US cinema and the Popular Front: Spain as common cause

Joris Ivens and Ernest Hemingway with Ludwig Renn, commander of the Thälmann Battalion. Photo Bundesarchiv.

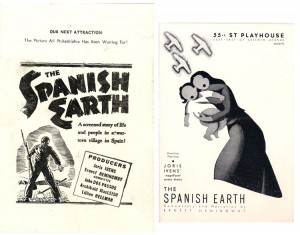

On July 25, 1937, the New York Times’ John T. McManus interviewed Joris Ivens, a young Dutch movie director who had just arrived in the United States. What sparked the interview was the premiere of The Spanish Earth, a documentary about the Spanish Civil War financed by a handful of American intellectuals that included John Dos Passos, Dorothy Parker, Lillian Hellman, and Dashiell Hammett. The film, Ivens later explained, had three main objectives: direct political and ideological action (changing the U.S. policy of neutrality toward Spain); direct material action (raising money for ambulances); and leaving a testimony for the future.

The interview took place at the Rockefeller Center’s Luncheon Club, towering more than 60 stories over mid-town New York. “Below us,” McManus wrote

… lay Central Park, stretching two or three miles to the north. Mr. Ivens walked to the parapet and indicated 110th Street. “From the Telefónica (Madrid’s eighteen-story skyscraper), the Fascist line in University City appears right up there,” he pointed. His arm swung in an arc, as if preparing to point out something else. It found a distant Broadway street car. “There, over there,” he said, “the street car. Five minutes to the front line.”

Ivens’s brilliant use of the familiar New York landscape to explain graphically the situation in Madrid was as simple as it was effective. In fact, it was a frequent strategy among American supporters of the Spanish Republic who tried to raise awareness of the Civil War among their fellow citizens. They were convinced it was necessary to show the close ties between the plight of the Spanish people and America’s struggle to overcome the Great Depression.

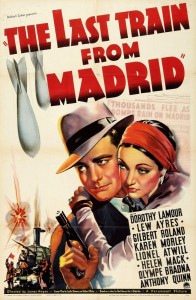

The image of Spain that had dominated American travel literature and Hollywood film was rife with stereotypes: sun, fiestas, gypsies and bullfights. But political developments in the 1930s were so far reaching that even the most superficial of Hollywood movies registered their impact. The Spanish Civil War was the backdrop to two romantic dramas from 1937, for example: both The Last Train from Madrid (James P. Hogan, video) and Love under Fire (George Marshall) were set during the evacuation of Madrid. A year later, when the WPA’s Federal Dance Project staged Guns and Castanets, an adaptation of Prosper Merimée’s Carmen (first published in 1845), it was again set in Civil War Spain. The novel’s female protagonist is a gypsy dancer in a café, while Don José is a Republican fighter pilot and Escamillo, the bullfighter, flies planes for the Francoists.

The image of Spain that had dominated American travel literature and Hollywood film was rife with stereotypes: sun, fiestas, gypsies and bullfights. But political developments in the 1930s were so far reaching that even the most superficial of Hollywood movies registered their impact. The Spanish Civil War was the backdrop to two romantic dramas from 1937, for example: both The Last Train from Madrid (James P. Hogan, video) and Love under Fire (George Marshall) were set during the evacuation of Madrid. A year later, when the WPA’s Federal Dance Project staged Guns and Castanets, an adaptation of Prosper Merimée’s Carmen (first published in 1845), it was again set in Civil War Spain. The novel’s female protagonist is a gypsy dancer in a café, while Don José is a Republican fighter pilot and Escamillo, the bullfighter, flies planes for the Francoists.

We cannot understand the presence of the Spanish Civil War in U.S. media without appreciating the impact on the American left of the Popular Front movement—the broad coalition against fascism that was ratified by the Third Communist International at their Seventh Congress in 1935. For the next 10 years, capitalism was no longer public enemy number one, while Socialists and Communists postponed their revolutionary aspirations, joining forces with liberals, pacifists and progressives to quell the global rise of fascism.

In the United States, Popular Front politics developed two important lines of action, one domestic and one international. Internationally, Popular Front organizations fought fascism through political activism, humanitarian action, and the recruitment of volunteers for the frontlines of struggle. After Mussolini’s invasion of Abyssinia, Spain became the central battle field, and the Abraham Lincoln Brigade was the most salient example of the internationalist initiatives undertaken as part of the U.S. Popular Front.

