Chim in the Spanish Civil War Another Way Of Seeing

“We are only trying to tell a story….We’ve got to tell it now, let the news in, show the hungry face, the broken land, anything so that those who are comfortable may be moved a little.” —Chim

Many photographers covered the Spanish Civil War, both foreign and Spanish, professionals and amateurs, but the Polish-born David Seymour, better known as Chim, made a unique contribution because of the sheer variety of topics and styles he presented. While his friends Robert Capa and Gerda Taro were most at ease in action shots, Chim’s range was much wider. The Spanish Civil War allowed Chim to hone his skills as a reporter. And although he was interested in carefully constructed, well-sequenced reportage that told stories in-depth, many of his single images are striking on their own.

During the thousand days of the Spanish Civil War, Chim traveled across Spain to produce almost 30 stories that were featured primarily in Regards, the left-wing illustrated magazine published in Paris, but also in Vu, Voilà and the evening paper Ce Soir. His pictures were often resold to magazines outside France, such as the Weekly Illustrated and Life, by Maria Eisner of Alliance Photo. Chim—who was born as Dawid Szymin in Warsaw in 1911–had been Special Correspondent for Regards since the spring of 1936. In fact, it was through his intervention that Capa and Taro went to Spain, where she would find her death on the Brunete front and he would shoot the photo of the Falling Soldier that became an international symbol of war photography.

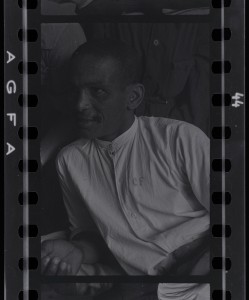

4. A Moroccan prisoner who fought with the “Regulares Indigenas”. Prison barracks near Madrid, October 1936. Photo David Seymour, ICP, Mexican Suitcase.

Contrary to popular belief, it is not true that Chim never went to the front. Although unlike Capa and Taro he tended to avoid images of dead bodies and the wounded, several of his action shots were taken at great risk in the heat of battle. Near Madrid, in October 1936, his images of a firing cannon are drenched in the smoke of combat. Another picture taken at an unidentified location in 1936, shows close-ups of Republican soldiers in combat with a cannon and antiquated guns. Near Oviedo, in February 1937, he took a series of close-up shots of dinamiteros ready to set fire to their charges with a cigarette. In the battle of the Ebro river in 1938), he shot panoramic close-ups of soldiers running and throwing hand grenades in a cinematic style resembling Capa’s, the figures blurred by movement. The photographs were taken close to ground level: the photographer was clearly crouching, and we feel immersed in combat, as if the smoke and dirt of the battle were exploding in our faces.

Chim’s mind was more thoughtful and analytical than Capa’s. His interest included life “behind the scenes,” focusing on the means with which the war was fought and the role of women in the war effort. In the Basque country, he chronicles women at work, replacing the factory workers who had gone to fight. Some are working in missile factories, others are busy in assembly workshops, putting together airplanes sent in parts by the USSR. Others are painting bombs or manufacturing shells in a munitions factory. In February 1937 in Langreo, he photographed women working in the mines: surrounded by towering piles of coal, they are shoveling the fuel into wagons. In his photographs, women invariably emerge as independent and strong, able to sustain the war effort.

The Spanish Civil War was among the first, large-scale modern conflicts where civilians were specifically targeted. Well aware of this, Chim focused on ordinary civilians, giving the magazine reader a sense of how daily life was affected by war. In a number of locations, his photographs cover a range of everyday activities. People sought entertainment to keep their mind off the war: In Barcelona, a crowd cheers a football match at the Club, a soldier and his girlfriend ride a bumper car in an amusement park, girls show off their new swimsuits to soldiers on a beach. Crowds are amassed inside the Cafe Manacor in Gijón (February 1937), and in Minorca, an island off the Catalan coast, people attend the premiere of a play at the Mahon Theater (1938).

