Honoring my uncle Phil Schachter

I have always known about the Abraham Lincoln Brigade. It was part of my family’s proud heritage. My Aunt Toby Jensky was a nurse and administrator in the American Medical Bureau to Aid Spanish Democracy and worked at the Villa Paz Hospital and the Teruel front. My Uncle Phil Schachter was in a machine gun squad, #4 company in the Washington Battalion under the command of Walter Garland.

I knew my Aunt Toby from visiting her in Montville, Massachusetts every summer as a child and then on occasion as an adult. She spoke some of Spain but at the time I didn’t know what to ask. My cousin Bernice Jensky says it was like pulling teeth to get Toby to talk much about it. My cousin Rob Schachter says he remembers Lincoln Veterans visiting Toby all the time but they were just family friends and he didn’t consider at the time their significance. I will always remember Toby with fondness for her generous, matter-of-fact personhood.

I knew my Uncle Phil through my father, Harry Schachter, who carried a deep grief and more complex emotions of regret and guilt regarding Phil. They both shared political beliefs as youths in the Communist Party, the organization that articulated a Marxist promise of a new world and it captured their burning hopes for humanity. And they both were passionate about the cause of the era – to aid the Spanish Republic from the fascist attack and help a beleaguered people. Phil became the one to go to Spain and only Harry and Toby supposedly knew where he went. Everyone else – his bother Max, his sister, Rose and his father, “Pop” were told only he went to Paris. It would seem his sister-in-law Jenks (Toby’s sister) must have known, but the main thing was to keep it a secret from Pop so as to not cause him to worry.

Phil’s letters came from Spain in May and June, 1937, and then they stopped. At first they tried to get Toby to find out what happened and then with no clear information tried to enlist others. Jo Labanyi, Professor of Spanish at NYU studied the archives of Toby and Phil and wrote about my family’s frantic search for Phil in her essay “Finding Emotions in the Archives.” Her research identified the fear and distress that overcame my family. From later correspondence, it was learned that Phil had trained with his company at Madrigueras, came up behind the Jarama lines and then to the jumping off point for the attack of Brunete and Mosquito Ridge. There are no records of him having been taken prisoner. It was surmised he must have died in the Battle of Brunete where so many had died.

My family never knew how to fully grieve Phil and it left a hole in the family fabric. For them, he left and never returned; he was somehow lost. No one could say where, when, or how he died, they could not bury his body, they could not say Kaddish. My father would tear up when he spoke of Phil, remembering Pop learning of Phil’s death. And he felt responsible for having encouraged Phil to go to Spain. This became even more so when my father learned the truth about Stalin’s crimes. He felt shocked, betrayed and disillusioned. Honoring Phil’s memory and the Abraham Lincoln Brigade became intertwined with the Communist Party’s affiliation with Stalin’s Soviet Union and their organizing of the International Brigades. This became a deeper sorrow.

My grandfather, Pop, died decades ago, living into his eighties. My father, when he was dying eighteen years ago, spoke of only a few concerns – one of them was Phil. And in the remaining years, those I knew in that generation died – Toby, Max, Rose and lastly Jenks. Often, when I would receive my copy of The Volunteer, I wondered if there would be any way I could honor my Uncle Phil.

Life has a way of coming around. This year, in late February, early March, 2012, I had the good fortune of traveling to Spain for the first time in my life. I had come to Spain to accompany my 15-year old daughter, Amalyah who has become a serious student of flamenco dance. We traveled to Jerez de la Frontera, in Andalusia, for the two-week flamenco festival. In planning the trip I had made some preliminary contacts with Alan Warren of Porta de la Historia and Ernesto Viñas of Brunete en la Memoria. They were very encouraging and welcoming of planning any kind of visit I might want but it became too difficult to plan ahead given the main purpose of my trip. After about a week of being immersed in the deeply emotional culture and rhythms of flamenco, I had a dream about my Uncle Phil. I knew it was not enough to be on Spanish soil, I needed to visit Brunete.

