Book Review: Anticlerical violence in Spain

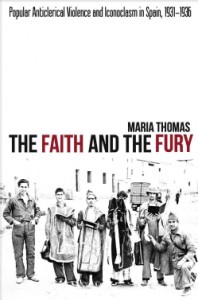

The Faith and the Fury: Popular Anticlerical Violence and Iconoclasm in Spain, 1931-1936. By Maria Thomas. (Brighton: Cañada Blanch Centre for Contemporary Spanish Studies/Sussex Academic Press, 2013.)

The Faith and the Fury: Popular Anticlerical Violence and Iconoclasm in Spain, 1931-1936. By Maria Thomas. (Brighton: Cañada Blanch Centre for Contemporary Spanish Studies/Sussex Academic Press, 2013.)

When the Spanish Republic came to power in 1931, Catholicism was the nation’s only religion and was clearly identified with political conservatism and social order. Despite the liberal revolutions of the nineteenth century, the confessional state had remained intact. Spain remained the quintessential example of a country with a single dominant religion, a religion led and followed by the people, bishops, religious and ordinary Catholics, who believed that the total preservation of the social order was an inalienable right, given the historical and cultural fusion of order and religion throughout Spain’s history.

Even in the face of the omnipotent Church, a counter tradition of criticism, hostility and opposition nevertheless emerged. Already active in the 19th century, an anticlerical liberal and left-intellectual bourgeoisie agitated to reduce the power of the clergy in the state and society. During the 20th century Spanish anticlericalism entered a new phase in which radical militants joined with workers. First in Barcelona, and later in other Spanish cities, an anticlerical movement took hold in which republicans and organized labor (socialist or anarchist) collaborated. This alliance constituted a strike against both the Church and the traditional oligarchy, and established networks of cultural centers, newspapers, secular schools and other forms of popular culture.

The Church pushed back against these winds of change; of modernization and secularization. And it constructed a formidable wall of resistance against those groups that challenged Church doctrine or the way of the life that the Church promoted and protected. These are the tensions that forged the history of constant and intransigent resentment between clericalism and anticlericalism, between order and change, reaction and revolution. The conflict between these systems of belief and ways of life grew increasingly acrimonious during the Spanish Republic, and of course, turned murderous during the Spanish Civil War, ending with the violent and definitive triumph of clericalism in 1939.

The Church and the anticlerical movements willingly joined the battle on key issues related to the organization of society and the State that were fought on Spanish soil between 1936-1939. Religion would prove most helpful to the cause of Franco and the Nationalists. Violent anticlericalism that began with the military uprising did not provide any benefit to the Republican cause. Published reports and photographs of the destruction of churches and the murder of clergy, often illustrated with macabre photographs, were published widely in Spain and beyond the Pyrenees. These images became quintessential symbols of “Red Terror.”

The civil war thus took on a religious dimension that condemned anticlericalism as a negative ideology and practice, rather than as an important phenomenon of cultural history, with its particular vision of truth, society and human freedom. All supporters of the defeated Republic were forced to become defensive on the subject of religion, even though they continued to remember and value the important Republican fight for education, for the creation of a secular bureaucracy, and for making religious orders subject to the legislation of civil associations. The meaning and memory of these Republicans initiatives were overwhelmed by anticlerical violence that left 6,832 clergy killed.

In her book, The Faith and The Fury, Maria Thomas addresses all these issues. Thomas first reviews, from the perspective of cultural history, the process of anticlerical identity construction before 1931. In the second chapter, the book examines the gap between these two conflicting cultural worlds that widened with the proclamation of the Second Republic and ensnared a large number of Spaniards who had felt hitherto indifferent to the conflicts raging between Catholics and their adversaries. Above all, Thomas’s research focuses on this drama’s main actors because she identifies–as George Rudé did in his studies on the importance of crowds in history–the flesh and blood characters who, from their varied vantage points and ideologies, formed part of the social mobilization of the Civil War period.

The first conclusion Maria Thomas offers is that “rural and urban male workers were the main agents of the wave of anticlerical violence and iconoclasm which began in July 1936.” Thomas shows that the participation of middle-class sectors and people not affiliated with political organizations demonstrate that “anticlericalism was being used as one instrument with which to configure a new social structure.”

Franco’s military uprising finally resolved the conflict between the Church and Republican projects for secularization. Maria Thomas examines how history has cast this divided Spain into two camps, one for the defense of the Church and the other identified by its hostility to religion. Although the empirical analysis in Thomas’s study is focused on the provinces of Madrid and Almeria, thus highlighting the different behavior between urban and rural sectors, Maria Thomas never fails to provide a broader analysis, to use a specific event to draw more general conclusions, or to showcase her detailed knowledge of the most recent historiography of the Spanish Civil War.

Through a combination of primary and secondary sources, analysis and interpretation, The Faith and the Fury stands as an important reference book to understand the devastating effects of the massacre of clergy and the destruction of the sacred, “a complex and changing phenomenon which encompassed a highly heterogeneous collection of social actors.”

Julián Casanova is Professor of Contemporary History, Universidad de Zaragoza. He is the author of numerous studies on Spanish Anarchism and the Franco regime. He’s also a columnist for El País.