Buñuel and the outbreak of the war

The following is an excerpt from Chapter 13 of Luis Buñuel: The Red Years, 1929–1939, published by the University of Wisconsin Press. (Buy the book at Powells and support ALBA.) See also this interview with Román Gubern.

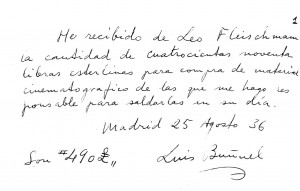

Two sources of information exist about the poorly documented cinematic activities of the director during the first few weeks of the war: the declarations of Antonio del Amo, and Juan Vicens’s archive in the Residencia de Estudiantes. In the latter there is a receipt signed by Luis Buñuel, dated 25 August 1936, which reads: “Received from Leo Fleischman the sum of £490 for the purchase of film material, for which I assume the responsibility of repaying at some future date.” Leo Fleischman was an American engineer, a New Yorker, the brotherin- law of Juan Vicens, which is why this document is in his archive. Before the first American volunteers would embark at the end of the year in New York to fight on the Republican side, Fleischman, who was probably spending his summer holidays in Spain with the Vicenses, enlisted in the Fifth Regiment and died in combat in October 1936.

On 20 July the PCE had organized the Fifth Regiment, consisting of Communist militiamen—harangued that day by Pasionaria—whose first headquarters were in the Salesian convent on Calle Francos Rodríguez in Madrid. In its ranks it introduced “political commissars” on the Soviet model—the painter Ramón Pontones was one of them—and by the end of July it had already sent a thousand combatants to the Sierra de Guadarrama front. Eduardo Ugarte would join the Fifth regiment’s press service, in which he was chief editor of the newspaper Milicia Popular.

An economic relationship between Buñuel and Fleischman existed, then, within the confines of filmmaking activity at the start of the war, when Buñuel had already abandoned Filmófono. The fact that he was the recipient of a rather large sum to buy film material with would suggest that his function was that of an administrator, manager, or organizer. The comments by Communist filmmaker Antonio del Amo about his activities during that period point in the same direction. The earliest and most illuminating were made to Antonio Castro. “When the war started,” del Amo told him, “I, who had always intended to become a director and had tried without success to become Perojo’s assistant, asked a great friend of mine, Buñuel, what I had to do to make films, and Buñuel gave me a 16 mm camera, a hand-cranked Éclair, a good one, and made a present of film he’d got himself from Kodak. With the camera, the negative film and a few cameramen friends I went to the front with Mantilla; in actual fact I went as an assistant to Fernando G. Mantilla, who was Carlos Velo’s collaborator.” Del Amo was twenty-five years old at the time and was known as a movie critic and film society activist, while the likewise Communist Mantilla, a philosophy and arts graduate in 1931, film critic for Unión Radio, and since 1935 co-director of various documentaries with the Galician biologist Carlos Velo, had greater professional experience. It is usually claimed that Mantilla’s first Civil War documentary was Julio 1936, which was commented upon that September in the film press. Produced by the improvised Cooperativa Obrera Cinematográfica, consisting of Communists and a few Socialists, its Communist orientation was evident, since it began with an address by José Díaz, general secretary of the PCE, and concluded with a speech by Pasionaria. It is likely that the workers cooperative film unit had some connection or other with the Fifth Regiment, given the Communist predilection for centralized, unified activity, and it is also plausible that Buñuel was not foreign to its pioneering wartime initiative. In February 1937 the Cooperativa Obrera Cinematográfica presented a project to the Ministry of Press and Propaganda for the reorganization of the film industry, a document in whose gestation Buñuel could have intervened before leaving for Paris.

Receipt in Buñuel's hand, dated 15 August 1936, in which he acknowledges the loan of 490 pouns by American International Brigades member Leo Fleischman for the purchase of film material. (Archivo de la Residencia de Estudiantes, Madrid.)