On March 6th, I headed out early to Madrid and then on a bus to Brunete. It took many hours but I hardly noticed, I was in another world. I carried with me so much mythology of the Lincoln Brigades and felt a shared intense hopefulness that I imagined propelled the volunteers to travel so far to give of their lives. Along with this, I brought my family grief that sought healing. In my backpack I had Phil’s letters, Ernest Hemingway’s heralding the honor of those who entered the earth in Spain, La Pasionaria’s farewell and invitation to return to Spain, and a correspondence dated from 1979 – 1992 between my father and Carl Geiser, an ammunition carrier in the same machine gun company with Phil, where my father speaks of trying to come to terms with Phil’s death.

It’s no wonder I was a bit disoriented to get off the bus and find Brunete was an actual contemporary town. It lived inside me in black and white imagery of the 1930’s civil war era. There was an out of place elaborate colonial central plaza, with a church and two memorials dated 1946 attributing it’s restoration to Francisco Franco. I learned later it was built by Republican prisoners after Franco took control of the city.

I was soon met by Ernesto Viñas who greeted me warmly like I had returned home. He drove me to the outskirts of the city and we walked to the two regions that framed the battle. It is used for grazing and although the land was very parched, we did meet up with a large herd of sheep and goats at the riverbed. Ernesto developed a friendliness with the owner of the land so he waved us along, giving permission to trespass. In our extended conversation, Ernesto told me about interviewing many old people he’d just meet on the streets so he had stories he recorded from those who fought on both sides. I was interested in how the civil war was remembered and studied in Spain, especially since Franco’s death. Seems like it’s still difficult to talk about.

Ernesto brought maps, aerial photos and explained more military strategy and details about the three-week battle than I ever thought I wanted to know. But what became so clear was how utterly insufficient militarily the Republican side was for this offensive, in all ways, except in sheer passion for their cause. This history is of course well known. But there was something more significant here. Walking along the thirsty earth, along the same shallow valleys and hillsides that the men had trekked, looked out into the horizon from, dug trenches in for cover, fought over — all this evoked a connection that was palpable. Coming upon trenches that could still be evidenced and learning about all the relics Ernesto’s found from this abandoned battlefield – bullets, grenade shells, identification tags, sardine cans opened by bayonet, helmets, medicine bottles, and much more (all that I saw later in the “museum” he has organized in his basement) — immersing myself in this landscape allowed me to know this history in a visceral way. I was able to feel for the desperate vulnerable circumstances the soldiers were commanded to fight under. I could somehow imagine the men themselves who had fought there, and those who died there.

We came to the top of Mosquito Ridge where there was an old bombed out brick structure, the only one around. It was here I was left alone to attend to the more personal part of my visit. Here, kneeling down touching the earth, I felt very close to my Uncle Phil, so I spoke to him. I told him he was never forgotten, that everyone tried to find him and say good bye but no one knew how to find him, but that finally, I had. I told him I had everyone with me – the love of Max, and Jenks, Rose and Toby, Pop and my father Harry. I told him about my current family, my husband Emmett and my teenage daughters Rachel and Amalyah who along with many friends and family were all with us here in their thoughts and interest. I told him I didn’t need him to be a hero, and that I knew how much he missed his family when he got to Spain. I told him we honored his goodness and idealism and that the world turned out to be a much more politically complicated truth than he could have known then. I told him that his coming to Spain with the Abraham Lincoln Brigade, his willingness to give everything he had believing it could make the world more fair, more free – that this volunteering, hopeful spirit was a source of profound inspiration. Then I paused, and somehow I managed to say kaddish for this son, brother, uncle. All this brought up enormous emotion. It hardly seemed just my own, or my family’s. Felt part of a universal sorrow for the human struggle that played out in Spain during those dark days that were just the beginning of the trauma and tragedy that overcame all of Europe and throughout the world. Before leaving, I placed some stones I brought from home on the window wall of the brick structure.

