Tourism in Franco’s Spain

Among many other Spanish Civil War commemorations this year, it may be interesting to note that July 2013 marks the 75th anniversary of one of the conflict’s most bizarre episodes. In December 2005, Professor Sandie Holguín of the University of Oklahoma published a piece of research in the American Historical Review, was based on documents discovered in the Mandeville Special Collections Library in San Diego. They included brochures published by the National Spanish State Tourist Board which Franco had felt confident enough to establish early in 1938.

Among many other Spanish Civil War commemorations this year, it may be interesting to note that July 2013 marks the 75th anniversary of one of the conflict’s most bizarre episodes. In December 2005, Professor Sandie Holguín of the University of Oklahoma published a piece of research in the American Historical Review, was based on documents discovered in the Mandeville Special Collections Library in San Diego. They included brochures published by the National Spanish State Tourist Board which Franco had felt confident enough to establish early in 1938.

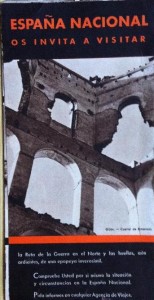

One brochure features a map of Northern Spain and a row of photographs depicting soldiers of Franco’s army, the bombed ruins of Spanish towns and, incongruously, the mountains and beaches of the Cantabrian coast. It begins:

National Spain invites you to visit the War Route of the North (San Sebastián, Bilbao, Santander, Gijón, Oviedo, and the Iron Ring). See history in the making among Spanish scenery of unsurpassed beauty.

National Spain invites you to visit the War Route of the North (San Sebastián, Bilbao, Santander, Gijón, Oviedo, and the Iron Ring). See history in the making among Spanish scenery of unsurpassed beauty.

The brochures were circulated widely by travel agencies across Europe and there were soon bookings pouring in to secure places on the tours. Franco purchased school buses from the Chrysler Corporation, trained a team of guides and, on July 1, 1938, while the war raged, and before the Ebro campaign had begun, the first of the tours took place. The cost was £8 for a nine-day tour, including three meals a day, accommodation in first-class hotels and incidental expenses.

Franco used the tours as a straightforward propaganda tool, to tell the Nationalists’ version of events, and also as a visible sign to the outside world that he was winning the war. In addition, the scripts used by guides helped him to redefine the identity of Spain that fit the images the fascists wanted to portray—particularly the image of the Nationalists’ insurrection as a “Holy Crusade.”

Franco used the tours as a straightforward propaganda tool, to tell the Nationalists’ version of events, and also as a visible sign to the outside world that he was winning the war. In addition, the scripts used by guides helped him to redefine the identity of Spain that fit the images the fascists wanted to portray—particularly the image of the Nationalists’ insurrection as a “Holy Crusade.”

Holguín tells us: “The tours ran every other day from July through October, and the following year the tour season began in May.” By December 1938, a second route had been introduced, in Andalucía. At the end of the war, two more routes were added, one in Aragón, the other in Madrid. Tourists arrived in large numbers—from Britain, Italy, Portugal, France, Germany, from Australia. It is thought that there were around 42 tours in 1938 and 88 tours each year between 1939 and 1945. Estimates of participants vary between 6,670 and 20,010.

Sandie’s research paper can be downloaded in its entirety here.

I came across the report two years ago and was fascinated by it. It struck me that the tale needed some wider circulation and also that it would make an unusual subject for a historical novel. And therefore The Assassin’s Mark was born. It’s a Christie-esque thriller set on one of the tour buses in September 1938, during the same week in which the Sudeten Crisis was developing. British journalist, Jack Telford, covering the journey on behalf of Reynold’s News, the weekly paper of the Co-operative Party, finds himself traveling with an assortment of unsympathetic fellow-travelers.

Apart from the fictional aspects, the novel gave me an opportunity to describe the struggle of the Republican armies and the way in which the Nationalists managed, for so many years, to conceal the truth of war crimes like the bombing of Guernica. It wasn’t easy. We know much about the conduct of the Civil War now but, as an author, you can only tell the story from the perspectives of the period in which it’s set.

Dave McCall writes historical novels under the pen name David Ebsworth. The Assassin’s Mark was published in March 2013.