Buñuel, then, provided the camera and virgin film that del Amo utilized in his early Civil War work. More than twenty years after his statement to Antonio Castro, and with Buñuel dead, del Amo came up with a more self-serving and colorful version of their professional relations during the war, affirming that he went to film with Buñuel at the front, under his direct orders, “and we launched ourselves into the adventure of filming all the confrontations that were taking place on all the battlefields.” More reliable researches indicate that del Amo was Mantilla’s assistant on the documentaries España 1936 (which must not be confused with the film of the same name made in Paris by Buñuel/Dreyfus), produced by the Alliance of Anti-Fascist Intellectuals for the Defense of Culture, and Nueva era en el campo (1937), a Film Popular production for the Ministry of Agriculture. Del Amo was extremely active during the Civil War. He directed the Cinema Section of the Forty-Sixth “El Campesino” Division (led by Valentín González, who was nicknamed thus) of the Fifth Army Corps, following the death of its chief, the Italian cameraman Antonio Vistarini. For it he co-directed, with Rafael Gil, the remarkable Soldados campesinos (1938), using nonprofessional actors. Del Amo was condemned to death at the end of the war, a sentence commuted to thirty years’ imprisonment, thanks to the negotiations of his ex-collaborator Gil, whose life he had previously saved in the opposite political camp. Mantilla, meanwhile, went into exile in Mexico.

The names of Buñuel and Antonio del Amo also appear alongside each other in the dossier held in the General Archive of the Spanish Civil War in relation to the tragic end of the Communist critic Juan Piqueras. In July 1936 Piqueras, who was suffering from a stomach ulcer, traveled from Paris to the Spanish border in response to an invitation from his comrades in Asturias. Once on Spanish soil on 9 July 1936, however, he began to cough up blood and was obliged to take shelter in the inn of the railway station in Venta de Baños (in the province of Palencia) in order to recover. It was there that the military uprising overtook him. On 19 July he wrote a poignant letter to the Communist painter Hernando Viñes in Paris, informing him in detail of the incoming news he had been noting down since the day before. It is worth reproducing this dramatic document, conserved in Vicens’s archive, which begins thus:

The names of Buñuel and Antonio del Amo also appear alongside each other in the dossier held in the General Archive of the Spanish Civil War in relation to the tragic end of the Communist critic Juan Piqueras. In July 1936 Piqueras, who was suffering from a stomach ulcer, traveled from Paris to the Spanish border in response to an invitation from his comrades in Asturias. Once on Spanish soil on 9 July 1936, however, he began to cough up blood and was obliged to take shelter in the inn of the railway station in Venta de Baños (in the province of Palencia) in order to recover. It was there that the military uprising overtook him. On 19 July he wrote a poignant letter to the Communist painter Hernando Viñes in Paris, informing him in detail of the incoming news he had been noting down since the day before. It is worth reproducing this dramatic document, conserved in Vicens’s archive, which begins thus:

Dear Hernando,

I’ve been in Venta de Baños for ten days now. Just imagine that when making my way on Thursday the 9th to Asturias, twenty minutes or so before reaching Venta de Baños, I suffered a hemorrhage in the stomach. I had to put up at the Station Inn, where I’m confined to bed, being cared for by the local doctors. [Juan Antonio] Cabezas came from Oviedo and hasn’t moved from my side. He and the comrades from here have looked after me. In a few days I shall go to Valladolid and get an X-ray done. If I have to be operated on again I’ll go to Madrid. If not, to Oviedo. Don’t say anything to my wife and if you let on to my friends tell them to be very careful not to say anything so that she doesn’t find out. Given all that’s happening I’m very upset about the useless state I’m in. Never have I felt the revolution so close and me here in bed. It’s infuriating. Since I can’t move, I’ve decided to send you a few notes about the information I’m getting. If you give it to the comrades at L’Humanité, warn them not to say that a sick comrade’s involved, etc. Greetings and best wishes,

Piqueras

You can write me c/o the Hotel de France. Valladolid. I expect to be able to move in the next four days.

As I get to find out things I’ll send them to you. Go and see [Paul] Nizan because I’m sure they must be of interest to him and to L’Huma.

On seeing Cabezas and the other comrades armed and ready to defend our February victory, and seeing myself in the state I’m in I was unable to repress an attack of nerves in the face of my uselessness. Cabezas tries to console me a bit. From the stairs we say goodbye with a UHP [Proletarian Brothers United] and our fists held high.

