Book Review Spain’s violence: An English woman’s view

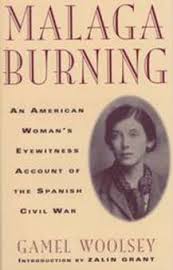

Málaga Burning: An American Woman’s Eyewitness Account of the Spanish Civil War By Gamel Woolsey. Introduction by Zalin Grant. 204 pages. $22. (Reston, VA: Pythia Press, 1998.)

Málaga Burning: An American Woman’s Eyewitness Account of the Spanish Civil War By Gamel Woolsey. Introduction by Zalin Grant. 204 pages. $22. (Reston, VA: Pythia Press, 1998.)

Spanish Civil War literature is replete with expatriate philosophizing about the Spanish character as a response to the violence of 1936-1939. Robert Jordan, of Hemingway’s For Whom the Bell Tolls says:

What sons of bitches from Cortez, Pizarro, Menéndez de Avila all down through Enrique Líster to Pablo. And what wonderful people. There is no finer and no worse people in the world. No kinder people and no crueler. And who understands them? Not me, because if I did I would forgive it all. To understand is to forgive. That’s not true. Forgiveness has been exaggerated. Forgiveness is a Christian idea and Spain has never been a Christian country. It has always had its own special idol worship within the church. (354-355)

Gerald Brenan wrote in The Spanish Labyrinth: “Where there was envy of the rich (and Spaniards are a very envious race) it took the form of desiring to bring them down almost as much as raising themselves” (xvi).

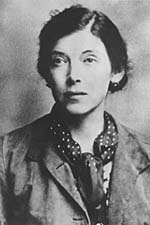

Gamel Woolsey, a lesser-known writer, also wrote of the Spanish “character” and tried to reconcile her love and appreciation for the Spanish people with the chaotic and merciless violence of the Civil War. The poet and her husband, historian and writer Gerald Brenan, lived in Churriana, Málaga at the outbreak of the conflict. Both wrote about this surreal, horrifying, and heart-wrenching experience: Brenan in his famous history, The Spanish Labyrinth (1943) and much later, more intimately, in his memoir, Personal Record 1920-1975 (1975). Gamel Woolsey published a less well-known memoir, Death’s Other Kingdom in 1939, which would later be re-released as Málaga Burning in 1998 by Pythia Press (and from which edition the quotes here are taken). It has been translated into two Spanish editions (Málaga en llamas, Temas de Hoy, 1998, and El otro reino de la muerte, Ágora, 1994, 2005), and has enjoyed great success in Málaga in the 21st century. Antonio Banderas, originally from Málaga, was intent on adapting the book into a movie, a plan that never came to fruition due to complications regarding the rights to the manuscript.

Woolsey’s work begins in the garden with a detailed description of “the most beautiful day of the summer” and ends in Portugal with sadness, anger and disillusionment, as Brenan and Woolsey are forced to flee the village they had come to love. Unlike the works of her expatriate contemporaries, Woolsey includes very little historical or political analysis. This is a book about feelings and personal realities. Woolsey carefully recounts day-to-day life in this deceivingly idyllic Mediterranean town, as death and violence gradually intrude and turn her world upside down.

Woolsey’s work begins in the garden with a detailed description of “the most beautiful day of the summer” and ends in Portugal with sadness, anger and disillusionment, as Brenan and Woolsey are forced to flee the village they had come to love. Unlike the works of her expatriate contemporaries, Woolsey includes very little historical or political analysis. This is a book about feelings and personal realities. Woolsey carefully recounts day-to-day life in this deceivingly idyllic Mediterranean town, as death and violence gradually intrude and turn her world upside down.

Brenan and Woolsey hide Spanish aristocrat Don Carlos Crooke Larios and his family for months in their house and help him escape the anarchist riots. They observe members of their quiet village turn against one another. They receive word of servants, friends, and acquaintances who are killed. Woolsey dreams of turning her house into a hospital and helping the wounded. From a tower in her house she watches Nationalist rebels bomb the city of Málaga, located about 15 kilometers from Churriana. She and Brenan go to Torremolinos and listen to various canards about the Spanish people from other foreigners. Everyone in their house listens to the angry words of General Queipo de Llano on the radio as he threatens to obliterate the masses.

Woolsey does not take political sides, but rather laments and condemns human violence, empathizing with victims of all ideological persuasions. She does not describe the violence of the war as uniquely Spanish, but rather as human. What brings her most to despair is the depreciating and entitled attitude of the British and American expatriates observing and condemning the war and the Spanish at a safe distance in Gibraltar. While she does make some observations about the passionate Spanish “character,” found in nuns and anarchists alike, the work uniquely focuses on the female rather than male Spanish character and subject. She writes:

A great deal of the character for which the Spanish are famous, I think, is found most of all in its older women. They have suffered and resigned themselves, worked beyond their strength, spent themselves for others. This patient stoicism, a stoicism that is not hard but gentle and quietly resigned, accepting life as it is with all its ills and griefs with dignity and without complaint, is one of the most remarkable of Spanish characteristics. And it has been seen a thousand times everywhere in Spain during the war.

Woolsey, who lived most of her life in the shadow of a famous man, notices and recognizes the women in the background.

Today, a visitor can view the historical setting of the book, as the Ayuntamiento de Churriana has restored Brenan and Woolsey’s farm-house and transformed it into a cultural art center, inaugurated in September 2013. Every room has been named after a famous person who visited there. As members of the Bloomsbury group in London, the couple entertained literary figures such as Virginia Woolf and Bertrand Russell in the house. One room has been dedicated exclusively to works of art representing Brenan, Woolsey, and their friends. Churriana has changed a great deal since 1936, especially with the construction of the neighboring Málaga International Airport. Traces of its earlier delights and charms still remain, and the town affords spectacular views of the Málaga mountains and countryside. Though the Ayuntamiento was unable to buy the entire original garden, the view from the tower, where Woolsey first spied the burning and bombing of Málaga, allows the visitor a glimpse of its original grandeur.

While many residents of Churriana recall Brenan as cold and aloof, Woolsey, known in Churriana as “La señora,” is remembered as a kind, caring, and empathic person– exactly the kind of sensitive author this short memoir suggests. While Brenan’s Spanish Labyrinth has been superseded by other historical analyses of the war and is long out of print, Woolsey’s Death’s Other Kingdom still speaks to the people of Málaga. The Spanish edition is sold in bookstores, perhaps because it uniquely records ordinary life in Málaga in 1936, and gives a simple subjective emotional truth about the war.

Woolsey intentionally named the work Death’s Other Kingdom in reference to T.S. Eliot’s poem about World War I, “The Hollow Men,” because she wanted to condemn the violence she observed in 1936. After Woolsey’s death, the title was changed to make the work seem more appealing. Whatever the name, the work deserves to be part of the Spanish Civil War literary canon. It is a different kind of historical document, one offering an outsider view of the war, a much more sensitive one—one that notices and observes– that feels deeply (rather than analyzes) the destruction of a great community of people.

Katherine Stafford teaches Spanish literature at Lafayette College in Easton, Pennsylvania.

This is a very welcome reprint of Woolsey’s underrated book. Gerald Brenan’s Spanish Labyrinth is, though, still in print and available as a CUP ‘Canto’ paperback. It has, deservedly, never been out of print since its publication in 1943