Unfinished journey: U.S. Spaniards face the Civil War

On March 27, 1938, Avelino González Mallada, former mayor of the Asturian city of Gijón, died in a car crash on a country road in Woodstock, Virginia. The next day, The New York Times explained that “Señor Mallada was in this country on a sixty-day permit granted to him by the Department of Labor after he had appealed a ban on his entry imposed at Ellis Island by immigration officials upon his arrival here on February 16.” Other papers reported that González was here to carry out a fundraising tour on behalf of the Spanish Republic and had plans to travel as far as California, addressing groups of Spanish immigrants along the way. An article in the Washington Post later reported that on the night of the wreck, González Mallada “was en route to Beckley, West Virginia to address a meeting of Spaniards there.”

On March 27, 1938, Avelino González Mallada, former mayor of the Asturian city of Gijón, died in a car crash on a country road in Woodstock, Virginia. The next day, The New York Times explained that “Señor Mallada was in this country on a sixty-day permit granted to him by the Department of Labor after he had appealed a ban on his entry imposed at Ellis Island by immigration officials upon his arrival here on February 16.” Other papers reported that González was here to carry out a fundraising tour on behalf of the Spanish Republic and had plans to travel as far as California, addressing groups of Spanish immigrants along the way. An article in the Washington Post later reported that on the night of the wreck, González Mallada “was en route to Beckley, West Virginia to address a meeting of Spaniards there.”

Spaniards in West Virginia? Groups of Spanish immigrants from New York all the way to California? Enough to warrant a coast-to-coast fundraising tour? Yes indeed.

West Virginia

In the early decades of the twentieth century, there was a significant influx of working-class Spanish immigrants into the United States, a process that reached its peak in the years before World War I and the restrictive immigration laws imposed in the early 1920s. During those two decades, thousands of Spaniards came to the U.S., either directly from Spain or, more often, after stints in other parts of the Spanish-speaking Americas. Like other immigrant groups, Spaniards tended to cluster in regions where certain kinds of work were available and to live together in enclaves, forming networks of solidarity and survival by establishing social clubs, mutual aid societies and the like. By the time the Spanish Civil War broke out in 1936, these small communities of working-class Spaniards dotted the entire map of the country, as can be seen on the nation-wide list of wartime affiliates of the umbrella organization, Sociedades Hispanas Confederadas [Confederation of Spanish Clubs].

Of the 120-odd affiliated Spanish clubs on that list, 12 are located in the state of West Virginia, in places like Holden, Raysal, Fairmont, Warton, Lillybrook, Spelter and, of course, Beckley. In the story of working-class Spanish immigration to the United States, West Virginia is the stage of a crucial chapter or two. Thousands of Spaniards found work either in the coal pits of the southern part of the state or in the zinc foundries further north and organized themselves into the clubs that González Mallada was on his way to visit on that fateful night in the spring of 1938.

The Sunshine State

Had González Mallada continued his fundraising tour, he almost certainly would have visited Tampa, Florida. Tampa was a sleepy town of just a few thousand inhabitants in 1885, when the Spanish cigarmakers Vicente Martínez Ybor and Ignacio Haya decided to relocate their “clear Havana tobacco” cigar factories from Key West to Tampa. (They had relocated in 1869 from Havana to Key West to avoid high tariffs on cigars produced in Cuba and the violence of what would become known as the “Ten Years War.”) Thousands of workers poured into “Ybor City,” primarily from Spain (Asturias, in particular) and Cuba. By 1893, there were so many Cuban and Spanish cigar workers in Tampa that José Martí traveled there from New York to generate support and raise funds for the last push of Cuba’s war of independence from Spain (1895-98).

List of member organizations of the Sociedades Hispanas Confederadas in late 1937. Originally printed in the Brooklyn-based paper "Frente Popular" (15 January 1938), reprinted in Marta Rey García’s invaluable "Stars for Spain: La guerra civil española en los Estados Unidos" (Sada, A Coruña, Edicios do Castro, 1997).

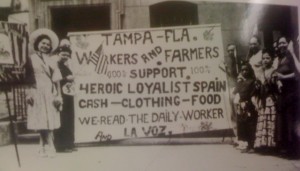

Immigration to Tampa from Spain, often via Cuba, continued unabated during the early decades of the 20th century. Thanks in large part to the presence of a considerable population of working-class Spanish immigrants, Tampa would also be a hotbed of pro-Republican fundraising and mobilization during the Spanish Civil War. “No pasarán,” the rousing pasodoble that became the unofficial anthem of people facing fascism all over the United States, was composed by Leopoldo González, a Tampa-based cigar-factory “lector” or “reader” from Asturias.

