Veterans Day at UW: The ALB and the “military family”

The memorial to the volunteers of the Abraham Lincoln Brigade at the University of Washington, Seattle. Photo and flowers from Glennys Young.

Is there a military family of the Spanish Civil War, and of the International Brigades in particular? Until November 11, 2012, I had never asked myself, or anyone else, that question. And the odds were against my doing so, not the least because “military family” and “Spanish Civil War” are words that are not paired together. Nor am I sure I ever would have done so, had I not attended the Veterans’ Day commemoration at the University of Washington. In his short speech on a somehow appropriately grey and rainy Seattle day, on a campus laced with fall leaves, the President of the University, at the request of ALBA board member Anthony Geist and other UW faculty members, acknowledged the monument to the Lincoln Brigade on the campus, as well as the eleven University of Washington students who served in it. The President’s speech—which also paid homage to UW students who had fought in other wars and to the other veterans’ monuments on campus—was just one of several events that prompted me to reflect on a question I never expected to find myself pondering.

It was the keynote speech that day, by my History Department colleague Robert Stacey (now Acting Dean of the College of Arts and Sciences) that reminded me of what it can mean to be part of a military family. Until six years ago, he said, he never would have considered his to have been such a family. It was at that time that his son, Sargent Will Stacey, enlisted in the United States Marines. Listening to Bob speak, I was thinking back to that time, when he and his wife Robin (also a History Department colleague) told me and other faculty that Will—whom I had met when he was a little boy—was enlisting. Will was killed by an improvised explosive device on January 31, 2012 while on foot patrol in Afghanistan. He was due to come home for good a month later. It was his son’s heroic service, and his ultimate sacrifice that, his father said, had earned him the right to speak to members of other military families, and the public, that fall day at the Veterans’ Day ceremony.

I might never have connected the words “military family” to the Spanish Civil War, and the Lincoln Brigades in particular, had I not decided to pay tribute to the UW veterans of that war by laying some flowers in front of the monument. I bought some white alstroemeria—which, I recalled, were a hearty breed—at a nearby grocery store, and then headed to the monument, which faces the student union building. Satisfied that the flowers were placed in a respectful way, I started walking back to my office. The campus was almost deserted. On the way to place the flowers, though, I had noticed a man standing in the middle of the plaza in front of the student union building. He looked somewhat familiar, but I couldn’t place him. As I walked past the building, he asked me, in a friendly way, what I was up to. I told him what I had just done—that is, I explained that the monument before which I had placed the flowers honored the memory, and the service, of the volunteers in the Lincoln Brigade during the Spanish Civil War. “Did you have relatives who fought in that war?” he asked me as we walked up the path in the drizzle. In the moment, I took the question in a literal sense, clarifying that I had no family members who fought in the war. At one point or another, he clarified for me why he seemed familiar: I had “taught him Russian history,” as he put it, a number of years earlier when he was an undergraduate at UW.

Most likely, it was when I was back in my office that afternoon, transcribing an interview, that somewhere in my consciousness the idea of a “military family of the Spanish Civil War” began to percolate. The interview I was transcribing was one that I had been privileged to be given with Marina Coto Zapico, whose mother, Mercedes Coto Zapico, was evacuated from Spain to the USSR in 1937. Mercedes was eleven years old at the time. I had interviewed Marina on September 30, 2012, the day after the Centro Español de Moscú—an organization created in 1966 by the Communist Party of the Soviet Union and the PCE—had held a grand fiesta to commemorate the 75th anniversary of the evacuation of the nearly 3000 Spanish children to the USSR from war-torn Spain. Not long after the war’s violence, among other factors, had catapulted her to the USSR, she was engulfed in the horrors of World War II—or, in official Soviet discourse, the “Great Patriotic War.” Given rudimentary training as a nurse, she assisted at age 15 in surgeries on Russian soldiers, including one whose leg had to be amputated. As I transcribed the interview, the question posed by my former student—now my inadvertent teacher?–had me reflecting upon why it was that I, who not only did not have relatives who fought in the Spanish Civil War but knew no one personally who, earlier that day, had placed flowers to honor the sacrifice of Lincoln Vets.

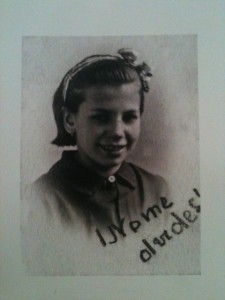

Mercedes Coto Zapico, born in on October 15, 1925, in Carcarosa (Asturias) and catapulted to the USSR as a child refugee in 1937. The handwritten note reads ¡No me olvides! (Don't forget me!). The portrait was on display at the event to commemorate the 75th anniversary of the evacuation of the ninos to the USSR, an event held at the Spanish Center in Moscow, Russia on 29 September 2012.

