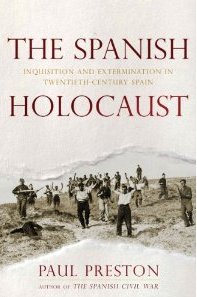

Sneak Preview: Paul Preston on the Spanish Holocaust

Editor’s note: Paul Preston, perhaps the most thorough and prolific historian of the Spanish Civil War, will publish a major new book, The Spanish Holocaust: Inquisition and Extermination in Twentieth-Century Spain, in New York early next year. The following selection is from the book’s prologue.

Behind the lines during the Spanish Civil War, nearly two hundred thousand men and women were murdered extra-judicially or executed after flimsy legal process. They were killed as a result of the military coup of 17-18 July 1936 against the Second Republic. For the same reason, at least three hundred thousand men died at the battle fronts. Unknown numbers of men, women and children were killed in bombing attacks and in the exoduses that followed the occupation of territory by Franco’s military forces. In all of Spain after the final victory of the rebels at the end of March 1939, approximately twenty thousand Republicans were executed. Many more died of disease and malnutrition in overcrowded, unhygienic prisons and concentration camps. Others died in the slave labour conditions of work battalions. More than half a million refugees were forced into exile and many were to die of disease in French concentration camps. Several thousand were worked to death in Nazi camps. All of this constitutes what I believe can legitimately be called the Spanish Holocaust. The purpose of this book is to show as far as possible what happened to civilians and why.

Behind the lines, there were two repressions, one in each of the Republican and rebel zones. Although very different, both quantitatively and qualitatively, each claimed tens of thousands of lives, most of them innocent of wrong-doing or even of political activism. The leaders of the rebellion, Generals Mola, Franco and Queipo de Llano, regarded the Spanish proletariat in the same way as they did the Moroccan, as an inferior race that had to be subjugated by sudden, uncompromising violence. Thus, they applied in Spain the exemplary terror they had learned in North Africa by deploying the Spanish Foreign Legion and Moroccan mercenaries, the Regulares, of the colonial army.

Their approval of the grim violence of their men is reflected in Franco’s war diary of 1922 which lovingly describes Moroccan villages destroyed and their defenders decapitated. He delights in recounting how his teenage bugler boy cut off the ear of a captive.[1] Franco himself led twelve legionaries on a raid from which they returned carrying as trophies the bloody heads of twelve tribesmen (harqueños).[2] The decapitation and mutilation of prisoners was common. When General Primo de Rivera visited Morocco in 1926, an entire battalion of the Legion awaited inspection with heads stuck on their bayonets.[3] During the Civil War, terror by the African Army was similarly deployed on the Spanish mainland as the instrument of a coldly conceived project to underpin a future authoritarian regime.

The repression carried out by the military rebels was a carefully planned operation to eliminate, in the words of the director of the coup, Emilio Mola, ‘without scruple or hesitation those who do not think as we do’. In contrast, the repression in the Republican zone was hot-blooded and reactive. Initially, it was a spontaneous and defensive response to the military coup which was subsequently intensified by news brought by refugees of military atrocities and by rebel bombing raids. It is difficult to see how the violence in the Republican zone could have happened without the military coup which effectively removed all of the restraints of civilised society. The collapse of the structures of law and order as a result of the coup thus permitted both an explosion of blind millenarian revenge (the built-in resentment of centuries of oppression) and the irresponsible criminality of those let out of jail or of those individuals never previously daring to give free rein to their instincts. In addition, as in any war, there was the real military necessity of combating the enemy within.

There is no doubt that hostility intensified on both sides as the Civil War progressed, fed by outrage and a desire for revenge as news of what was happening on the other side filtered through. Nevertheless, it is also clear that, from the first moments, there was a level of hatred at work that sprang forth ready-formed from the Army in the North African outpost of Ceuta on the night of 17 July or from the Republican populace on 19 July at the Cuartel de la Montaña in Madrid. The first four chapters of the book aim to explain how those enmities were fomented. They consider the polarisation that ensued from the right’s determination to block the reforming ambitions of the democratic regime established in April 1931, the Second Republic. They focus on the process whereby the obstruction of reform led to an ever more radicalised response by the left. These chapters also analyse the elaboration of rightist theological and racial theories in order to justify the intervention of the military and the extermination of the left.

