writing to his mother from Spain in 1937, Hyman Katz, an American volunteer in the International Brigades, pointed to the rise of Mussolini and Hitler and the spread of anti-Semitism in Europe: “Seeing all these things—how fascism is grasping power in many countries (including the U.S., where there are many Nazi organizations and Nazi agents and spies)—can’t you see that fascism is our problem—that it may come to us as it came in other countries?” Canute Frankson, a Jamaica-born auto mechanic, wrote to his “Dear Friend” from Spain: “if we crush Fascism here we’ll save our people in America, and in other parts of the world from the vicious persecution, wholesale imprisonment, and slaughter which the Jewish people . . . are suffering under Hitler’s Fascist heels. . . .” And Carl Geiser, writing to his brother in Ohio, said “The reasons I am here is [sic] because I want to do my part to prevent a second world war. . . . And because all of our democratic and liberty-loving training makes me anxious to fight fascism and to help the Spanish people drive out the fascist invaders sent in by Hitler and Mussolini.”

These U.S. volunteers in the Spanish Civil War, together with their 2,800 comrades who formed the Abraham Lincoln Brigade, knew exactly what they were fighting for. To them the defense of the Spanish Republic against a military rebellion led by General Francisco Franco was part of a global battle between democratic peoples and fascist aggressors. The generation that fought the Spanish Civil War is nearly gone, and its history passes into the hands of younger generations whose sense of history is shaped in different times. If it is true that each generation writes its own history—because each generation asks different questions of the past—we might pause and consider what issues and questions appear most relevant to our own times.

After World War II, the Francoist view emerged as a dominant idea in Western Europe and the United States, as a new Cold War ideology supplanted the notion that the Spanish Civil War was an anti-fascist war.

While Spanish Republicans fought a war against the military rebels who were backed by troops and munitions from Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy, the Nationalist or Franco side saw the war as a crusade against social disorder, secularism, and democracy—reduced rhetorically to a war against socialism, communism, and anarchism. After World War II, the Francoist view emerged as a dominant idea in Western Europe and the United States. Indeed, a new Cold War ideology supplanted the notion that the Spanish Civil War was an anti-fascist war. Instead, scholars and the general public stressed the equivalence of fascism and communism, Hitler and Stalin. It was this view that led President Ronald Reagan on his visit to Spain in 1983 to say that the American volunteers had fought on “the wrong side.” This Cold War interpretation has outlived the Cold War. But I would suggest that the twenty-first century will see new ways to explain the events in Spain. […]

The Hungarian writer Arthur Koestler provides an interesting case study of how historical interpretations change, particularly regarding his own participation in the Spanish Civil War. In 1937, the Left Book Club in London published Koestler’s memoir under the title Spanish Testament. His narrative is divided into two parts. The first describes Koestler’s journey to Spain, purportedly as a journalist, then flashes back for seven chapters of Spanish history that contextualize the civil war. Part two is subtitled “Dialogue With Death” and describes Koestler’s arrest, his months on death row in a fascist prison, and his lucky rescue.

In part one, Koestler argues that the most popular, current view of the causes of the Spanish Civil War “is the one that maintains that Spain is the battle-ground of a struggle between ‘reds and whites,’ between Communism and Fascism.” And he adds: “This is an entirely erroneous view.” Rather, he insists, the reforms of the Spanish Republic aimed to overcome a long history of political and economic oppression. He depicts the bombing of Madrid by Franco’s air forces as a low point in Western civilization. And his terrifying captivity—during which each evening he waited for a knock at the door summoning him to his death—appears as the direct result of Franco’s fascist, murderous terror. That is what he means by Spanish Testament.

Koestler returned to France, via Gibraltar, in 1938, still loyal to the Communist Party. But he was fatigued by the internal intrigues and political double-talk and disillusioned by news of Stalin’s terror, and he finally disavowed communism and the Soviet Union after the signing of the Nazi-Soviet non-aggression pact in 1939 […].Koestler’s classic novel, Darkness at Noon, published in London in 1941, reflects his political conversion. The totalitarian jailers are no longer fascists, but communists.

