An apocryphal obituary of a fictional character

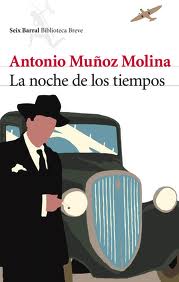

In his massive novel La noche de los tiempos, Antonio Muñoz Molina crafts an unforgettable fictional character named Judith Biely. The daughter of Eastern European Jewish immigrants, Judith grew up in New York, did doctoral work in Spanish Literature at Columbia, and traveled to Spain in the early 1930s to conduct doctoral research. In Madrid she became passionately involved with the protagonist of the novel, a married architect named Ignacio Abel. The culminating scene of La noche de los tiempos takes place a few years later, when Biely and Abel re-encounter each other in the States; Abel has come here without his family fleeing from the chaotic violence unleashed in Madrid by the Spanish Civil War, and almost certainly with the hopes of looking up Judith. Biely, alas, is about to depart as an American volunteer determined to help the Republic.

In his massive novel La noche de los tiempos, Antonio Muñoz Molina crafts an unforgettable fictional character named Judith Biely. The daughter of Eastern European Jewish immigrants, Judith grew up in New York, did doctoral work in Spanish Literature at Columbia, and traveled to Spain in the early 1930s to conduct doctoral research. In Madrid she became passionately involved with the protagonist of the novel, a married architect named Ignacio Abel. The culminating scene of La noche de los tiempos takes place a few years later, when Biely and Abel re-encounter each other in the States; Abel has come here without his family fleeing from the chaotic violence unleashed in Madrid by the Spanish Civil War, and almost certainly with the hopes of looking up Judith. Biely, alas, is about to depart as an American volunteer determined to help the Republic.

When I first read the novel, I was struck by the beautifully constructed character of Judith Biely. And when I completed the novel –which pretty much ends with her heading towards the docks to board the ship that will take her to Spain– I couldn’t stop trying to imagine the rest of her story.

Last Spring, I was invited to present something at a retirement tribute for my great friend and mentor, Sylvia Molloy, who is both a first-rate literary critic and a wonderful writer of fiction. Among her many accomplishments at NYU was the establishment of an MFA program in Creative Writing in Spanish, one of the first of its kind in the US. I decided that to pay homage to Sylvia, I would go out on a limb and try writing a piece of fiction, one that would flesh out the biography of Muñoz Molina’s character. Here’s what came out.

Caveat: The whole thing is fiction, sort of.

*****

Recently, while working with a box of unprocessed documents in the Fredericka Martin papers of the Abraham Lincoln Brigade Archives here at Bobst Library, I came across an unlabelled folder with a curious document. It is typescript, with clippings of other typescripts stapled on to it. Neither the folder nor the document appears in the Tamiment inventory.

**

September 12, 2004

It was a few weeks ago that Judith Biely’s nephew contacted me out of the blue of cyberspace.

[stapled to the typescript, a strip of paper from a printed e-mail:]

“I don’t know if you are the Arlene Paterson who took Spanish classes with my Aunt Judith Biely at Smith in the forties. If you are, please respond. If not, please forgive the intrusion.”

Within minutes of responding in the affirmative, I received a second message:

[another strip, stapled to typescript]

“Aunt Judith has been struggling with severe emphysema for the last ten years, and for the last three years, since she’s been living with me, she’s had a worsening case of dementia. Her breathing recently took a turn for the worse, and when the doctors assured me that she wouldn’t survive more than a few days, I had her transferred to hospice care in the Bronx. She’s actually rallied since she got here, and has been resting comfortably, in and out of consciousness. Yesterday she began blurting out random names. By looking at some old yearbooks she has in my apartment I figured out that some of the names were of former students, you among them.”

Before agreeing to meet in the cafeteria of Calvary the next day, we exchanged a few more messages. He told me how those “few days” predicted by the doctors had turned into several weeks of hospice care, and how Judith was one tough bird. I was taken aback by one exchange in particular; when I offhandedly quipped that Judith must have learned how to survive in Spain, the great nephew corrected me: “You must mean Mexico. She’s never been to Spain.”

***

That night I couldn’t get to sleep as I reminisced about my years as a Spanish major at Smith, and the courses I had taken with Professor Biely both in Northampton and in Cuernavaca, Mexico. It was during the semester in Cuernavaca that I learned from Lini’s daughter the story I wasn’t supposed to know and promised never to tell.

