Book Review: Teenagers fighting Franco

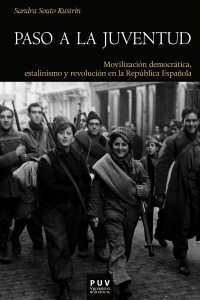

Paso a la juventud. Movilización democrática, estalinismo y revolución en la República Española. By Sandra Souto Kustrín. (Valencia: Publicacions de la Universitat de València, 2013.)

Editor’s Note: Although the book under review is only available in Spanish, we believe the themes discussed will be of interest to our readers.

In the violent conflicts of twentieth century Europe, vast sectors of society mobilized in the fight to determine the continent’s future social and political order. New opportunities—blown wide open by the Great War of 1914-18—that promised political, social and cultural emancipation were met head on with attempts at closing them down by the old elites of imperial Europe and their rigidly hierarchical social order. Within this struggle to make sense of change and determine the future, political leaders initiated an unprecedented mobilization of young people, who were quite literally that future. In an outstanding contribution to our understanding of those struggles, Sandra Souto examines youth mobilization in the Spanish Republic during the civil war. Far from “youth running wild” in the ruins of empire, Souto reveals young people to be decisive, determined protagonists in this pivotal battle for modernity.

In the violent conflicts of twentieth century Europe, vast sectors of society mobilized in the fight to determine the continent’s future social and political order. New opportunities—blown wide open by the Great War of 1914-18—that promised political, social and cultural emancipation were met head on with attempts at closing them down by the old elites of imperial Europe and their rigidly hierarchical social order. Within this struggle to make sense of change and determine the future, political leaders initiated an unprecedented mobilization of young people, who were quite literally that future. In an outstanding contribution to our understanding of those struggles, Sandra Souto examines youth mobilization in the Spanish Republic during the civil war. Far from “youth running wild” in the ruins of empire, Souto reveals young people to be decisive, determined protagonists in this pivotal battle for modernity.

With the Spanish Civil War central to understanding those broader currents of violence that stretched across Europe, Souto provides a welcome analysis of those transnational complexities, firmly locating the forging of Spanish youth politics within broader political and cultural milieus of this world in crisis. The appeal to the young was, as Souto explains, “the last card played by all…in the encounter between fascism and anti-fascism,” as all sides realized the adage that who has the youth, has the future.

In Spain paso a la juventud [make way for the youth] formed part of an ideological mobilization behind the Republic. Souto demonstrates that young people became fundamental to the Republican war effort, laying down their lives as a political vanguard in the first weeks and months after the coup and performing a crucial role in the mobilization of the home front toward cultural and material production. In that sense, youth politics played a key role in the mass support and political culture of the wartime Republic and in the creation of a new national and political fabric. Of particular interest is Souto’s original analysis of the extent to which youth organizations mobilized young women and children, offering a theoretical and empirical challenge to the established tendency to understand youth politics in a masculine interpretative paradigm.

Souto underscores the civil war as a landscape of possibility for young people and illustrates how they were able to navigate the war as an event by tactically manoeuvring within the political spaces opened up after the war began. The confrontation between war and revolution permeates those negotiations throughout, and although the theoretical radicalization and fragmentation of youth politics during the Republic is well explored, Souto contributes significantly to understanding the practical impact of this radicalization. Souto makes clear that translating political ideas onto the landscape of the wartime Republic engendered political infighting and painful self analysis. Mass mobilization challenged ideological coherence, and the demands of war conflicted with revolutionary dreams.

The final chapter of the book recounts the searing experience of defeat. The Casado coup against the Republic in early 1939–triggering the final implosion of Republican resistance–gave brutal form to fractures and animosities in a panicked climate over what the future would hold. The dismemberment of that open, progressive future was embodied in the huge physical and psychological destruction unleashed by Francoism. Souto conveys the sheer scale of the destruction wrought on Spain’s youth: the number of young people killed in combat or extra-judicially murdered, imprisoned, “disappeared,” and exiled stands as a visible incarnation of the destruction of the future.

Souto admirably combines theoretical material with extensive and rich documentation, much of it new or underused and encompassing a broad array of Spanish and international material. Despite the fundamentally important role of youth organization and mobilization in the breakdown of the Spanish Republic and in the violent struggles of European politics, the conventional wisdom of much of the existing historiography remains simplified. Souto provides the framework for a more acute analysis that charts the evolution and development of youth both as a social group in the Spanish Republic and as a historically constructed concept.

The book stands as a welcome addition to our understanding of the central role youth politics played in the polarization of politics and society in the maelstrom of the 1930s. It is impeccably researched, brought to life by the individual stories and by Souto’s readable style and acute analysis. Exploring new avenues of investigation, Souto has contributed not only to our understanding of the Spanish Civil War, but more widely to Europe’s twentieth century and the experiences of the young within it.

Richard Ryan is a PhD student at Royal Holloway, University of London where he also teaches courses on twentieth century Spain.

[…] called “the volunteer”. I searched it up and confirmed it as a article made by VALB(https://albavolunteer.org/2013/12/book-review-teenagers-against-franco-communist-youth-in-the-spa…). Raplh said the Volunteer really brought back memories of his time of war in Spain and World War 2 […]