In the case of the military rebels, a programme of terror and extermination was central to their planning and preparations. The next two chapters describe the ways in which this was implemented as the rebels established control in very different areas. Chapter 5 is concerned with the conquest and purging of Western Andalusia – Huelva, Sevilla, Cádiz, Málaga and Córdoba. Because of the numerical superiority of the landless peasantry, the military plotters believed that the immediate imposition of a reign of terror was crucial. With the use of forces brutalised in the colonial wars in Africa, backed up by local landowners, this process was supervised by General Queipo de Llano. Chapter 6 confronts a similar application of terror in the significantly different regions of Navarra, Galicia, Old Castile and León. These were all deeply conservative areas where the military coup was almost immediately successful. Despite the minimal evidence of left-wing resistance, the repression there, under the overall jurisdiction of General Mola, was of a lesser scale than in the south but disproportionately severe. There is also consideration of the repression in the Canary Islands and Mallorca.

The exterminatory objectives of the rebels, if not their military capacities, found an echo on the extreme left, particularly in the anarchist movement, in rhetoric about the need for ‘purification’ of a corrupt society. Accordingly, chapters 7 and 8 analyse the consequences of the coup within the Republican zone. They consider how the underlying hatreds deriving from misery, hunger and exploitation found their way into the terror in Republican-held areas, particularly in Barcelona and Madrid. Inevitably, the targets were not just the wealthy, the bankers, the industrialists and the landowners who were regarded as the instruments of oppression. No explanation is needed for the fact that hatred was also aimed at the military personnel identified with the revolt. It was directed too, often with greater ferocity, at the clergy who were seen as the cronies of the rich, legitimising injustice while the Church accumulated fabulous wealth. Unlike the systematic repression unleashed by the rebels as an instrument of policy, this random violence took place despite, not because of, the Republican authorities. Indeed, as a result of the efforts of successive Republican governments to re-establish public order, the left-wing repression was restrained and was largely at an end by December 1936.

The exterminatory objectives of the rebels, if not their military capacities, found an echo on the extreme left, particularly in the anarchist movement, in rhetoric about the need for ‘purification’ of a corrupt society. Accordingly, chapters 7 and 8 analyse the consequences of the coup within the Republican zone. They consider how the underlying hatreds deriving from misery, hunger and exploitation found their way into the terror in Republican-held areas, particularly in Barcelona and Madrid. Inevitably, the targets were not just the wealthy, the bankers, the industrialists and the landowners who were regarded as the instruments of oppression. No explanation is needed for the fact that hatred was also aimed at the military personnel identified with the revolt. It was directed too, often with greater ferocity, at the clergy who were seen as the cronies of the rich, legitimising injustice while the Church accumulated fabulous wealth. Unlike the systematic repression unleashed by the rebels as an instrument of policy, this random violence took place despite, not because of, the Republican authorities. Indeed, as a result of the efforts of successive Republican governments to re-establish public order, the left-wing repression was restrained and was largely at an end by December 1936.

The following chapters, 9 and 10, are concerned with two of the bloodiest episodes in the Spanish Civil War, which are closely inter-related. Both concern the siege of Madrid by the rebels and the capital’s defence. Chapter 9 deals with the trail of slaughter left by Franco’s Africanista forces, the so-called ‘Column of Death’ as it travelled from Sevilla to Madrid. It had been announced along the way that the savagery that the column was imposing on conquered towns and villages was what Madrid could expect if surrender was not immediate. The consequence was that, after the departure of the Republican government to Valencia, those responsible for the defence of the city made the decision to evacuate right-wing prisoners, particularly army officers who had sworn to join the rebel forces as soon as they could. Chapter 10 analyses the implementation of that decision, the notorious massacres of right-wingers at Paracuellos on the outskirts of Madrid.

