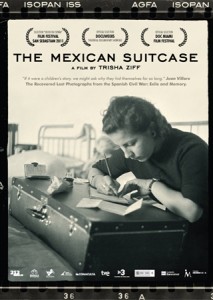

The Mexican Suitcase, by Trisha Ziff

Two-thirds of the way into Trisha Ziff’s brilliant documentary about the re-discovery in Mexico of 4,500 Spanish Civil War photographic negatives of Robert Capa, Gerda Taro and David Seymour, two Mexican intellectuals comment on the donation of that vast archive to the International Center of Photography in New York. Photographer Pedro Meyer openly says that he wishes that the material had never left Mexico for New York, observing how people in cosmopolitan capitals like New York, Paris and London, often act as if nothing ever happens anywhere else. The novelist Juan Villoro is a bit more nuanced, arguing that in places like New York, experts might know how best to catalogue, archive and preserve things, and how to arrange them in “cosmopolitan galactic displays,” but that precisely because of that cosmopolitan and museographic culture, in New York’s museums and galleries those same things are often torn out of their original contexts, extirpated from the human stories in which they were originally embedded and extracted from the human circuits through which they were meant to circulate, and in which they acquire meaning.

Two-thirds of the way into Trisha Ziff’s brilliant documentary about the re-discovery in Mexico of 4,500 Spanish Civil War photographic negatives of Robert Capa, Gerda Taro and David Seymour, two Mexican intellectuals comment on the donation of that vast archive to the International Center of Photography in New York. Photographer Pedro Meyer openly says that he wishes that the material had never left Mexico for New York, observing how people in cosmopolitan capitals like New York, Paris and London, often act as if nothing ever happens anywhere else. The novelist Juan Villoro is a bit more nuanced, arguing that in places like New York, experts might know how best to catalogue, archive and preserve things, and how to arrange them in “cosmopolitan galactic displays,” but that precisely because of that cosmopolitan and museographic culture, in New York’s museums and galleries those same things are often torn out of their original contexts, extirpated from the human stories in which they were originally embedded and extracted from the human circuits through which they were meant to circulate, and in which they acquire meaning.

The dichotomy invoked by Meyer and Villoro is something of a cliché –though, like many clichés, not without its boulder-sized grain of truth. When taken to its extremes (which Meyer and Villoro do not do), the commonplace opposes a technologically sophisticated and white lab-coat First World, to a telluric Elsewhere where things may be messy and unpreserved, but where they are, at least, Real. In one place, we have preservation protocols, high production values, efficient climate controls, mechanical reproduction, markets and spectators; in the other Place, we have presence, aura, organic circulation, witnesses and communities of meaning. Between the two places: no man’s land.

Ziff’s film itself could be brought forth as Exhibit A in a demonstration of the speciousness of the extreme version of the dichotomy. Like Capa, Taro and Seymour before her, Ziff lives and labors in that no man’s land. This impeccably filmed and edited documentary could easily have used its high production values to insert the newly discovered photographs into a Sothebys-like series of the grand History of Photography, one of those immaculate cosmopolitan and galactic displays which Villoro probably had in mind. Another filmmaker could probably have eliminated Mexico and even Spain from the story, pretending, as Meyer’s observation would seem to predict, that by coming to the capital of the twentieth century, the photographs had finally returned to their proper dust-free, climate-controlled and context-neutral home.

But Ziff does nothing of the sort. In fact, by anchoring the film’s narrative in the living voices of contemporary Spain (with its on-going struggle over the memory of the Spanish Civil War, powerfully represented by the movement to exhume mass graves of Franco’s victims) and in the living voices of contemporary Mexico (with its vibrant community of Spanish Civil War exiles and their descendants), Ziff does exactly the opposite. She uses state-of-the-art tools and high production values to put the images of Capa, Taro and Seymour back into their worldly context, back into circulation after seven decades of silence, and like the bones recovered from a Francoist mass grave, back into the urgent, ethical dialogue across borders, including the border between the dead and the living.

The Mexican Suitcase was presented this evening as part of ALBA’s Human Rights Documentary Festival at the Museum of the City of New York. Ziff was present and the evening was a great success.

This is a thoughtful and insightful review of Trisha Ziff’s film, The Mexican Suitcase. Thank you to Jim Fernandez for saying so quickly what everyone was thinking last night at ALBA’s Human Rights Film Festival screening at the Museum of the City of New York.

Ziff made her point graphically when she cut from an archeologist carefully lifting a skull from its dusty grave directly to a shot of a museum worker carefully lifting the fragile box of negatives. It took

Jim Fernandez’ essay above to give me words to go with my feelings.

I saw this interesting film tonight in Ottawa. Cornell Capa, Robert’s brother, was the founder of the International Centre of Photography in New York, which now holds the negatives. The comment by Pedro Meyer seemed not to acknowledge that.