Facing Fascism, in Barre, Vermont, for example

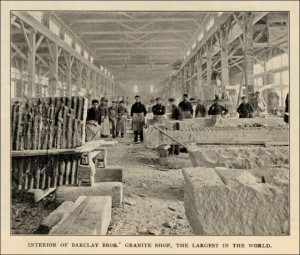

Another somewhat unlikely focus of anti-fascist activism during the Spanish Civil War was Barre, Vermont. The town was home to a significant population of working class Spaniards most of whom had left their native region of Cantabria (Santander) during the first decades of the twentieth century to work in the granite quarries and stone sheds of the Green Mountain State.

Another somewhat unlikely focus of anti-fascist activism during the Spanish Civil War was Barre, Vermont. The town was home to a significant population of working class Spaniards most of whom had left their native region of Cantabria (Santander) during the first decades of the twentieth century to work in the granite quarries and stone sheds of the Green Mountain State.

The passage of time, the dispersal of the town’s Spanish community, and the corrosive ideological work of the Cold War have all but erased the history of Barre’s antifascism. Thankfully, an article written just after the end of the war by Miss Mary Tomasi for the Federal Writers Project gives us a priceless snapshot of how fascism was faced in the town’s “Club Español.”

Barre’s El Club Español: The Spanish Club rooms breathe Old Spain. They flaunt Loyalism…

From the far wall letters in shrieking red prophesy, ¡Morirá el fascismo!… The Club overlooks North Main Street, just above Barre’s ‘deadline.’ The furnishings are simple, practical. Smooth-worn benches line the walls…

John Bavine, born Juan Bavine some sixty-five years ago in Santander, Spain, is El Club’s efficient secretary…

“We Spanish are good Loyalists, –so you see by the walls—.” Bavine indicated the vivid posters. “Our Club has done good work for the victims of Fascism. In France there are 500,000 refugees in concentration camps. That war in Spain, it started in July of 1936. It did not take us in America long to lend a hand.” Bavine took a Club ledger from the shelf. “See,” he ran a stubby, calloused finger down a page with fine writing. It was in Spanish, neat, the letters much like printing. “See, here is the record. It say we start to take in contributions in August. That is fast work, no? Since then, up to date, we have taken in $15,000. Just here in Barre. Oh there are many ways we raise money. Festivals, dances, picnics, Now we even have little stamps…”

“In the United States today there are 176 clubs like this one that raise money for our suffering countrymen. It is what you call a big confraternity these Clubs. We have had a congress in Philadelphia, in Pittsburg, an’ in other large cities. The money we send to the Spanish Confederated Society in New York and to the Medical Bureau to Save Spanish Democracy…”

“Manuel spoke. “You’ve heard about that ship that arrived in Vera Cruz, Mexico, two weeks ago? With 1,900 refugees aboard. Well it was money from our Spanish-American clubs that got them here-”

…Manuel stepped across the room and took from the wall a photograph of a group of young men. perhaps a dozen. He pointed out two in the front row. “These are two of our Barre Loyalists who went over to fight for a just cause. This older one was born in Spain but he’d lived here for a good ten years. This younger fellow was born here in Barre. […] What does my friend do? He’s never seen Spain, but he packs up right away, and goes over to fight. He didn’t come back. He was killed…”

“We had an Ambulance Drive a while back,” Manuel said. “Made $656.00 in one night. Last week we had a Spanish fiesta in the Armory Hall. We took up no collections, only straight admission fees. Eighty cents and fifty-five cents. A professional from New York came to dance for us. Mariquita FLores. A small girl, no more than four feet eleven, but could she dance! She’s touring the country, too, for the victims of Fascism. She gets no pay. Her heart is with the Loyalists. All we did was pay her fare to Barre, and her living expenses while she stayed here. There was a crowd there that night. And not only Spanish people. How much did we make, Bavine?”

“I cannot say for sure,” the older man said. “All the expenses, they have not yet been figure. But I guess there will be a $350.00 more for our poor Spanish-”

[Full text can be seen at: http://lcweb2.loc.gov/cgi-bin/query/D?wpa:10:./temp/~ammem_dxA3::]