Rather than confirming stereotypes, Chim’s photographs unsettled ready-made assumptions. They showed, for instance, how Republicans could be devout Catholics. In one of his most successful and widely published reportages (1937), Basque soldiers attend an outdoor mass at the front in Amorebieta. Similarly, Republican soldiers, who had been previously accused of destroying works of art, work hard to salvage them at the Monastery of the Descalzas (October 1936) or in Madrid’s Palacio de Liria. Life goes on despite the war: in Bermeo, fishermen repair their nets (January-February 1937), and in Minorca, vendors work at a fish market (1938).

Children are often the focus of Chim’s photographs, an interest he would pursue in his famous 1948 UNESCO series Children of Europe. We see kids receiving milk and food, or writing their lessons on the blackboard in a Barcelona public school (October 1936) and playing with a helmet found in the ruins of Gijón (February 1937). In a Barcelona maternity ward, a woman holds her newborn and reads the Vanguardia newspaper; another writes a letter; and nurses hold four newborn babies (July 1936).

One of Chim’s talents was his ability to build rapport with individuals from every walk of life. Even in the middle of war, he managed to have people pose for him. Among his portraits of writers, those of Rafael Alberti and Jose Bergamín are similar: in both, the poet’s face is bisected, leaving half of it in the shadow (much like in the Moholy-Nagy portraits that Chim had admired while studying in Leipzig). His portrait of Dolores Ibárruri, La Pasionaria, April-June 1936, reflects her charismatic and passionate personality tinged with tragedy. Some of his best portraits are the series of Republican soldiers from Asturias (January 1937), posed against the background of the sky. In the faces of Basque soldiers at Amorebieta, optimism and bravery shine through.

Traveling to Das, in the Catalan Pyrenees, Chim went into the coal mines with elderly peasants who had replaced the young miners fighting at the front. Joining the miners for their outdoor picnic, he shot several portraits. “A ray of sun comes out. We take advantage of it and they line up against the shed, sheltered from the north,” wrote the reporter. “There is a nice old guy who is moved to know that his portrait will be published in the paper, just like that of a brave revolutionary fighter. He cannot stop shaking our hands. He has tears in his eyes.”

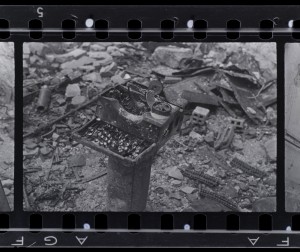

Destroyed typewriter after bombing. Gijón, Asturias. January, 1937. Photo David Seymour, ICP, Mexican Suitcase.

Some of Chim’s most extraordinary portraits are those of the Regulares indígenas, Moroccan soldiers that Franco had induced to fight for him and who were killed by the thousands. The pictures were taken in prison barracks near Madrid in October 1936. Sober and moving, the images pass no judgment but rather have a quality of tenderness and mystery. Looking the “other” in the eye, Chim photographed them with humanity and the same respect he showed the Republicans.

Chim, ever attentive to details, also managed to compose eloquent still-lives, powerful symbols of war, such as his photographs of a crushed typewriter on a pedestal and of a table laden with bullets in the ruins of Gijón.

Even while covering a war, Chim had an uncanny capacity for slowing down, for reflection in the middle of chaos. Twenty years later, in the Suez war, his friend Bill Bradlee described him as “a lone figure, completely calm, clicking away. It was almost in slow motion. He looked at the scene and raised his camera and took [his] pictures very slowly.” It was while covering that war, on November 10, 1956, that Chim was shot to death.

A photography historian and poet, Carole Naggar has recently authored the lead essay for a book on Christer Stromholm, Postscriptum (2012), a text for Chim’s catalogue at the International Center for Photography (2013) and a book, Chim’s Children of War (2013). She is working on Chim’s biography.

The exhibition of Chim’s work, We Went Back: Photographs of Europe 1933-1956 , will be shown at ICP through May 5, 2013. The catalogue is published by Prestel. (Buy it from Powell’s and support ALBA.)