Review: War Comes to Andalusia

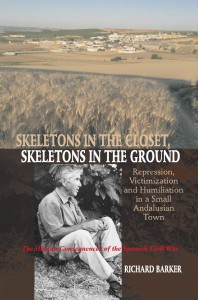

Skeletons in the Closet, Skeletons in the Ground: Repression, Victimization and Humiliation in a Small Andalusian Town. By Richard Barker. (London: Sussex Academic Press, 2012).

In recent years, Spain has been reshaping its relationship with its violent past. Episodes from the Civil War and the Franco dictatorship whose mention was long taboo have come to the forefront of sociopolitical debate. The desire to forget has become the desire to remember—witness the tireless work of the Association for the Recuperation of Historical Memory, active since 2000, and the opening of mass graves around the country, the Law for Historical Memory passed in 2007, the search for the grave of Federico García Lorca, and the legal case against judge Baltasar Garzón. Books and films about long silenced stories of the defeated have become a crucial vehicle for the recovery of the repressed past. Their aim has been two-fold: to break the silence and to return dignity to the victims.

In recent years, Spain has been reshaping its relationship with its violent past. Episodes from the Civil War and the Franco dictatorship whose mention was long taboo have come to the forefront of sociopolitical debate. The desire to forget has become the desire to remember—witness the tireless work of the Association for the Recuperation of Historical Memory, active since 2000, and the opening of mass graves around the country, the Law for Historical Memory passed in 2007, the search for the grave of Federico García Lorca, and the legal case against judge Baltasar Garzón. Books and films about long silenced stories of the defeated have become a crucial vehicle for the recovery of the repressed past. Their aim has been two-fold: to break the silence and to return dignity to the victims.

Richard Barker’s Skeletons in the Closet, Skeletons in the Ground: Repression, Victimization and Humiliation in a Small Andalusian Town, is an outstanding addition to this growing corpus of historical documentation, examining how the Civil War affected the small Andalusian town, Castilleja del Campo (Seville). Following the paradigm of microhistory, the book is based on an intensive historical investigation of the everyday life of ordinary people in a well-defined, small unit, while aspiring to find answers to larger questions related to social and political changes. Barker’s Castilleja del Campo mirrors the fast and radical changes that impacted Spain before, during, and after the Civil War. He offers a clear and comprehensive vision of this tumultuous time as well as a diverse mosaic of testimonies that, among other things, describe the terror imposed upon Castilleja’s inhabitants during and after the conflict. It is this combination of history and memory, general and particular, that makes the book engaging and enlightening.

Barker underscores the agency of historical actors. A literary critic by training, he blends sociology and oral history, grouping together hundreds of personal accounts. The translations of these testimonies faithfully reproduce colloquialisms and disjointed sentences, reflecting the linguistic peculiarities of the area and help us discern the local population’s knowledge and understanding of historical events as they affected their lives. Some of the testimonies are representative, even typical, of the repression during the war and the marginalization during the dictatorship suffered by the defeated. Recurring episodes include the forced drinking of castor oil or the shaving of women’s hair. Other lesser known stories recall even more vividly the horror of those years, such as the incident told by Barker’s informant Narciso Luque Romero: A firing squad was going to give the coup de grâce to a pregnant woman they had shot moments before, they saw that the baby had been born of the dead woman. They killed the infant right there. The number of testimonies he provides, besides contributing to the verisimilitude of the historical narration, demonstrates Barker’s care for detail. That said, the abundance of testimonies sometimes slows down the pace of the story.

While Barker recorded these testimonies in the 1980s and 1990s, the fact that he did not publish his book for two decades has not made his accomplishment any less relevant. To the contrary, the changed attitude in Spain regarding the memory of the Civil War guarantees that his work has a greater impact now. The book’s appendix discusses the politics of memory developed in Castilleja del Campo since the transition to democracy—that is, attempts to recognize and honor victims of repression—and brings out important points regarding the impact of various endeavors referred to as the recovery of historical memory. While the book does not explicitly address this impact, it shows that giving witnesses a chance to talk about traumatic experiences provides catharsis. Similarly, cultural events organized in the wake of Barker’s book have enriched Castilleja’s cultural life. Barker acknowledges that this process is difficult, but also emphasizes its necessity. “[I]t [is not] my intention that this book be used as a weapon to be thrown in others’ faces,” he writes; “Castilleja del Campo needs to turn the page. If it has still not been able to do so more than 70 years after repression, perhaps it is because that page cannot be turned without being read.”

Carmen Moreno-Nuño teaches at the University of Kentucky. Her research focuses on the cultural representation of the historical memory of the Spanish Civil War and the postwar era in democratic Spain.