Documentaries of the Lincoln Brigade

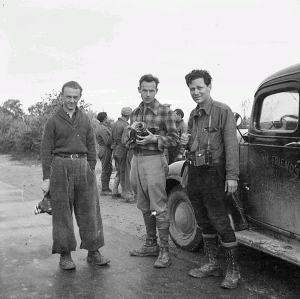

Jacques Lemare, Henri Cartier-Bresson and Herbert Kline during the filming of With the Lincoln Brigade in Spain. (Tamiment Library, NYU, 15th IB Photo Collection, Photo #11_0818)

It was a small war, fought on the fringes of Europe. Its casualties pale by comparison to the savagery of World War II that followed it by only five months. Yet there is something about the Spanish Civil War that insistently draws us back, that compels us to tell and retell the story. The fall of the Spanish Republic in 1939 dashed the hopes and dreams of millions of people around the globe, as Spain’s fledgling democracy was crushed by fascist military might. The Republic’s defeat was the defining moment for an entire generation, for in the words of Albert Camus, “it was in Spain that we learned that one can be right and yet be beaten, that force can vanquish spirit, that there are times when courage is not its own recompense. It is this, doubtless, which explains why so many, the world over, feel the Spanish drama as a personal tragedy.”

- In Spain with the Abraham Lincoln Brigade (1937), by Henri Cartier-Bresson, Jacques Lemore, and Herbert Kline;

- Dreams and Nightmares (1974), by Lincoln vet Abe Osheroff;

- Europe Between the Wars (1978), by Scott Garen;

- The Good Fight (1984), by Sam Sills, Mary Dore, and Noel Buckner;

- Forever Activists (1990), by Judy Montell (nominated for an Oscar);

- Into the Fire (2002), by Julia Newman;

- Souls without Borders (2006), by Miguel Ángel Nieto and Anthony Geist.

In preparing this piece I had the extraordinary experience of viewing in two days the films listed above, all of them for at least the second time, others many more than that. And a curious thing happened when I sat down to write: I had difficulty telling them apart. Not, of course, in their broad sweep. It would be impossible to confuse Osheroff’s personal memoir Dreams and Nightmares, for instance, with the testimony of the American nurses in Newman’s Into the Fire. Rather, it was in the details, and more specifically in the archival footage, where I had difficulty distinguishing them. From Dreams and Nightmares in 1975 to Souls without Borders in 2006, all these documentaries seem to draw on the same pool of images.

The Spanish Civil War was the most photographed and filmed military conflict up to that point in history. Technological innovations—principal among them the compact single lens reflex 35 mm. camera and lightweight movie cameras—revolutionized the visual documentation of war. This allowed photojournalists and cameramen to get closer to the action and to record it with unprecedented immediacy. In addition, cinema newsreels were a burgeoning market for footage from Spain. A great deal of this material has been preserved in archives around the world.

It turns out that much of the footage recycled through the subsequent documentaries, in fact, originates in Cartier-Bresson’s short silent film, shot in a very few days and created with the avowed intention of influencing American public opinion and policy in defense of the Republic. I should point out that the material was used without attribution to Cartier-Bresson not out of malice, but because it wasn’t identified as his. These are some of the scenes that recur time and again:

- basic training in Albacete, new volunteers marching over dusty fields;

- Commander Robert Merriman addressing the troops, one in a long string of speeches for which the Lincolns, as many of them later confessed, had little tolerance;

- lining up for a meager meal of soup and bread;

- naked bodies lathering up in a mobile hot shower provided by the French Steelworkers Union;

- wounded Lincolns recovering in the hospital in Benicàssim;

- and, most memorably, portraits of the American volunteers.

There is one sequence often repeated that I find very moving, a slow pan across the faces of a group of young men, many of whom would later die in battle, others of whom would survive to tell the story. The camera lingers on one soldier’s face before slowly gliding down his body to his waist, traveling across the machine gun he is holding horizontal to the ground, to the comrade on his left, who grips the other end of the weapon, before slowly traveling up his torso to his face. Their youth and determination shine through in shy smiles, shrugs of the shoulders, a deep drag on a cigarette. Or do they? Is it perhaps the narrative constructed with these images that makes us see commitment in these young faces?

In Spain with the Abraham Lincoln Brigade establishes many of the elements that will become part of the paradigm of the American volunteers. This includes the concept of steely commitment to the cause; the emphasis on racial and ethnic diversity (we see African Americans and Asians shoulder to shoulder with white Americans) will be elaborated as one of the proudest distinctions of the Brigade, culminating in the promotion of Oliver Law to commander and his death leading the troops up Mosquito Hill in Brunete; the gallery of portraits of the volunteers, many of whom are identified by name, trade, and hometown, will be transformed into interviews with surviving participants in later documentaries. Finally, since this is a silent film, the narrative line is carried by printed texts, often serving as transitions between different scenes as well. In its descendents, this will become voice-over narration, used in all but Souls without Borders. Cartier-Bresson’s film sets in place the main elements and parameters of how the story of the Lincoln Brigade will be told from that moment until today.