That the love of Judith’s life had been a married Spaniard she had met while conducting thesis research in Madrid. That, some years after the affair, when the Spanish Civil War broke out, and she had begun her career at Smith, he had fled –without his family– from Spain to the US, and she had taken a leave of absence to go to Spain to work as a translator and factotum alongside the nurses and doctors in the US Medical Bureau to Aid Spanish Democracy. That the loquacious and impulsive woman who had left the States for Spain had come back circumspect and subdued; that upon returning to her position at Smith, she lived for a year with students in the Washburn House, which served as the Spanish-speaking house on campus when the war in Spain forced the cancellation of Smith’s program in Madrid; that a few years later, with the help of Lini and Fredericka and other American expats with whom she had worked in Spain, she set up the new Smith program in Cuernavaca, for which we had been the guinea pigs.

I blushed in embarrassment again, sixty years after the fact, remembering that day when, back in Northampton after my semester in Cuernavaca, and while waiting for Professor Biely to show up to class –“Poesía hispanoamericana moderna”, she had walked in on me while I was gossiping with my classmates, with my back to the door, about what I had learned in Cuernavaca: “No estamos supuestas a saber” I had just said, when I realized, from the looks on the faces of my classmates that she had just walked into the room: “¿qué es lo que se supone que no sabéis, Señorita Paterson? Without waiting for a response, she placed a stack of books on the seminar table and recited the first part of a line from the poem we were supposed to memorize for that day: “¡Ay del que pide eurekas al placer o al dolor!” to which the other girls, ever eager to please, and in a credo-like chorus responded “Dos dioses hay, y son Ignorancia y Olvido.”

**

When I arrived the next day at noon to the Calvary Palliative Care Center, Aaron, Judith’s nephew, was already in the cafeteria, eating an egg-salad sandwich and scribbling notes on a legal pad. His blackberry sat and buzzed on the formica table next to the plastic salt and pepper shakers. I introduced myself and immediately lied to him for the first time that day, saying I had already eaten –I never could manage to eat anything in a hospital, palliative or otherwise. An affable and remarkably earnest man, about 55 years old, he thanked me for coming, pointed to the legal pad and said that he was struggling to write an obituary of his aunt. He told me that he was her only living relative; the only and unmarried son of Judith’s younger sister, who had passed some years before. Senior Partner at a big corporate firm specializing in intellectual property cases. He explained that when several years ago, Aunt Judith’s friends in Mexico contacted him saying that they could no longer take care of her, he had brought her to live with him in New York and hired a live-in caretaker, a young woman from Trinidad. Lucinda soon realized –Aaron told me– that even though Judith’s mind seemed to be completely shot, she was a whiz at crossword puzzles, and would blurt out correct answers almost before Lucinda would finish reading the clues. “Pretty much all I’ve ever heard her say are these responses to crossword clues. Add to that the fact that my mother hardly ever talked about her sister, other than to say that she was strange, impulsive, and ‘had taken her fancy Columbia PhD and run off to Mexico for no good reason’”—at this point he gestured toward the legal pad and took a stealthy look at his blackberry, before concluding—“and you’ll understand why I don’t have much to go on for this obituary. It’s a shame too because I have a friend at the Times… I had my secretary google her and it turns out she even wrote a book about some South American poet, but unfortunately it’s in Spanish…”

It was at that point that I decided I didn’t have the mind or the heart or the stomach to help Aaron with his premature obituary; there was just too much he didn’t know and probably wouldn’t understand or believe or want to know; Not just Spain, but the bitter tenure case that dragged on through my junior and senior years, Judith’s real reasons for seeking exile in Mexico from Joe Macarthy’s America. I just told him that I remembered her as a very good professor, serious and genuinely concerned about her students. I recalled that to us students she seemed to have a prodigious memory, especially for poetry. And that when I went on the study-abroad program she led in Cuernavaca, I was surprised at how many people she knew there. Finally, I apologized for not having any other helpful information, and praised him for taking such good care of his aunt. He asked me if I would like to visit Judith in her room; looking at my watch, I declined, inventing an appointment on the other end of the Bronx. As we said goodbye, he mentioned that he was leaving that afternoon to meet with clients in Palo Alto, but would be back in a few days, and would keep me posted.

**

Those were the last words of this impossible obituary of Judith Biely in that folder at ALBA. I have my reasons to suspect that the whole text is apocryphal: that name –“Judith Biely”– doesn’t appear on any of the lists of medical personnel in Spain, or in any library catalog as the author of a book on a South American poet. This is not the first time I’ve alerted the archivists to the existence of suspicious documents in the collection, a tendency I attribute to the establishment of that creative writing program in the Department of Spanish and Portuguese. I think the archivists just humor me, as each time they say that they will place a note in the folder and look into it.

very good