The train stops 1 1⁄4 hours late. Greetings Rot Front [Red Front] Venta de Baños (Palencia)

Saturday 18 [July]: confused and very vague rumors have been arriving all day, last night’s Madrid press says nothing. This morning’s appears with huge blank spaces, imposed by the censors.

At 3 pm some comrades told me they’d heard on the radio that the Minister of the Interior had stated that in Tetuán and other cities of the protectorate [in Morocco] the forces of the Foreign Legion had risen to the cry of “Viva España!” which is the cry of degenerate patriots, the working population confronted them and two hours later they told me once again that in the streets of Tetuán the working masses were fighting the Legion.

At 6 pm they informed me that Largo Caballero has said on the Madrid radio, in the name of the UGT, that in all those places where military forces or Fascist elements show themselves, the workers will respond with the General Strike.

The CNT and UGT have ordered an all-union general strike in all those places where the state of war is declared.

Saturday, 20.00: around 8 pm Cabezas arrived from the Casa del Pueblo where he’d met the committee, which was interceding to defray the costs occasioned by my illness in Venta de Baños. Moments later, a comrade arrived requesting he go because an individual from Asturias had turned up asking for assistance. When asked if he knew Cabezas he said yes. When he went he was able to discover that the man was a common swindler.

Saturday, 21.00: an hour later Cabezas arrived with two more comrades. He told me they were going to look for arms and to detain all the suspicious people in the village. It appears that this order had been given by the Governor of the province. They’d been in a meeting in the Casa del Pueblo studying the ways in which they could prevent the forces in Palencia and Valladolid from uniting. In Valladolid there are three dangerous reactionary regiments and the one in Palencia is the one that already rebelled in Alcalá de Henares. They want to avoid at all costs that in the event that the forces in these provinces are mobilized, they can unite.

Saturday, 22.00: Cabezas has just arrived with some comrades. He tells me they’ve managed to mobilize a hundred men and that he has them ready in case it’s necessary to go and help the men in Palencia.

A bit later he leaves and returns armed with a carbine. He comes with two or three more comrades. They’ve locked up the village Fascists and are going to Palencia. I’m very agitated due to not being able to move.

Cabezas tells me Pasionaria spoke on the Radio along with the Minister of the Interior telling the Communists and workers that they should get weapons and fight. There is no leadership save that of the civil authorities.

At 11 pm the government dismissed five generals. Franco. Mola. Queipo de Llano and two others.

At the same time it announced the dismissal of various members of the high command of the Civil Guard.

Palencia: at 3 am the Civil Governor of the province telephoned the Mayor of Venta de Baños to get him to send the workers’ forces he can, the aim being that on arriving in the town they split up and try and take the strategic sites.

At 3.30 am the mayor, who has been visiting me every day (a good man with anarchistic ideas to whom I’m pointing out the mistaken tactic of the FAI people at this time of a Popular Front in Spain) and who finds himself, precisely, in the Station Inn, where the telephone and telegraph service is installed, has just come up to see me in order to reassure me and he tells me he’d discovered the existence of five wagons full of explosives in the Station. I think their discovery is due to the fact that Cabezas, accustomed to Asturian dynamite, began to ask right away if there were explosives. The mayor, pressed by our comrades, has asked permission of the Governor to requisition them. This he denied to begin with. But moments later he sent him a telegram saying, “Make use of them now and whenever.”

Palencia 5 am. Cabezas has just telephoned the Station Inn telling them to tell me the government is in control of the situation there and that they will return straightaway.

Miners’ train. They assure me the Government has asked for help to the workers’ forces and that a miners’ train is coming from Oviedo.

They tell me that instead of one, two will come and that before reaching Madrid they’ll bring the Fascist forces in Valladolid to book.

Judging by what’s happening here the people identifies with the government.

Seville. General Queipo de Llano seditiously declared a State of War in the Province. The workers replied to this provocation with a General Strike. It seems they took possession of the radio station from which they announced the province is theirs. On the other hand the Minister of the Interior says the Civil Guard and the Assault Guards are facing them and putting up a fight.

4 am, Sunday. Better impressions from Sevilla. The radio is again in the hands of the State.

