Review: Frank Tinker, Mercenary Ace in the SCW

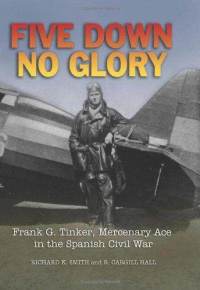

Smith, Richard K. and R. Cargill Hall. Five Down, No Glory: Frank G. Tinker, Mercenary Ace in the Spanish Civil War. Naval Institute Press. Oct. 2011. 377 pp. illus. Timeline. Notes. index. ISBN 978-1-61251-054-5. $36.95. (Buy at Powells and support ALBA.)

Smith, Richard K. and R. Cargill Hall. Five Down, No Glory: Frank G. Tinker, Mercenary Ace in the Spanish Civil War. Naval Institute Press. Oct. 2011. 377 pp. illus. Timeline. Notes. index. ISBN 978-1-61251-054-5. $36.95. (Buy at Powells and support ALBA.)

The reader will note from Five Down, No Glory’s introduction that this study of Arkansan Frank G. Tinker’s life is basically an homage to the memory of its primary biographer, Richard K. Smith (1929-2003). Smith, before his death in 2003, had penned much of the work before R. Cargill Hall’s takeover as secondary author and editor. Hall’s own tribute to Smith entitled: “Richard K. Smith: An Appreciation”, which appeared in the summer 2004 issue of Air Power History, traces his friend’s exciting life as merchant seaman, world traveler, and public historian with a specialization in aviation history.

It has been suggested that Tinker’s life and career are the stuff of legend, a gold mine of material riveting enough to make a Hollywood producer salivate with wild anticipation. Following his bucolic youth in Louisiana and DeWitt, Arkansas, Frank won an appointment to Annapolis (class of 1933). An average student due largely to attitude rather than aptitude, he nevertheless graduated without a commission, a by-product of the economic times. As a result, Tinker gravitated to the Army Air Corp where he earned a second lieutenant’s commission. Soon thereafter Frank returned to his beloved Navy where he finally took his commission as an ensign.

“Salty” Tinker, a nickname carryover from Academy days, piloted scout floatplanes for a time, but following repeated brawls and other code infractions, he resigned his commission. The Arkansan quickly found himself aboard a Standard Oil tanker plying the coastal waters of the United States. Bored and frustrated, 3rd Mate Tinker endured his lot until Spain’s newly declared civil war offered him a rare opportunity.

In Mexico City, Frank signed a contract with the Spanish Embassy to fly for the embattled Republic. He was to receive $1,500 per month with a bonus of $1,000 for every fascist plane shot down, a sum most of which was sent home to his mother on a regular basis.

Tinker arrived in Spain in the first week of January 1937. At first the Republican Air Ministry assigned him to a Breguet XIX bomber outfit. Realizing his potential, however, the Ministry officials quickly transferred him to a newly-formed fighter squadron under the command of Captain Andreas Garcia LaCalle, one of the Republic’s top aces, with eleven victories to his credit.

During Tinker’s seven months in Spain he served in the battles of Jarama and Guadalajara, as well as numerous aerial engagements over the Madrid front. His final eighth victory took place near Brunete on July 18 when he flamed an Italian CR32 pursuit while serving in a Russian squadron, having already downed two of the Nazi Condor Legion’s highly vaunted Messerschmitt BF109 fighters.

As for Frank’s motives for participating in the Spanish Civil War, Smith/Hall write: “confusion had become his friend, and among the chaos that reigned in Spain, he expected to find the key to his destiny,” p. 15 (the old birds-of-feather argument—confused man/confused war). This reviewer can somewhat sympathize with Smith’s initial decision to temporarily shelve his manuscript “Ace of Chaos” (ms. title) aka Five Down, No Glory, in that he seemingly could not settle on the persona of his protagonist: a complex altruist vs. a self-seeking, thrill-seeking daredevil out for lucre and kicks. Perhaps the answer comes much later on page 282 when the biographers introduce Frank previewing his friend Hemingway’s documentary The Spanish Earth in Paris. “Tinker who had rejected ‘the cause’ and its vociferous adherents who ‘had politics’ (an undisguised reference to Ernest Hemingway’s short story Night Before Battle in which the U.S. volunteer pilots are somewhat cynically portrayed) appeared to buy the message. Just to see the picture is to get a better idea of what is going on in Spain than could be gotten by reading reams of literature.” Thus, in the prose of the biographers The Spanish Earth documentary served as a powerful catalyst for everything Frank had witnessed, experienced, and considered in the course of his seven-month tour.

During the Brunete campaign many of Tinker’s old Russian comrades were rotated home. With so few veteran combat flyers to lead the inexperienced Soviet replacements, Frank agreed to command a squadron. But the strain of daytime bomber escort duty and nocturnal enemy raids on his airstrip took a toll. One evening, after a day of missions totaling more than five hours of flying, he submitted his resignation and returned to the States. Upon his arrival in New York City, Tinker’s passport was confiscated by the State Department.

