Review: A British nurse in Spain

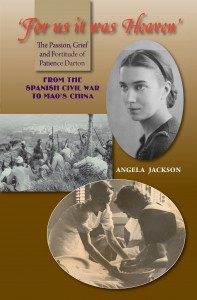

“For us it was Heaven.” The Passion, Grief and Fortitude of Patience Darton, from the Spanish Civil War to Mao’s China. By Angela Jackson. Brighton, Portland, Toronto: Sussex Academic Press, 2012.

“For us it was Heaven.” The Passion, Grief and Fortitude of Patience Darton, from the Spanish Civil War to Mao’s China. By Angela Jackson. Brighton, Portland, Toronto: Sussex Academic Press, 2012.

Patience Darton’s life spanned the turbulent 20th century across two continents. Not only was she a witness, but she also left a remarkably eloquent and original written record in the form of correspondence, the heart of this extraordinary biography by historian Angela Jackson.

Jackson charts, in a vivid and engaging manner, Patience Darton’s extraordinary “outward” journey, from her battles against London hospital bureaucracy—themselves revealing of the severe limitations of British “democracy” in the pre-1945 world—and her midwife’s view of the struggle for survival among the urban poor of East End London to a memorable encounter with the exiled Ethiopian ruler, Haile Selassie, on the doorstep of her Bloomsbury church, and reaches the story’s heart in civil war-torn Spain. The story of “Spain,” i.e., of a deeply felt personal commitment to the same cause of social justice that had first fixed Patience’s resolve among London’s poor, is told in a fresh way that draws in the reader immediately. In particular, the picture she paints of front-line nursing in Republican Spain is vividly rendered, and the telling of its traumatic toll on the medical personnel recalls those edgy truths later brought to us by productions such as M.A.S.H.

But even more than all of this, Jackson gives us, again in hugely evocative—but always precise—prose, the story of Patience’s remarkable inner journey:

You are quite right in saying that it is only in struggling and fighting, not only outside things but things inside ourselves, that make a person. […] Anyway I made a person out of myself, and became an individual with a life and work of my own.

This is what makes the book stand out as a real gem. Patience’s story is extraordinary—inner struggle, existential becoming, self-fulfillment, tragedy, gritty survival, mental fortitude and undying love-in-memory. But the power lies in the telling, in the way in which Patience herself was supremely capable of revealing her experience in luminous prose. Patience’s words, her wit, and her arresting, often heartbreaking, style, are the secret weapons in this story.

There are so many resonant vignettes in the text that it is difficult to single any out. My own choice would be Patience’s telling of the three Finnish International Brigaders, mortally wounded in the battle of the Ebro in 1938, who die, untranslated—a story which, as told by Patience, conveys far more than its content:

We were very good with the Brigades in the hospitals about trying to get somebody who spoke their language, because that was always a dreadful thing with very ill people, dying people—they couldn’t speak—different tongues, you see. And that was where the Commissars came in. Very often there were a lot of Jewish people in the Brigades, a great many, and a lot of them spoke Yiddish and something else. And you would always try to get a Jewish person who could speak Yiddish, to another Jewish person—it didn’t matter if they were Romanian or Hungarian or what they were, you could get a common language, get a message if you wanted it, that they wanted to send home or say who they were or something like that. But we had on the Ebro, in that cave, three Finns and nobody could speak anything to them. Nobody speaks Finnish. They were all very bad chest wounds. In those days we didn’t know that you could operate on chest wounds, we used to strap them up tight and sit them up, but they were miserable. They couldn’t breathe; they were strapped up tight as well as being with all these dreadful flesh wounds, very deep ones. And they were all three dying. And we couldn’t get anyone who spoke Finnish and they weren’t Jewish. Oh! I’ll never forget them; they were such beautiful creatures, great blonde things, you know [sigh] unable to say anything.

Patience Darton’s life is an encapsulation of some of the 20th century’s most critical moments. Without an ounce of didacticism, her life shows the reader the abiding truth of “the personal is political.” No didacticism then, just a truth rendered with grace and melancholy (wrenching understatement is Patience’s forte) and delivered in a way that speaks directly to the sensibilities of the contemporary reader. This is why I highlight the story of the Finnish volunteers—for it seems to me that this book achieves quite beautifully the big challenge of “translating the 1930s” for today’s readers. Patience’s is a unique voice that locks into a rich seam of memory, illuminating the big historical picture while never losing sight of the particularity of heartbreaking loss. This is a subtle, moving story—exquisitely told.

Helen Graham is a professor of Spanish history at Royal Holloway, University of London.