I formulated in a clear and direct way the question of whether there was such a thing as a “military family of the Spanish Civil War,” and of the International Brigades in particular, as I mulled over writing something for the ALBA blog. That makes sense. Writing, as I like to remind my students, is really an exercise in thinking. No sooner had the question taken final form, then I start asking myself whether I was conceiving of it as more than just a heuristic device, as more than a provocative way of beginning an essay about Veterans’ Day, 2012 at the University of Washington.

I was also hesitant about the question because I think the word “family” is overused, and hence, its meaning devalued. I am old enough to know that even 25 years ago, there weren’t “families” of mutual funds, sports teams, companies, and universities. The rhetorical invocation of the “family” is a recent development in American life, and perhaps in global capitalism as well. Why add to this proliferation? Isn’t speaking of the “military family of the Spanish Civil War’s International Brigades, and Lincoln Brigades in particular” just feeding a tendency I, for one, find rather sickening and hypocritical?

But my former student’s question kept reasserting itself: Did you have relatives who fought for the Lincoln Brigades in the Spanish Civil War? (This is not what he said, but was the gist of his question.) If I didn’t, why did I place the flowers at the UW monument? Of course, people place flowers at monuments, or monumental sites, with some regularity, even if the monuments have no relationship to their relatives in the biological sense of the term. They do so for many reasons, among them being moved by the values, and sometimes the sacrifice, that the monument honors—or, one might say, the story, or stories, it tells. Almost necessarily, these are stories about the past, but ones that, for whom they resonate, speak to the present and future.

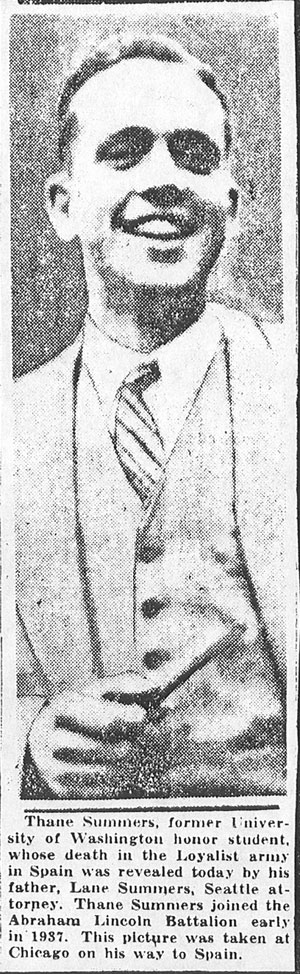

This photo of Thane Summers appeared shortly after his death in Spain in October 1937. Click on the image to read the accompanying article. Courtesy of Joe McArdle, Univ. of Washington, Seattle.

If family means kinship in the sense of shared ideals, then the family of the Spanish Civil War’s International Brigades is one to which I aspire to belong. The ideals that motivated American University of Washington students to join the Lincoln Brigades are those that I deeply admire: selfless commitment to a greater and noble cause, the courage to risk all that one holds dear for one’s principles, and heroism in the face of danger. For me, these are guiding stars, not personal attributes. I have not earned the right to consider myself, or be deemed by others, part of this “military family.” Not only do I not have any relatives, or even close friends, who fought “the last good fight” in the Lincoln Brigades. Nor has my own service, in the broadest sense of the term, embodied those ideals. Yet that does not mean that I have been untouched, or uninfluenced, by them as I have conducted historical research, gotten to “know” Thane Summers, one of the UW students who fought for the Lincoln Brigade and died in Spain, through my UW colleague Mark Jenkins’s masterful play or a UW undergraduate’s prize-winning thesis, seen films, read first-hand accounts, and heard stories about the American (and global) volunteers for the Spanish Republic.

I like to think that I attended the UW veterans’ day ceremony, and placed the flowers at the Lincoln Brigade monument, as a friend of the family. That is, I was doing what friends of families, biological and imagined (but no less real for being so) do: lending assistance as needed. What I provided that day, and with this essay, are small acts of honoring those whose membership—whose true kinship—can never be doubted, and whose service should never be forgotten.

Glennys Young is Professor of History and Director of Graduate Studies at the University of Washington, Seattle, where she also teaches in the Jackson School of International Studies. Her most recent book is The Communist Experience: A Global History through Sources (Oxford University Press, 2011). She is working on the history of Spanish Civil War exiles in the USSR.

A fascinating story.