Green Mountain Spaniards

González Mallada might have chosen to visit another somewhat unlikely focus of anti-fascist activism during the Spanish Civil War: Barre, Vermont. The town was home to a significant population of working class Spaniards, most of whom had left their native region of Cantabria (Santander) to work in the granite quarries and stone sheds of the Green Mountain State.

The passage of time, the dispersal of the town’s Spanish community, and the corrosive ideological work of the Cold War have all but erased the history of Barre’s antifascism. Thankfully, an article written just after the end of the Spanish Civil War by Miss Mary Tomasi for the Federal Writers Project gives us a priceless snapshot of what González Mallada would have found in the town’s “Club Español”:

From the far wall letters in shrieking red prophesy, ¡Morirá el fascismo!… The Club overlooks North Main Street, just above Barre’s “deadline.” The furnishings are simple, practical. Smooth-worn benches line the walls…

John Bavine, born Juan Bavine some sixty-five years ago in Santander, Spain, is El Club’s efficient secretary…

“We Spanish are good Loyalists, —so you see by the walls—.” Bavine indicated the vivid posters. “Our Club has done good work for the victims of Fascism. In France there are 500,000 refugees in concentration camps. That war in Spain, it started in July of 1936. It did not take us in America long to lend a hand.” Bavine took a Club ledger from the shelf. “See,” he ran a stubby, calloused finger down a page with fine writing. It was in Spanish, neat, the letters much like printing. “See, here is the record. It say we start to take in contributions in August. That is fast work, no? Since then, up to date, we have taken in $15,000. Just here in Barre. Oh there are many ways we raise money. Festivals, dances, picnics, now we even have little stamps…”

On the Pacific Coast

Had González Mallada made it all the way out to the West Coast, he probably would have addressed the protagonists of one of the strangest and least studied waves of Spanish immigration to the United States. In the decade after 1900, some 8,000 Spaniards—mostly from Andalucía—were recruited to work on the sugar cane plantations of the Hawaiian islands. Working conditions were awful, and many of the Spaniards re-emigrated to California as soon as they could, settling in places like the Monterey peninsula, where they often worked in canneries, or in the state’s Central Valley, where they harvested crops in the fruit and nut orchards. Throughout the Spanish Civil War, immigrant organizations all over the state of California organized rallies, picnics, and film-screenings to raise funds for the Spanish Republic. In one notorious episode that took place in June 1938, the police raided a Vacaville hall and confiscated a print of the documentary film Spain in Flames, which was going to be screened by the Vaca Valley Spanish Societies to raise funds for Spain.

Unfinished Journey, Incomplete Knowledge

We will never know the actual coast-to-coast itinerary that González Mallada had planned in the spring of 1938. But with the list of organizations that made up the Sociedades Hispanas Confederadas and our knowledge of Spanish immigrant communities in the U.S., we can hazard a reasonable guess as to his route by connecting the dots of a spotty archipelago of communities of Spanish antifascist solidarity: from the East coast groups sketched out here, through the steelworkers of Canton, Ohio; the zinc workers of Cherryvale, Kansas; and the Basque shepherds and inn-keepers of Nevada, Montana, and Idaho; all the way to the pruners and canners in places like Vacaville, California.

The unfinished journey of González Mallada is an apt metaphor for our incomplete understanding of the depth and breadth of anti-fascist mobilization in the United States around the issues of the Spanish Civil War and, in particular, of the role of Spanish immigrants in that process. We know, for example, that the Confederated Spanish Societies and the Tampa-based Comité Popular Democrático together raised almost two-thirds as much money for the Republic as the much larger and well-studied American Medical Bureau and North American Committee to Aid Spanish Democracy ($520K/ $805K). We know, moreover, that roughly 10 percent of the last names on the Lincoln Brigade roster are Hispanic. And yet many of our research and outreach projects seem to ignore or marginalize the fact that a significant portion of “American” involvement in the Spanish Civil War was carried out by Spaniards, in Spanish. Ya es hora de remediar esta situación y así, de paso, rendir tributo al desafortunado viajero, Avelino González Mallada.

ALBA Vice Chair James D. Fernández is currently conducting research on the Spanish communities in the United States during the 1930s. Read more of his recent blog posts here.

If the United States was practicing non-intervention during this time, how was Mr. Gonázles Mallada able to fund raise across the country?

Hi, Tanner. Good question. The embargo did not apply to medical and humanitarian aid (ambulances, medical supplies, food, clothing, etc.).

Fascism was a movement in Italy by Benito Mussolini. Franco had nothing to do with Fascism…… or as much as England did when they were cozy with Hitler until they saw the light.

Spain was being destroyed by socialism/communism…murdering of politicians, priests, nuns…burning of churches. Franco and brave spaniards HAD to do something agaisnt this.

