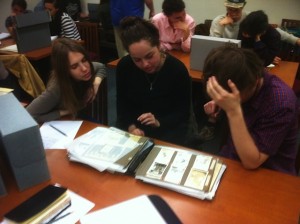

Bard College Students in the Archive

“I felt I was not reading history, I was helping to write it,” said one of the Bard College students who visited the Abraham Lincoln Brigade Archives (ALBA) on March 16. Our visit to the Archives took place during my course “Representations of the Spanish Civil War” and proved to be a memorable experience for my eighteen students—who were conducting archival research for the first time—and for me as an educator.

The visit was part of a course that offered a selection of fiction, plays, films, and art produced both during the war and in the years thereafter, as well as eyewitness testimony. This opportunity to work with primary sources was suggested by Professor James D. Fernández, vice-chair of ALBA, back in November, when he persuaded me to incorporate archival work as a central component of the course. After our visit, my students each wrote a paper on one of the six different collections of documents that were selected for us.

Some of the students decided to focus on a specific topic that caught their attention. This was the case with a student who explored why James Lardner, an accomplished journalist and friend of Ernest Hemingway, enrolled in the Lincoln Brigade after he visited Barcelona in 1938 “when he could expect little personal gain from such a fight.” The questionnaires that psychologist John Dollard designed to investigate the effects of modern warfare in veterans caught the attention of another student, particularly the single signed questionnaire in this collection of anonymous responses. This student paid attention to the responses of William Aalto, focusing on his marginalia, in which Aalto reacted against some of the questions that the veteran believed did not describe his experience in Spain. The time this student spent with Aalto’s questionnaire allowed him to inquire into the relevance of looking at this marginal writing as a construction of history.

Marjorie Polon, a fourteen-year-old New Yorker, exchanged letters with pen pals in Spain, and sent them cigarettes. Her pen pals were six American volunteers and a Spanish soldier, and their letters soon became, as one of my students interpreted them, “vital lifelines, letters that provided moral stamina for the soldiers.” The letters the volunteers addressed to Marjorie were read, in this case, within the frame of the epistolary genre. All in all, the Abraham Lincoln Brigade Archives offered my students the occasion to connect their interests with the subject matter. One student’s paper reconstructed the engagement of American volunteers with civil rights. Bernard Danchik, an American athlete who participated in the 1936 Popular Olympics in Barcelona, kept a scrapbook in which my student read Danchik’s defense of the black athletes who were part of the American team.

The outcomes of our work at the archives were many, and manifested in the papers my students wrote after their visit and their assessment of the experience. A student admitted that this was a unique opportunity to work with primary sources: “You feel more connected to the person who wrote it, it seems more authentic.” After spending a full day in the archives and writing a paper on his discoveries, one of my students expressed the impact her experience had on her understanding of the Spanish Civil War.

Students in my class had been researching the history of the Lincoln Brigade for three weeks before they arrived at the Tamiment library. Their understanding of the motivations and experiences of the volunteers was quite comprehensive. They read transcripts of the letters the volunteers sent to their families and listened to their oral testimony. Professor Fernández visited Bard College to introduce the archives and offered the students a new perspective on the particularities of working with primary sources. As valuable as all these experiences were in helping them maximize their time at the archive, they only realized the benefits of their hands-on practice with letters and artifacts when they arrived at the archive. “You don’t have to rely on someone else’s interpretation,” a student answered when asked about their first impressions of the Tamiment by Professor Fernández.

Teaching a course on the Spanish Civil War with access to these primary sources is the dream of any educator. I am grateful to ALBA for giving me the opportunity to introduce my students to archival work, and for offering the means for successful undergraduate research.

David Rodríguez Solás is a Visiting Assistant Professor of Spanish at Bard College. He has just published the article “Remembered and Recovered: Bethune and the Canadian Blood Transfusion Unit in Málaga, 1937” in the Revista Canadiense de Estudios Hispánicos.