By 1942, as German armies stormed toward Stalingrad, Koestler’s political conversion was changing his historical paradigm, witnessed by the re-publication of portions of his Spanish Testament. Under the title Dialogue with Death, he stripped the book of the historical context. He also deleted one sentence from the first edition referring to the Barcelona May Days of 1937, which had criticized the P.O.U.M.—the Trotskyist Party. In its place, he added the following sentence: “It looked as though Spain were not only to be the stage for the dress-rehearsal of the Second World War, but also for the fratricidal struggle within the European left.” In a recently re-issued edition of Dialogue With Death, the American critic Louis Menand praises the de-contextualization of Koestler’s narrative: “If it included details about Koestler’s assignment in Spain, it would be a fascinating but dated text—a document, rather than the expression of something about the human condition.” The opposite of history, the opposite of remembrance, might be called amnesia. What has disappeared from the narrative is fascism.

Like Arthur Koestler, George Orwell revised his views on Spain during World War II: “The outcome of the Spanish war was settled in London, Paris, Rome, Berlin—at any rate, not in Spain.”

Like Koestler, George Orwell revised his views on Spain during World War II. Homage to Catalonia (1938), which recounts how the Communist Party crushed the social revolution in Spain, was not published in the U.S. until 1952, where it became part of the Cold War canon. Much less known is Orwell’s 1943 essay “Looking Back on the Spanish War,” which maintained that the “much-publicized disunity” within the Republic “was not a main cause of [its] defeat”: “the Fascists won because they were the stronger; they had modern arms and the others hadn’t.” “The outcome of the Spanish war,” he stated, “was settled in London, Paris, Rome, Berlin—at any rate, not in Spain.” Orwell didn’t abandon his anti-communism, but neither did he forget which sides were at war in Spain.

Another writer whose reputation in relation to the Spanish Civil War has been buffeted by the political winds is the novelist Ernest Hemingway[…], who did some remarkable things on behalf of the Republic that are practically forgotten or unknown.

Hemingway with Joris Ivens and Ludwig Renn in Spain, 1936. Bundesarchiv Bild 183-84600-0001, CC BY-SA 3.0.

Consider two of them. The first is related to the pro-Republican documentary The Spanish Earth, on which Hemingway collaborated with the Dutch filmmaker Joris Ivens. Hemingway’s companion and accomplice in Spain was the writer Martha Gellhorn, a courageous journalist for Collier’s magazine and, coincidentally, a close friend of Eleanor Roosevelt. When the film was completed in 1937, Gellhorn arranged for a private screening at the White House in July. […] Of course, the purpose of screening a propaganda film in the White House was to awaken the interest of the most powerful man in the nation […]. Hemingway’s effort is significant. Although Roosevelt admitted that the Republic was a “vicarious sacrifice” for the world, he did not change his position on the arms embargo.

The novelist also undertook a secret and ambiguous project for the Spanish Republic, which can now be confirmed for the first time on the basis of a previously unpublished letter he later wrote to the poet Edwin Rolfe, a veteran of the Lincoln Brigade […] in January 1940, as he was nearing the end of writing For Whom the Bell Tolls:

O.K. Once I had to go to a town will not name to check personally (knew many people there) on effect of something that happened from the air and it’s true effect. Also on possibility of rising there. How much dough. And to carry dough. Was scare[d] pissless all the time, really scared, woof because there is an indignity in that kind of finish that scares long in advance. On return had to report that they (1)-hate our guts. 2. It would be pouring dough down a rathole. 3-Didn’t trust the bastard[s w]ho were handling what there was. O.K. Report was considered defeatism of the deepest dye. Only was true and save much lives and money.

The point to emphasize is that Hemingway perceived the Spanish Civil War as a war against fascism. He certainly suspected the machinations of Republican leaders and was no fool about the chicanery of the Communists. But much as Britain and the United States collaborated with the Soviet Union during World War II, Hemingway insisted that the first order of business was winning the war. A few years later, when he read a draft of the screenplay of For Whom the Bell Tolls, he was appalled that the movie, released in the middle of World War II, gave no clue to explain why “a man will die and know it is well for him to die.” “We are at present engaged in fighting a war against the Fascists,” he said. “Throughout the picture the enemy should be called the Fascists and the Republic should be called the Republic. . . . Unless you make this emphasis the people seeing the picture will have no idea what the [Spanish] people were really fighting for.”