Stupid spaniards in the US got dupped!

Dear Frank,

Thanks so much for the visit and the comment. As I’m sure you know, there is a vast and complex scholarly debate about the “fascist” nature of Francoism in Spain. The debate is particularly rich and fascinating in part because Franco was such an astute political actor: he often played his cards close to his vest, and he cleverly re-invented himself, his rhetoric and his program as circumstances demanded. The best example of this is probably how, when he saw the writing on the wall regarding the end of WWII, he retooled himself, playing down his “dalliance” with Hitler and Mussolini, and putting himself and his regime forth as an anticommunist bulwark. Many have been “duped” by this bait and switch, and they take the Franco who met with Eisenhower to be the Franco who met with Hitler.

It is interesting to note how, at the time of this re-fashioning the Allies were on to Franco, and fortunately, they committed these views to writing. I close with two examples:

1) Opening statement from the US Department of State, from the publication “The Spanish Government and the Axis,” a collection of the wartime correspondence between Franco, Hitler and Mussolini which was discovered in Germany in 1945:

THE GOVERNMENTS of France, the United Kingdom, and the United States of America have exchanged views with regard to the present Spanish Government and their relations with that regime. It is agreed that so long as General Franco continues in control of Spain, the Spanish people cannot anticipate full and cordial association with those nations of the world which have, by common effort, brought defeat to German Nazism and Italian Fascism, which aided the present Spanish regime in its rise to power and after which the regime was patterned.

There is no intention of interfering in the internal affairs of Spain. The Spanish people themselves must in the long run work out their own destiny. In spite of the present regime’s repressive measures against orderly efforts of the Spanish people to organize and give expression to their political aspirations, the three Governments are hopeful that the Spanish people will not again be subjected to the horrors and bitterness of civil strife.

On the contrary, it is hoped that leading patriotic and liberal-minded Spaniards may soon find means to bring about a peaceful withdrawal of Franco, the abolition of the Falange, and the establishment of an interim or caretaker government under which the Spanish people may have an opportunity freely to determine the type of government they wish to have and to choose their leaders. Political amnesty, return of exiled Spaniards, freedom of assembly and political association and provision for free public elections are essential. An interim government which would be and would remain dedicated to these ends should receive the recognition and support of all freedom-loving peoples.

Such recognition would include full diplomatic relations and the taking of such practical measures to assist in the solution of Spain’s economic problems as may be practicable in the circumstances prevailing. Such measures are not now possible. The question of the maintenance or termination by the Governments of France the United Kingdom, and the United States of diplomatic relations with the present Spanish regime is a matter to be decided in the light of events and after taking into account the efforts of the Spanish people to achieve their own freedom.

THE SPANISH GOVERNMENT AND THE AXIS : Documents DEPARTMENT OF STATE Publication 2483 EUROPEAN SERIES 8 Washington, DC : Government Printing Office, 1946

Available on-line:

http://avalon.law.yale.edu/wwii/sp01.asp

2) My Dear Mr. Armour: In connection with your new assignment as ambassador to Madrid I want you to have a frank statement of my views with regard to our relations with Spain.

Having been helped to power by Fascist Italy and Nazi Germany, and having patterned itself along totalitarian lines, the present regime in Spain is naturally the subject of distrust by a great many American citizens who find it difficult to see the justification for this country to continue to maintain relations with such a regime. Most certainly we do not forget Spain’s official position with and assistance to our Axis enemies at a time when the fortunes of war were less favorable to us, nor can we disregard the activities, aims, organizations, and public utterances of the Falange, both past and present. These memories cannot be wiped out by actions more favorable to us now that we are about to achieve our goal of complete victory over those enemies of ours with whom the present Spanish regime identified itself in the past spiritually and by its public expressions and acts.

The fact that our government maintains formal diplomatic relations with the present Spanish regime should not be interpreted by anyone to imply approval of that regime and its sole party, the Falange, which has been openly hostile to the United States and which has tried to spread its facsict party ideas in the Western Hemisphere. Our victory over Germany will carry with it the extermination of Nazi and similar ideologies.

(FDR to Ambassador Armour in Spain, March 10, 1945; p. 223 in Modern Spain: A Documentary History, ed. Jon Cowans, Philadelphia: University of PA Press, 2003.)

My father Victor C. Canales was born in Barre, VT and returned to near Santander Spain (La Cavada) at an early age due to his father’s silicosis from granite polishing. My father was taken prisoner by the Guardia Civil because he did not register for the Spanish military (Nationalist) at 18 years old. He was eventually traded across the French border for Italian prisoners. He repatriated to NYC and lived above and worked at the Jai-Alia Restaurant (Valentin Aguirre) in Greenwich Village.