With slight variations the story is told in this way. It begins with conditions in the U.S., masses of unemployed thrown into desperation and poverty by the Great Depression; involvement in the labor movement, organization of the unemployed, and radical ideologies that envision a more just world; while this is happening on the home front there is a growing awareness of fascism in Italy and Germany, and the accompanying sense of impotence; Spain finally takes a stand against fascism and is abandoned by her sister democracies, including the U.S.; the formation of the International Brigades finally makes it possible to fight back, and the young Americans hike over the Pyrenees into Spain or swim ashore after their ship is torpedoed; archival footage of scenes of key battles—Jarama, Brunete, Belchite; Pasionaria’s moving Despedida when the internationals are withdrawn in 1938—“You are history, you are legend”; and then normally a coda that varies from film to film and either tells about persecution in the McCarthy witch hunts or follows the ongoing social and political activism of a few veterans. All the documentaries under consideration follow this paradigm to a greater or lesser extent.

I do not mean to imply that this is not an accurate representation of the events, but I am interested in understanding how it came to be the dominant narrative of the Lincoln Brigade. Chronology, of course, is always a compelling organizing principle. But is this the only way to tell the story? Fredric Jameson reminds us that history is not narrative, it is blood and struggle, but that our only access to history is through narrative.

I believe that the story continues to be told in this way in response to an unacknowledged master narrative that hovers, unspoken, over all these films, and that is the discourse of the Cold War. Even before the defeat of fascism in Europe, the Soviet Union lurked on the horizon as the next enemy. Lincoln vets suffered persecution and discrimination after Spain. Labeled “Premature Antifascists,” they were kept from active combat duty by the U.S. military until later in World War II. They were considered subversives and “Un-American,” and many were imprisoned or lost their jobs and passports.

I believe that the story continues to be told in this way in response to an unacknowledged master narrative that hovers, unspoken, over all these films, and that is the discourse of the Cold War. Even before the defeat of fascism in Europe, the Soviet Union lurked on the horizon as the next enemy. Lincoln vets suffered persecution and discrimination after Spain. Labeled “Premature Antifascists,” they were kept from active combat duty by the U.S. military until later in World War II. They were considered subversives and “Un-American,” and many were imprisoned or lost their jobs and passports.

There are a number of ways to understand the story of the Lincoln Brigade as a counter-Cold War narrative. In the 1940s and 50s, members of the American Communist Party were frequently considered foreign agents by the U.S. government. In these documentaries, the veterans’ testimonies often stress a nativist perspective. They unanimously express anger and dismay as Americans at FDR’s failure to support the Republican cause. In The Good Fight, Bill McCarthy tells us that the Spanish people were just fighting for what we already had: the right to vote, equality, and democratic political institutions. The African-American nurse, Salaria Kea, echoes this sentiment in the same documentary and in Into the Fire. The volunteers are presented as independent thinkers rather than as “dupes of Stalin.” Several of them recount their rejection of the CP line and discipline, expressing their scorn for Party functionaries and pie-cards. A repeated emphasis on Popular Front ideology draws attention away from the prominence of the Communist Party in the Spanish struggle. It makes a good story, and it has not gone uncontested by neo-cons such as Ronald Radosh.

Yet it raises other questions about the nature of memory and how it is constructed, about the role of visual documents in memory formation. Photographs and film footage are in one sense frozen moments in time. At the same time, they have an ongoing afterlife and become woven into the very fabric of memory. This afterlife changes with the passage of time and the different contexts into which they are inscribed. Our memory of a war waged over 70 years ago and of the Americans who fought in it is, in fact, built in large part on these images, their sequencing and contextualization not in life but in narrative structures.

And this, in turn, brings up another issue, that of truth value and authenticity. The source of much of the footage, Cartier-Bresson’s film, was self-acknowledged propaganda, created to persuade and convince, to sway public opinion and influence foreign policy. It makes little pretense of objectivity. Juan Salas found the diary of a Spanish miliciano who trained with the Lincolns at the time Cartier-Bresson shot the footage. The Spaniard complains about the staged battle scenes. Controversy rages today over Capa and Taro staging scenes and posing soldiers, not the least of which is the ongoing polemic over Capa’s Fallen Soldier.

As these images, both moving and still, migrate to the documentary narratives of the Lincoln Brigade and are recontextualized, the distinction between reality and simulation, to the extent that it existed originally, becomes flattened and blurred. Staged scenes as well as newsreel footage of real battle acquire the status of truth and become the foundation for our memory of the Spanish Civil War and the American volunteers. Does this make the story less real or our memory less authentic? Abe Osheroff, when asked if his tales of Spain were true, often replied, “Look at it this way: either it’s true or I’m a genius….” Translation: truth is in the telling.