The views of Hemingway, Orwell, and Koestler […] reflect important political alignments. The failure of Hemingway and Gellhorn to influence U.S. policies revealed deep fissures within President Roosevelt’s coalition. His hands were tied not only by non-interventionists who opposed any international entanglements, but also by the position of his own Catholic constituents, who had followed the Vatican’s endorsement of the Franco rebellion. Three months after seeing The Spanish Earth, the president attempted to counter what he called “isolationism” in what became known as the Quarantine Speech of October 1937. Warning of the “epidemic of world lawlessness,” he called for a quarantine against aggressor nations. The speech drew so much criticism that Roosevelt dared go no further. It’s a terrible thing,” he said, “to look over your shoulder when you are trying to lead—and to find no one there.” […]

U.S. textbooks of the 1940s and 1950s usually describe Franco’s Spain as a fascist dictatorship, linked to Hitler and Mussolini. Charles Beard, in his 1944 history of the United States, summed it up as follows: Roosevelt supported British nonintervention, while “fascist rebels were demolishing the Spanish Republic . . . and by doing so he aided, if unwittingly, in the triumph of fascism there.” Such ideas were common in the 1940s. But as the Cold War politics rehabilitated General Franco, the views of history changed and the space devoted to the Spanish Civil War diminished. Equally important, the war was seen not as a struggle between an elected government and a fascist rebellion but as a fight between two totalitarian systems, communism versus fascism—a prelude not to World War II, but to the Cold War.

Writers like myself, consciously or not, are obliged to respond to the Cold War narrative in order to restore the historical context in which participants in the Spanish Civil War acted.

This second paradigm continues to dominate historical writing in America, not only from the anti-communist scripts that see the Spanish Republic merely as an instrument of Soviet policy but also from writers like myself who, consciously or not, are obliged to respond to the Cold War narrative in order to restore the historical context in which participants in the Spanish Civil War acted.

In writing about the similarity of several documentary films about the Lincoln Brigade, my colleague Anthony Geist recently observed that the prevailing story is a “response to an unacknowledged master narrative that hovers, unspoken, over all these films, and that is the discourse of the Cold War.” The cinematic counter-narrative focuses on issues that Cold War–influenced writers have introduced as evidence of communist hypocrisy, opportunism, even subversion, and argues for different interpretations.

To use one of Geist’s examples, since part of the anti-communist position emphasizes that communists were “un-American,” the counter-narrative stresses the indigenous nature of U.S. communists and places their story in the framework of particular ethnic or nationality groups. In my own work, for instance, Hy Katz speaks for the many Jewish volunteers who had reason to fight Hitler’s allies; Canute Frankson for African Americans; Evelyn Hutchins for women. In addition, the volunteers appear not as Communist Party ideologues, but as independent thinkers who boldly cut against the grain of Roosevelt’s neutrality policies. Such works play down the role of the Communist Party or the sectarian splits among leftist groups. Meanwhile, exponents of the Cold War narrative snipe at these works and scrutinize new archival discoveries for proof of communist evil.

We are heading toward a new paradigm that pays more attention to diverse source materials and that appreciates multiple perspectives.

I don’t think this argument is going to end soon. But I do think that we are heading toward a new paradigm that pays more attention to diverse source materials and that appreciates multiple perspectives. The FBI files about the Lincoln volunteers, for instance, reveal the prejudices of both the federal investigators and the subjects of investigation. When a “Negro” man danced with a white woman at a Lincoln Brigade party, the FBI saw subversion (which, of course, it was, given the times). But the agents’ concern about misused passports cannot be dismissed as mere bigotry. Nor can we deny that some members and veterans of the International Brigades acted as informants and spies to assist the interests of the Soviet Union […].

The FBI files about the Lincoln volunteers reveal the prejudices of both the federal investigators and the subjects of investigation.

I believe that new paradigms will move away from the national histories of the brigades and address issues of internationalism. Among U.S. volunteers, for instance, a significant number—at least 300—have Spanish surnames, indicating direct ties to Spain and Latin America, regardless of ideology. Puerto Rican, Cuban, and Filipino volunteers had reasons for going to Spain without reference to party politics; so did the Jewish men and women who seem to have traveled disproportionately from many parts of the world. The history of the war also needs to address the diaspora of Spaniards after Franco’s victory and their resistance to fascism during and after World War II. The Spanish Civil War is broader than its national boundaries.

Among U.S. volunteers, for instance, a significant number—at least 300—have Spanish surnames, indicating direct ties to Spain and Latin America, regardless of ideology.

In addition to the military narrative that focuses on soldiers, battles, and casualties, I believe it is essential to examine the “home fronts,” both within Spain and in countries that responded to the Franco rebellion. In the United States, for instance, there is evidence that citizens of various persuasions participated in activities to aid the Republic or petitioned Washington to support their favored side. We know, too, that some communities, especially the Spanish immigrant groups or multi-ethnic cities like New York, were severely divided in their opinions. We know that Spain mobilized opinion throughout the Americas and served to break through the narcotic of isolationism. The effect of Spain on the public consciousness […] is critical for understanding the idealism that drove support for the big war against fascism that soon followed—even though we know that whatever the Allied commitment to internationalism was, in 1945 the great powers turned their backs on Spain.

