Human Rights Column: The hard lessons of the DNA exonerations

The era of DNA has changed the face of criminal justice forever. DNA tests have contributed to the exoneration of hundreds of innocent individuals —and exposed a deeply flawed system. Maddy deLone, executive director of the Innocence Project, makes the case for science-based judicial reform.

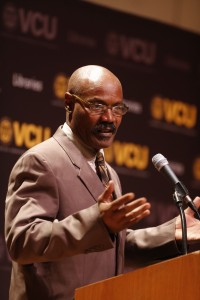

Marvin Anderson speaking at the Virigina Commonwealth University in 2013. Photo courtesy of VCU Libraries.

Marvin Anderson served 15 years of a 210-year sentence and three years on parole, for a rape, before he was exonerated in 2002 by DNA evidence. The victim was a white woman who had been attacked by a black male. Anderson, who is black, became a suspect in the case simply because he was known by the police to have dated a white woman. He had no prior criminal record, but police included his work identification card, which was in color, in a photo spread that included the black and white mug-shot photos of five other men. Not surprisingly, Anderson was selected. Within an hour of the photo spread, the victim was asked to identify her assailant from a live lineup. Anderson was the only person in the lineup whose picture was in the original photo array. Her memory having been tainted by the earlier photo, the victim wrongly selected Anderson again.

Wrongful convictions are hardly a modern phenomenon. Until recently, however, an injustice had little hope of being righted. The era of DNA has changed the face of criminal justice forever, having not only contributed to the exoneration of hundreds of innocent individuals but also exposed a system that is deeply flawed. Each time an innocent man or woman walks out of prison, the public’s confidence in the ability of the system to administer justice fairly is weakened.

Since 1989, 316 innocent individuals have been exonerated by DNA evidence, including 18 prisoners who served time on death row. These are not insignificant numbers, but sadly they represent only a small portion of wrongful convictions because DNA testing can only help in a small fraction of cases. Law enforcement experts estimate that testable DNA evidence is available for less than 10% of violent felonies, to say nothing of the many non-violent crimes for which many people are incarcerated. In addition to limited available evidence, there exists a large backlog of actual innocence cases and a limited number of individuals who can allocate sufficient time to look into these claims. In other words, the DNA exonerations represent only the tip of the iceberg.

How many innocent people are in prison? We will never know. Just the question itself is haunting, reflecting the now common knowledge that there are undeniably more innocent people languishing behind bars than we will ever find and free. However, even if as few as 1% of prisoners are innocent (a very low estimate in light of the many studies that have been conducted on the subject), it would mean that a staggering 22,000 innocent men and women are incarcerated in America’s jails and prisons for crimes that they did not commit.

Fortunately DNA exonerations have generated dramatic learning moments about the root causes of wrongful convictions. Eyewitness misidentification, false confessions, faulty forensic evidence, police and prosecutorial error and misconduct, inadequate defense lawyers and incentivized informant testimony are the most common contributors.

Stories like Anderson’s are all too common among DNA exonorees. Nearly 75% of wrongful convictions later overturned by DNA testing were caused at least in part by eyewitness misidentification. Just as science is helping us to uncover these terrible miscarriages of justice, it is also helping us to prevent them from happening in the first place. Scientists have been studying memory and identification for more than three decades and have developed proven reforms that make police identification procedures more reliable. The Innocence Project has helped to persuade state and local policy makers to adopt more reliable identification procedures and other science-based reforms across the nation.

Stories like Anderson’s are all too common among DNA exonorees. Nearly 75% of wrongful convictions later overturned by DNA testing were caused at least in part by eyewitness misidentification. Just as science is helping us to uncover these terrible miscarriages of justice, it is also helping us to prevent them from happening in the first place. Scientists have been studying memory and identification for more than three decades and have developed proven reforms that make police identification procedures more reliable. The Innocence Project has helped to persuade state and local policy makers to adopt more reliable identification procedures and other science-based reforms across the nation.

When the organization was founded in 1992, not one state had a law granting access to post-conviction DNA testing of evidence to prisoners; now, every state has one. Similarly, nine states have now adopted identification reforms and 23 require mandatory recording of interrogations. Moving forward, the Innocence Project has its sights on improving some of the other egregious flaws in the system, such as those stemming from the tremendous volume of people processed through an overburdened system that cannot provide the time to treat each individual as a person, let alone do the work that would better protect the innocent.

Mistakes are inevitable in any system, and the criminal justice system is no exception. However, when life and liberty are at stake, errors must be treated as learning opportunities. It is possible to minimize the risks of convicting the innocent without undermining the prosecution of the guilty, and in order to achieve this there is still work to be done in recognizing and reforming the various systemic weaknesses that can cause wrongful convictions to occur in the first place.

Maddy deLone is Executive Director of the Innocence Project (www.innocenceproject.org), a national litigation and public policy organization dedicated to exonerating the wrongly convicted through DNA testing and reforming the system to prevent further injustice. Marvin Anderson currently serves on the Board of the Innocence Project and is the Fire Chief in Hanover, Virginia.