The next two chapters discuss two differing concepts of the war. Chapter 11 is concerned with the Republic’s defence against enemies within. This consisted not just of the burgeoning rebel fifth column, dedicate to spying, sabotage and spreading defeatism and despondency but also the extreme left of the anarchist CNT and the anti-Stalinist POUM. These ultra-left groups were determined to make a priority of revolution. This seriously undermined the Republic’s war effort and thus they were the targets of the same security apparatus which had put a stop to the uncontrolled repression of the first months. Chapter 12 is concerned with Franco’s deliberately ponderous war of annihilation through the Basque Country, Santander, Asturias, Aragón and Catalonia. It demonstrates how his war effort was conceived as an investment in terror which would facilitate the establishment of his dictatorship. Chapter 13 analyses the post-war machinery of trials, executions, prisons and concentration camps which consolidated that investment.

The intention was to ensure that establishment interests would never again be challenged as they had been from 1931 to 1936 by the democratic reforms of the Second Republic. When the clergy justified and the military implemented General Mola’s call for the elimination of ‘those who do not think as we do’, they were not engaged in an intellectual or ethical crusade. The defence of establishment interests was about ‘thinking’ only in so far as progressive liberal and left-wing forces were questioning the central tenets of the right which were summed up in the slogan of the major Catholic party, the CEDA – ‘fatherland, order, religion, family, property, hierarchy’. All of these elements constituted the untouchable elements of social and economic life in Spain before 1931. ‘Fatherland’ meant no challenge to Spanish centralism from the regional nationalisms. ‘Order’ meant no toleration of public protest. ‘Religion’ meant the monopoly of education and religious practice by the Catholic Church. ‘Family’ meant the subservient position of women and the prohibition of divorce. ‘Property’ meant that land ownership must remain unchallenged. ‘Hierarchy’ meant that the existing social order was sacrosanct. To protect all of these tenets, in the areas occupied by the rebels, the immediate victims were not just schoolteachers, Freemasons, liberal doctors and lawyers, intellectuals and trade union leaders – those who might have propagated ideas. The killing also extended to all those who might have been influenced by their ideas: the trade unionists, those who didn’t attend mass, those suspected of voting for the Popular Front and the women who had been given the vote and the right to divorce.

What all this meant in terms of numbers of deaths is still impossible to say with finality although the broad lines are clear. Accordingly, indicative figures are frequently given in the book, drawing on the massive research carried out all over Spain by large numbers of local historians in recent years. However, despite their remarkable achievements, it is still not possible to present definitive figures for the overall number of those killed behind the lines, especially in the rebel zone. The objective should always be, as far as is possible, to base figures for those killed in both zones on the named dead. Thanks to the efforts of the Republican authorities at the time to identify bodies and because of subsequent investigations by the Francoist state, the numbers of those murdered or executed in the Republican zone are known with relative precision. The most reliable recent figure, produced by the foremost expert on the subject, José Luis Ledesma Vera, is of 49,272. However, uncertainty over the scale of the killings in Republican Madrid could see that figure rise.[4] Even for areas where reliable studies exist, new information and excavations of common graves see the numbers being revised constantly albeit within relatively small parameters.[5]

Team of gravediggers working in Víznar (Granada) in 1936. The photo was taken at the farmhouse where the poet Federico García Lorca spent his last hours before being shot on August 19, 1936. The man holding the small girl is Manuel Castilla, aka Manolillo el Comunista, who showed the Irish Hispanist Ian Gibson where he thought Lorca was buried.

In contrast, the calculation of numbers of Republican victims of rebel violence has faced innumerable difficulties. 1965 was the year in which Francoists began to think the unthinkable, that the Caudillo was not immortal, and that preparations had to be made for the future. It was not until 1985 that the Spanish government began to take belated and hesitant action to protect the nation’s archival resources. Millions of documents were lost during those crucial twenty years, including the archives of the single party, the Falange, of provincial police headquarters, of prisons and of the main Francoist local authority, the Civil Governors. Convoys of trucks removed the ‘judicial’ records of the repression. As well as the deliberate destruction of archives, there were also ‘inadvertent’ losses when some town councils sold their archives by the ton as waste paper for recycling.[6]

Serious investigation was not possible until after the death of Franco. When researchers began the task, they were confronted not only with the deliberate destruction of much archival material by the Francoist authorities but also with the fact that many deaths had simply been registered either falsely or not at all. In addition to the concealment of crimes by the dictatorship was the continued fear of witnesses about coming forward and the obstruction of research, especially in the provinces of Old Castile. Archival material has mysteriously disappeared and frequently local officials have refused to permit consultation of the civilian registry.[7]