The story that remains to be told and may establish a foundation for a new paradigm involves matters that today we call human rights. Paul Preston’s path-breaking book, The Spanish Holocaust, focuses on internal Spanish politics in those terms. We must remember that not only soldiers went to Spain to save the Republic, but also medical professionals, social workers, and humanitarians. Dr. Leonard Crome, a British doctor in Spain and in World War II, is honored by an annual lecture, which provided the opportunity for this essay. Similarly, no American volunteer showed greater heroism than Dr. Edward Barsky, who founded the American Medical Bureau to Aid Spanish Democracy, served as a frontline surgeon and a rearguard fundraiser for the Republic, and headed the postwar Joint Anti-Fascist Refugee Committee. For these efforts, he was thanked by the government with a one-year jail sentence and loss of his medical license because he refused to turn over the names of donors and recipients of humanitarian aid that, he knew, would find their way into Franco’s hands.

The story that remains to be told and may establish a foundation for a new paradigm involves matters that today we call human rights.

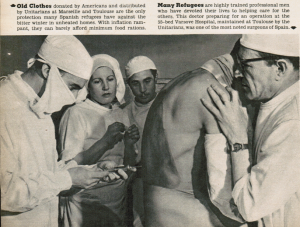

Humanitarian campaigns, then and now. Above, a photo by Walter Rosenblum for Liberty magazine of exiled Spanish doctors attending to a refugee in Southern France after World War II. Below, a photo of Doctors without Borders for its Syrian campaign (source.

Doctors Crome and Barsky were two of thousands of world citizens who responded to the horrors of civilian bombings and forced migration of refugees, the killing of the innocent, and the sheer terror of war, by volunteering as health workers, reporters, and good Samaritans. Others stayed home and raised funds to purchase medicine, condensed milk for children, or ambulances, or wrote letters to newspapers and pleaded with politicians to intervene, warning that Spain foreshadowed a world war, and implicitly predicting what we understand today as the worst genocide of the twentieth century. Spain was the beacon ignored, the lesson unlearned by leaders of so-called democracies but not ignored or forgotten by millions of their constituents.

When at last Roosevelt and Churchill came to talk about their principles and ideals in the Atlantic Charter of 1940, they expressed the importance of people’s right to self-determination and enunciated their commitment that “after the final destruction of the Nazi tyranny,” they hoped to see “a peace which will afford to all nations the means of dwelling in safety within their own boundaries, and which will afford assurance that all the men in all the lands may live out their lives in freedom from fear and want.” The Four Freedoms laid the basis of the postwar United Nations and the Declaration of Human Rights for each and every one of us. They did not anticipate how a cold war would create everlasting uncertainties of nuclear annihilation and strategic bombings of helpless populations. We’ve lived to see the tragedies of Spain repeated until they seem normal.

For all the squabbling about interpreting the Spanish Civil War, however, what is undeniable is the enduring interest in that conflict. Picasso’s Guernica immortalizes a tragedy that lives on in the twenty-first century. When the United States won the votes in the United Nations Security Council to invade Iraq in 2003, the diplomats took pains to cover up the nearby tapestry of that painting, fearing, justifiably, that the horrors of Spain would haunt their endeavors. The aerial bombing of civilians no longer troubles the universe, as it did three-quarters of a century ago in 1937. Nor does the never-ending flow of civilians from the ravages of war stop the wars. We have become inured to those terrors. But it was not always so. Every generation writes its own history because it struggles to understand its worst fears and its failures.

Peter N. Carroll is ALBA’s Chair Emeritus. This essay was adapted from the title chapter of his new book, From Guernica to Human Rights: Essays on the Spanish Civil War (Kent, OH: 2015). Earlier versions were presented as the annual Leonard Crome Memorial Lecture at the Imperial War Museum in March 2012, the Susman Lecture in New York in March 2013, and at Stanford University in October 2013, and published in the Antioch Review (Fall 2012).

Copyright © 2015 by The Kent State University Press. Reprinted with permission.

From Guernica to Human Rights: Essays on the Spanish Civil War can be pre-ordered by calling 800-247-6553. Use code FGHR for a 10% discount.