Response to the superficial, romanticized Hollywood versions of the Spanish Civil War, U.S. filmmakers associated with the Film Front—specifically the production company Frontier Films—produced two outstanding political documentaries with a humanitarian theme: Heart of Spain (Herbert Kline and Geza Karpathi, 1937) and Return to Life (Henri Cartier-Bresson and Herbert Kline, 1938). Both focus on medical help for victims of the war. Heart of Spain featured the innovative mobile blood transfusion units created by the Canadian physician Norman Bethune and led by Dr. Edward Barsky from New York. Return to Life dealt with the revalidation of wounded International Brigaders in Republican hospitals on the Mediterranean coast. By showcasing the mutual support and sympathy between the Lincoln volunteers who risked their lives to fight fascism on Spanish soil and the Spanish people who in turn gave their blood to save the lives of the wounded, both films articulate a clear notion of international solidarity based on social and political commitment

The second line of Popular Front action was domestic and focused on the efforts to overcome the devastating effects of the Great Depression. The Popular Front helped create collaborative networks with New Deal government projects like the Works Progress Administration, linking the need for progress and recovery with the idea of social justice. Popular Front organizations united liberals and radicals, but they also brought together politicians with artists and intellectuals—the so-called Cultural Front. The first real Popular-Front political adventure in California, the novelist Upton Sinclair’s 1934 EPIC campaign (End Poverty In California), was a failure. Sinclair lost the race for governor but the campaign contributed to the success of the New Dealer Culbert Olson, who landed a seat in the state senate and became governor in 1938. The Cultural Front also helped create wide popular support for Roosevelt’s three Rs (Relief, Recovery, Reform) by producing radio documentaries like Triple-A Plowed, books like You Have Seen their Faces, or movies like The Plow that Broke the Plains (video).

Filmmakers who supported the Loyalist cause in Spain managed to combine what they had earned over the preceding decade of avant-garde experimentation with the great momentum of the new American documentary, embodied by figures such as Paul Strand, Dorothea Lange, and Pare Lorentz. Ivens’s The Spanish Earth (1937, video)—shot in Spain by a Dutch director with funding from American artists and intellectuals—showcased the Popular Front’s international dimension, but it also paid close attention to the immediate, domestic concerns of the American public.

Filmmakers who supported the Loyalist cause in Spain managed to combine what they had earned over the preceding decade of avant-garde experimentation with the great momentum of the new American documentary, embodied by figures such as Paul Strand, Dorothea Lange, and Pare Lorentz. Ivens’s The Spanish Earth (1937, video)—shot in Spain by a Dutch director with funding from American artists and intellectuals—showcased the Popular Front’s international dimension, but it also paid close attention to the immediate, domestic concerns of the American public.

The Spanish Earth tells the story of the people of Fuentidueña de Tajo, a small town on the main road leading from Madrid to Valencia, whose strategic location makes it a vital support point for the troops at the Jarama front. The film underscores the urgent need to irrigate the recently collectivized lands, which until then had been left fallow by absentee landowners. In scenes that echoed Hollywood’s Our Daily Bread (dir. King Vidor, 1934), Ivens’s villagers’ successful irrigation project brings life to the Spanish earth and allows the farmers to produce food for the town and the front. Ivens said he did not set out to make a film about ideologies but about men and women who work and fight for “melons, tomatoes, onions.” For an American audience, the connection with the rural crisis in the United States was impossible to miss. The message was clear: the struggle was a shared one.

Sonia García López teaches Film and Television Studies at the Universidad Carlos III in Madrid. Her book Spain is US: La Guerra Civil Española en el cine del “Popular Front” (1936-1939) came out earlier this year with the Universitat de València.

I have found this article most interesting, and as a researcher on the American propaganda film “Spain in exile” (1946), produced by Paul Falkenberg and directed by Guillermo Zúñiga for the Joint Antifascist Committee (in collaboration with the Unitarian Service Committee) I would like to kindly ask the experts and veterans gathered on this blogspot, in order to know if any of you could provide me with any information related to the making of and production of this film.

[…] publicado en The Volunteer: “US Cinema and the Popular Front: Spain as a common cause”, 14 de septiembre de […]