Malaga 5 am: the Fascists were defeated and a huge popular demonstration took place, which cheered the government forces.

Burgos 5 am. The Commander-in-chief is in military prison.

Valladolid. In this province, where the right-wingers are very strong, it appears that General Mola (that famous assassin of the students of the Universidad de San Carlos in Madrid a few months before the Republic of 14 April [1931]) has taken the railway station with a task force and demands that travelers shout “Viva España!” and “Viva the Fascio!” [Annotated in the margin] 5 generals replaced at 11 pm.

Sunday 5 am. It appears the seditious forces and soldiers are in the street with machine-guns. A Fascist captain has phoned Venta de Baños to say they’re waiting for the miners’ train to riddle it with bullets. Our comrades have taken all sorts of precautions.

Sunday 5 am. They’ve just told me a new Government has been formed: Presidency: [Diego] Martínez Barrios Ministry of the Interior: [Augusto] Barcia War: General [Carlos] Masquelet S[tate] Education: M[arcelino] Domingo Treasury: [Enrique] Ramos Navy: [José] Giral. etc. etc. I’m waiting for the train to Paris to pass at any moment. That’s why everything’s so topsy-turvy.

The train ought to have passed here at 4.30. It’s 5.15 and still it hasn’t passed. This shows that in Valladolid or in Madrid there’s something that’s stopped it leaving or traveling normally.

Juan Piqueras, the Valencian film critic, Communist activist, and close collaborator of Filmófono who was assassinated by the Fascists in July 1936. The portrait dates from 1930. (Institut Valencià de Cinematografia Ricardo Muñoz Suay, Valencia.)

The postmark on the envelope in which Piqueras sent this letter, by express mail, bears the date of 19 July. In the Francoist dossier that contains the documents confiscated from Piqueras there are various interesting items, among them a telegram from Buñuel and del Amo to Piqueras, sent from Madrid on 15 July, which reads “We await a decision to come tomorrow,” which implies that Piqueras had informed his comrades in the capital of his misfortunes. A letter from del Amo to Piqueras the next day was more explicit, since it divulged that Piqueras’s illness was taken as read, and informed him that a meeting of the PCE cell had taken place, before adding:

The first thing I did was phone Buñuel, to say that he was the one who could help me out with his car, since I couldn’t leave for Venta de Baños without money. Buñuel reassured me. He told me you’d written to Urgoiti about your getting better. Anyway, I sent you a telegram, which I suppose you’ll have received, because Buñuel advised me that we oughtn’t to go to Venta de Baños without you informing us of the need there was for it. Today I’ve waited for news from you, but have received nothing before reaching the end of this letter. I hope if you continue being poorly you’ll let me know if it’s essential I come to Venta de Baños. I don’t have money for the trip, if not I would have come already, even though your state of improvement wouldn’t have made it necessary.

In 1980 Antonio del Amo nuanced this information in a letter to Juan Manuel Llopis, Piqueras’s biographer, when relating, “The thing I remember is that I said [to Buñuel], ‘We’ve got to get to Venta de Baños somehow. We can go in your car.’ And he said, ‘They’ve requisitioned my car’ (it was common at the time to requisition cars from all those who had them, be it for the political parties, trade unions and the militias themselves that were springing up at every moment like mushrooms). ‘We might go by train, or in another car, one way or another,’ I interrupted him. And he told me, with good reason, ‘And by what route, if the Somosierra and Alto de los Leones and Navacerrada roads are blocked?’” A certain confusion may be observed in the chronology, since while the correspondence with Piqueras took place before the military uprising, del Amo is referring years later to dates posterior to the insurrection, when Buñuel had already handed over his car to his Communist cell, as Bello explained. In any case, if Buñuel restrained his comrade’s impulse to go and visit the sick man, it is very possible that this somewhat unsupportive attitude saved the two of them from being captured by the Fascists, as occurred to their friend.

English edition copyright © 2012 The Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System Publication of this volume has been made possible, in part, through support from the Program for Cultural Cooperation between Spain’s Ministry of Culture and United States Universities, and from the Anonymous Fund of the College of Letters and Science at the University of Wisconsin–Madison. Wisconsin Film Studies: Patrick McGilligan, series editor