I was fortunate to be able to return to Andalusia for several days before needing to return home. From the passion of the flamenco musicians and dancers, I experienced the vitality of the Spanish culture and people. Flamenco, originating so far back in time, from several oppressed minority peoples, reminded me of their creativity and capacity to survive and endure the many eras of injustice and hardship. Reflecting on my visit as I returned, I became convinced of the tremendous value of visiting the places in Spain, and supporting the work of those, like Alan Warren, Ernesto Viñas and their colleagues, where the history of the International Brigades and Spanish Civil War can be engaged with and remembered. This is a history that asks us to consider what moves us to speak out, to stand up, to sign up to give of our energy, our abilities, our lives. And for those who have a particular interest or connection to this history, it can assist us to connect with that which may have gotten lost or left unknown somehow. I returned with a new relationship to my Uncle Phil and how I honor and carry his memory. I offer this rich legacy to my children and recognize its relevance to their youthful passion to want to make a more just world.

Rebecca Schachter, LICSW is a Psychotherapist in Northampton Massachusetts, with a specialization in trauma.

Enjoyed talking with you at the The Cookhouse and enjoyed your article. Jim

One correction –

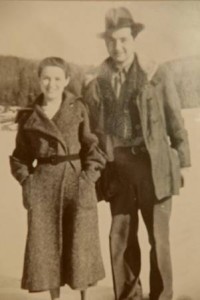

Photograph is of Jenks, Toby’s sister, not Toby.

R. Schachter

Dear Rebecca,

What a wonderful tribute and what a great piece of writing! Thanks so much for sharing such a moving story with all of us.

It seems to me that documenting the “hidden costs” of the sacrifices made by the Lincoln vets –indeed, by all of the defenders of the Republic– is an urgent task for all of us. Even the most complete rosters and bios of the volunteers can’t begin to capture the grief and, in many cases, guilt, of those who were left behind –parents, spouses, friends, siblings– each time a volunteer was swallowed up by the Spanish earth, when, as Hemingway would put it, there was no time for headboards. Grief and guilt that the survivors carried around with them their entire lives, and that in many cases they transmitted to the next generation(s).

But in the end your text is moving and uplifiting, because it is ultimately more about gains than costs, more about the incalculable and timeless and probably unforeseen benefits of the sacrifices made by the vets. Because what I can see being transmitted from one generation to the next in your story is not so much trauma, but rather an intense engagement with the here-and-now, and a willingness to make an honest effort to dialogue with the past, to recognize its complexities while rendering tribute to those men and women who, imperfections and all, refused to be stymied or paralyzed by the messiness of it all.

Thanks for reminding us how that engagement with the present and that openness to dialogue with the past is probably the greatest legacy of the Lincoln vets, one that will help us “outlive all systems of tyranny.”

Best wishes,

James D. Fernández

This tribute really allows us to see what the men and women of the Abraham Lincoln Brigade were giving up in order to fight against oppression in Spain. Phil Shachter left his family to fight for what he felt was right, in a country that was not his own. He was forced to lie to his own Father in order to alleviate worry. Shachter along with all the other fighters of the Brigade were brave honorable Americans that deserve to be remembered. Thank you for writing this tribute to him, it helps keep their memory alive.

I had no relatives in the Spanish War, but have visited some of the scenarios (Orihuela, Albacete, Gandesa, Teruel), and felt the same emotions you describe.

You did not return home with a new relationship to your Uncle Phil. You returned with a new relationship to yourself and to Humankind. Thanks for your moving words!

I, too, lost my 21 year old uncle. He was part of the Abraham Lincoln Brigade as well. He joined the Merchant Marine and left the ship in France and made his way to Spain in 1938. He did not tell his parents nor family living in Pittsburgh, PA and my mom searched for him for decades. I have her letters used in her search including one to President Truman. My husband and I did our research in the Lincoln Brigade Archives at NYU. We then were put in contact with Alan Warren who took us on the path my uncle would have traveled until his death in the battle of Ebro a week after he arrived. It was quite emotional for my husband, myself and son, who is named after Sam Markowitz. We appreciate the research Alan did and he put us in contact with the Sinagoga Major in Barcelona where we added Sam’s name to their Lincoln Brigade plaque.

Because of the communist connections, no one discussed family members who fought. You and your employability would be at risk. These idealists lived and died quietly. They followed their passion and many died. It is time to tell their stories.