Many executions by the military rebels were given a veneer of pseudo-legality by trials although they were effectively little different from extra-judicial murder. Death sentences were handed out after procedures lasting minutes in which the accused were not allowed to speak.[8] The deaths of those killed in what the rebels called ‘cleansing and punishment operations’ were given the flimsiest legal justification by being registered as ‘by dint of the application of the declaration of martial law’ (por aplicación del bando de Guerra). This was meant to legalise the summary execution of those who resisted the military take-over. The collateral deaths of many innocent people, unarmed and not offering any resistance, were also registered in this way. Then there were the executions of those registered as killed ‘without trial’ in reference to those who were discovered harbouring a fugitive, and so were shot just on military orders. There was also a systematic effort to conceal what had happened. Prisoners taken far from their hometowns, executed and buried in unmarked mass graves.[9]

Finally, there is the fact that a substantial number of deaths were not registered in any way. This was the case of many of those who fled before Franco’s African columns as they headed from Sevilla to Madrid. As each town or village was occupied, among those killed were refugees from elsewhere. Since they carried no papers, their names or places of origin were unknown. It may never be possible to calculate the exact numbers murdered in the open fields by squads of mounted Falangists and Carlists. It is equally impossible to ascertain the fate of the thousands of refugees from Western Andalusia who died in the exodus after the fall of Málaga in 1937 or those from all over Spain who had taken refuge in Barcelona only to die in the flight to the French border in 1939 or those who committed suicide after waiting in vain for evacuation from the Mediterranean ports.

Nevertheless, the huge amount of research that has been carried out makes it possible to state that, broadly speaking, the repression by the rebels was about three times greater than that which took place in the Republican zone. The currently most reliable, yet still tentative, figure for deaths at the hands of the military rebels and their supporters is 130,199. However, it is unlikely that such deaths were fewer than 150,000 and they could well be more. Some areas have been studied only partially; others hardly at all. In several areas, which spent time in both zones, and for which the figures are known with some precision, the differences between the numbers of deaths at the hands of Republicans or of rebels are shocking. To give some examples, in Badajoz, there were 1,437 victims of the left as against 8,914 victims of the rebels; in Sevilla, 447 victims of the left, 12,507 victims of the rebels; in Cádiz: 97 victims of the left, 3,071 victims of the rebels; and in Huelva: 101 victims of the left, 6,019 victims of the rebels. In places where there was no Republican violence, the figures for rebel killings are almost incredible, Navarra 3,280, La Rioja, 1,977. In most places where the Republican repression was the greater, like Alicante, Girona or Teruel, the differences are in the hundreds.[10] The exception is Madrid. The killings throughout the war when the capital was under Republican control seem to have been nearer three times those carried out after the rebel occupation. However, precise calculation is rendered difficult by the fact that the most frequently quoted figure for the post-war repression in Madrid, of 2,663 deaths, is based on a study of those executed and buried in only one cemetery, the Almudena or Cementerio del Este.[11]

Although exceeded by the violence exercised by the Francoists, the repression in the Republican zone before it was stopped by the Popular Front government was nonetheless horrifying. Its scale and nature necessarily varied, with the highest figures being recorded for Toledo and the anarchist-dominated area from the south of Zaragoza, through Teruel into western Tarragona.[12] In Toledo, 3,152 rightists were killed, of whom 10% were members of the clergy (nearly half of the province’s clergy).[13] In Cuenca, the total deaths were 516 (of whom 36, or 7% of the total killed were priests (nearly a quarter of the province’s clergy).[14] The figure for deaths in Republican Catalonia reached in the exhaustive study by Josep Maria Solé i Sabaté and Joan Vilarroyo i Font was 8,360. This figure corresponds closely to the conclusions reached by a commission created by the Generalitat de Catalunya in 1937 and is thus indicative of the efforts of the Republican authorities to register deaths. Led by a judge, Bertran de Quintana, it investigated all deaths behind the lines in order to instigate measures against those responsible for extra-judicial executions.[15] Such a procedure would have been inconceivable in the rebel zone.