A virtual prisoner in his own country, Tinker returned to Arkansas and wrote a wartime memoir entitled Some Still Live, which was subsequently published in the U.S., England, and Sweden. Selections of his book were serialized in The Saturday Evening Post. With this testament behind him, Frank grew bored and wanted to return to Spain. His way was blocked, however, because of his earlier violation of America’s neutrality laws. He briefly considered a stint with the Flying Tigers in China, but instead succumbed to depression and alcoholism. On June 13, 1939, he committed suicide.

The Smith/Hall biography succeeds in recounting Tinker’s numerous air battles with German, Italian, and Spanish Nationalist adversaries. Depictions of these dogfights are both vivid and engrossing and are, of course, taken from Tinker’s perspective as sourced from his memoir, papers, personal diary, and flight log currently in the custody of a relative. It also wins in recounting his day-to-day life with fellow Spanish Republican and Russian pilots. Perhaps the biography’s best contribution is its detailed examination of the new aerial tactics introduced in Spain, combat techniques devised largely by the Nationalist air forces.

This reviewer was particularly interested in the Smith/Hall back story in which the reputations of the U.S. infantry volunteers from the Abraham Lincoln, George Washington, British, and Canadian battalions, (not to mention foreign troops attached to other international brigades) come across to the objective reader as collateral damage. These soldiers — not mercenaries — are cast as essentially hindrances to the Republican war effort and, moreover, naïve pawns completely in service to Soviet geopolitical objectives (pp. 76-77, 211, 239, etc.). The so-called favorable “mythos” surrounding these expatriate fighters Smith/Hall attribute to the “agitprop” writings of André Malraux, Muriel Rukeyser, and Ernest Hemingway.

As to the events surrounding Tinker’s demise, Smith/Hall’s conjecture that Frank was accidentally shot in a drunken tussle with fellow inebriates in his motel room in Little Rock’s Hotel Ben McGehee is a bit “fanciful.” What interests this reviewer is the fact that the occupant in an adjoining room testified to hearing the gun’s report, but not the noise from Frank’s revelers prior to the shot. A minor observation: Tinker died on a Tuesday, rather than a weekend, hardly a day for a down-home shindig. This reviewer’s money is on suicide as certified by the town coroner, whose report was subsequently destroyed in a courthouse fire. Finally, a tale emerged during Tinker’s 2009 hometown centennial celebration about Frank being murdered by a love interest after she reputedly learned that he was leaving her for Claire Chennault’s Flying Tigers. Perhaps this scenario might have added real spice to Five Down, No Glory’s finale — especially the gory particulars associated with her subsequent suicide.

There are a few noteworthy errors in the Smith/Hall biography.

- On page 67 the biographers state that Condor Legion Major General Hugo von Sperrle’s chief of staff, Lt. Col. Wolfram Freiherr von Richthofen was the son of Manfred (the Red Baron). In point of fact, Wolfram was the cousin of Manfred and Lothar (brothers). Manfred was Wolfram’s senior by three years.

- On pages 127-128 Smith/Hall refer to Piggott, Arkansas as Hemingway’s first wife’s hometown. In truth, it was his second wife’s hometown, Pauline Pfeiffer (1927-1940). Elizabeth Hadley Richardson (1921-1927) was Papa’s first spouse. Following Tinker’s return to Arkansas Frank wrote Papa on October 8, 1937 asking Hemingway to pen an introduction to his forthcoming wartime memoir Some Still Live (of course this never happened). In the second paragraph of this letter he mentions motoring up to see Pauline in Piggott. (Hemingway Collection, JFK Library) This reviewer has the impression that Tinker visited Pfeiffer several times to assure her that her husband was alright. What would poor Pauline have thought had she known about Martha Gellhorn? Perhaps she would have been a bit less concerned about her spouse’s welfare. Actually, many scholars believe that Pauline already knew of Ernest’s dalliance.

- On page 250 the biographers attribute seven (7) aerial victories to Albert J. (Ajax) Baumler in Spain. However, in footnote 3 in the Epilogue Smith/Hall reverse themselves and correctly award Baumler only four (4) confirmed victories in Spain. The American Fighter Aces Association on its website awards Baumler four (4) confirmed “kills”, one (1) shared “kill” and two (2) probables in the Spanish Civil War. Only Tinker is listed as an ace (also the sole U.S. ace during the entire interwar period with eight (8) confirmed victories. According to the AFAA’s numbers Baumler missed ace status of five “kills” in both Spain and subsequently China by just one “kill” in each theater for a total of eight (8) combined victories. Smith/Hall conclude that only paper pushers and public information people care about aerial victory records (p. 239). This reviewer is confident that the AFAA would be inclined to dispute their position.

Overall, an unremittingly sardonic take on a celebrated Navy alumnus and a compelling foreign war of his choosing in which Frank Tinker distinguished himself, and by so doing, brought honor to his native land. What is beyond dispute is that his tragically short life continues to inspire, titillate, and vex aviation specialists and enthusiasts to this very day.

John Carver Edwards is the author of Airmen Without Portfolio: U.S. Mercenaries in Civil War Spain.