The Lincoln Brigade: A legacy of racial justice

Some ninety African-Americans joined the Lincoln Brigade in Spain. They came from urban inner cities in the north and the rural south; they were sharecroppers, labor organizers, mechanics, laborers, merchant seamen, and students. They all shared a commitment to justice and equality.

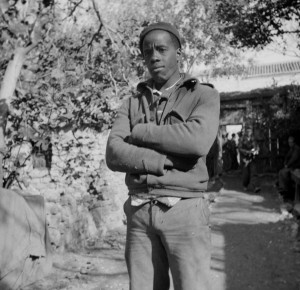

Al Chisholm in Spain, November 1937. (Tamiment Library, NYU, 15th IB Photo Collection, Photo #11-0653.)

I must keep fightin’/Until I’m dyin’. . . Paul Robeson sang these lyrics to “Old Man River” in a concert at the Royal Albert Hall in London in December 1937, changing Hammerstein’s original verses, I’m tired of livin’/An’ scared of dyin’, words to which he would never return. By Robeson’s own admission he was thinking of Spain when he sang these lines –I must keep fightin’/Until I’m dyin. . . —and within a month he would visit that country in the throes of its bloody Civil War. It was a turning point in his life.

We are here today to honor Bryan Stevenson with the ALBA-Puffin Award for Human Rights, in recognition of his tireless and brilliant work for economic and racial justice. What are the links that allow me to mention Paul Robeson, a war that raged on the southern flank of Europe nearly 80 years ago, and Bryan Stevenson in the same breath?

When Paul Robeson visited Spain in January 1938 he met a number of the 2800 young Americans known as the Abraham Lincoln Brigade who volunteered to fight fascism in that country. They in turn were part of the International Brigades, 35,000 of them who came from 52 different countries to defend democracy from the assault by Franco, Hitler and Mussolini. Among the American volunteers were some 90 African-Americans.

They came from urban inner cities in the north as well as the rural south of the United States. They were sharecroppers, labor organizers, mechanics, laborers, merchant seamen, and students. They all shared a commitment to justice and equality that led them to offer their lives to achieve those goals.

Al Chisholm said that he volunteered to fight in Spain because when Mussolini invaded Ethiopia in 1935 “there wasn’t a hell of a lot I could do about it.” Spain was the first chance to fight back, and Al and his African-American comrades knew when to step up.

The Lincoln Brigade was the first racially integrated military unit in American history. Even during World War II, black soldiers had to serve in segregated units. Yet in Spain black and white fought shoulder to shoulder. The Lincolns were aware at the time that they were making history, and were proud of it.

Oliver Law was a labor organizer from Chicago who as commander of the Lincolns became the first African American to command white troops in the history of the American armed forces. Oliver Law was killed in the battle of Brunete, leading his men in an attack up Mosquito Hill, where he lies in an unmarked grave.

Abraham Lewis (r) of the Brigade Commissariat, with Chief of Auto Park Louis Secundy, Dec. 1937 (Tamiment Library, NYU, 15th IB Photo Collection, Photo # 11-1010)

Jimmy Yates survived the war and wrote a wonderful memoir, From Mississippi to Madrid. We are fortunate to have him on film talking about his experiences in Spain, in this clip from Souls without Borders: “Spain was the first time as a black man I felt a free man.”

Eighty or 90 women volunteered with the Lincolns, mostly in the medical corps, including Salaria Kea, a nurse from Akron, Ohio. Salaria had a passion for medicine from a young age yet was refused admission at three nursing schools in Ohio because of her race before she finally was accepted to the Harlem Hospital Training School in New York, where she graduated in 1934. She experienced discrimination when she volunteered for the Red Cross and enlisted for Spain in 1937.

In Spain the Lincolns fought the good fight yet they lost. It was there that they learned, in the words of Albert Camus, “that one can be right and yet be beaten, that force can defeat spirit, that there are times when courage is not its own reward.” Nearly a third of the American volunteers, black and white, Jewish and Christian, Latino and Asian, lie buried in the Spanish earth. When the survivors came home they were greeted as heroes by the Left and as common criminals by the government.

When the United States entered World War II most of the able-bodied vets volunteered for service. Despite the fact that they were virtually the only Americans with direct combat experience they had difficulty being sent overseas. The African Americans, who fought side by side with their white comrades in Spain, were forced to serve in segregated units and were not assigned combat roles until the very end of the war. After the war, they faced a double discrimination: for their skin color (“back to the bottom,” as Salaria Kea put it), and for their politics. For they had landed in Jim Crow America, a country caught in the throes of the anti-Communist hysteria of the McCarthy era.

It wasn’t until the Civil Rights movement in the 1960s that things began to change. We have a picture of Paul Robeson with Julian Bond as a child: passing the torch, handing on the passion for justice from one generation to the next.

The vets didn’t sit out this good fight either. Del Berg recently recalled that his proudest moment since Spain was “When I was elected vice president of the local NAACP.” Milt Wolff worked for the Civil Rights Congress, touring the south with an African American folk singer in defense of black prisoners. Jack Penrose joined sit-in strikers to integrate lunch counters in Gainesville, Florida. And Abe Osheroff spent the Freedom Summer building a community center in a rural black community in Holmes County, Mississippi, where he lived with activist Hartman Turnbow. Veteran Robert Klonsky organized a fundraiser for the Southern Christian Leadership Council, whose first president was Martin Luther King.

And so we come full circle. Today we are presenting the ALBA/Puffin Award for Human Rights Activism to Bryan Stevenson because in his own striving for economic and racial justice he carries the spirit of the Abraham Lincoln Brigade into the 21st century. I believe that Stevenson expresses it best, when he quotes Martin Luther King: “the moral arc of the universe is long but it bends toward justice.”

Tony Geist, longtime ALBA Board member and Chair of the Spanish Department at the University of Washington, presented this talk at the 2014 reunion.

I wrote about Homer Chase, my friend, who fought as a machine gunner in the Lincoln Brigade under Joe Bianca.(Two Communist Brothers from Washington NH. and Their Fight Against Fascism)

Bravest man I ever met.

Don Forbes

[…] Lin, de xeito casual esta mesma semana, unha acendida resposta de Rafael Narbona a Pérez Reverte por mor dunhas declaracións deste último sobre o papel das Brigadas Internacionais na Guerra Civil española. Tamén casualmente dei na rede cun apuntamento en Letters of Note no que se incorporaba unha carta de Canute Frankson, un mecánico xamaicano que decide abandonar Detroit, a cidade na que vivía, para alistarse na Brigada Abraham Lincoln que actuou na Guerra Civil Española. Non foi o seu, abofé, o único caso. […]

[…] Lin, de xeito casual esta mesma semana, unha acendida resposta de Rafael Narbona a Pérez Reverte por mor dunhas declaracións deste último sobre o papel das Brigadas Internacionais na Guerra Civil española. Tamén casualmente dei na rede cun apuntamento en Letters of Note no que se incorporaba unha carta de Canute Frankson, un mecánico xamaicano que decide abandonar Detroit, a cidade na que vivía, para alistarse na Brigada Abraham Lincoln que actuou na Guerra Civil Española. Non foi o seu, abofé, o único caso. […]

Bobby Sands 1954 -1981 said this,

“The spirit of freedom will never die”

My father Jefferson T. Wideman was one of the 90 African Americans who fought in Spain, and was a member of the Lincoln Bridage