Recent scholarship, not only for Catalonia but also for most of Republican Spain, has dramatically dismantled the propagandistic allegations made by the rebels at the time. On 18 July 1938 in Burgos, Franco himself claimed that 54,000 people had been killed in Catalonia. In the same speech, he alleged that 70,000 had been murdered in Madrid and 20,000 in Valencia. On the same day, he told a reporter there had already been a total of 470,000 murders in the Republican zone.[16] To prove the scale of Republican iniquity to the world, on 26 April 1940, he set up a massive state investigation, the Causa General, ‘to gather trustworthy information’ to ascertain the true scale of the crimes committed in the Republican zone. Denunciation and exaggeration were encouraged. Thus, it came as a desperate disappointment to Franco when, on the basis of the information gathered, and despite a flawed methodology which inflated the numbers, the Causa General concluded that the number of deaths was 85,940. Although exaggerated and including many duplications, this figure was still so far below Franco’s claims that, for over a quarter of a century, it was omitted from editions of the published resumé of the Causa General’s findings.[17]

A central, yet under-estimated, part of the repression carried out by the rebels – the systematic persecution of women – is not susceptible to statistical analysis. Murder, torture and rape were generalised punishments for the gender liberation embraced by many, but not all, liberal and left-wing women during the Republican period. Those who came out of prison alive suffered deep life-long physical and psychological problems. Thousands of others were subjected to rape and other sexual abuses, the humiliation of head shaving and public soiling after the forced ingestion of castor oil. For most Republican women, there were also the terrible economic and psychological problems of having their husbands, fathers, brothers and sons murdered or forced to flee, which often saw the wives themselves arrested in efforts to get them to reveal the whereabouts of their men folk. In contrast, there was relatively little equivalent abuse of women in the Republican zone. That is not to say that it did not take place. The sexual molestation of around one dozen nuns and the deaths of 296, just over 1.3% of the female clergy in Spain is shocking but of a significantly lower order of magnitude than the fate of women in the rebel zone.[18] That is not entirely surprising given that respect for women was built into the Republic’s reforming programme.

The statistical vision of the Spanish holocaust is not only flawed, incomplete and unlikely ever to be complete. It also fails to capture the intense horror that lies behind the numbers. The account that follows includes many stories of individuals, of men, women and children from both sides. It introduces some specific but representative cases of victims and perpetrators from all over the country. It is hoped thereby to convey the suffering unleashed upon their own fellow citizens by the arrogance and brutality of the officers who rose up on 17-July 1936. They provoked war, a war that was unnecessary and whose consequences still reverberate in Spain today.

NOTES

1. Comandante Franco, Diario de una bandera (Madrid: Editorial Pueyo, 1922) p.129, 177.

2. El Correo Gallego, 20 April 1922.

3. José Martín Blázquez, I Helped to Build an Army: Civil War Memoirs of a Spanish Staff Officer (London: Secker & Warburg, 1939) p.302; Herbert R.Southworth, Antifalange: estudio crítico de «Falange en la guerra de España: la Unificación y Hedilla» de Maximiano García Venero (Paris: Ruedo Ibérico, 1967) pp.xxi-xxii; Guillermo Cabanellas, La guerra de los mil días 2 vols (Buenos Aires: Grijalbo, 1973) II, p.792.

4. The most widely accepted figure for Madrid is 8,815. See Santos Juliá, et al., Víctimas de la guerra civil (Madrid: Ediciones Temas de Hoy, 1999) p.412; Mirta Núñez Díaz-Balart, et al., La gran represión. Los años de plomo del franquismo (Barcelona: Flor del Viento, 2009) p.443 and José Luis Ledesma, ‘Una retaguardia al rojo. Las violencias en la zona republicana’ in Espinosa Maestre, Violencia roja y azul, pp.247, 409. The figure of 8,815 is based on that of 5,107 given by General Rafael Casas de la Vega, El terror: Madrid 1936. Investigación histórica y catálogo de víctimas identificadas (Madrid: Editorial Fénix, 1994) pp.247, 311-460, to which, without explanation, 3,708 were added, by Ángel David Martín Rubio, Paz, piedad, perdón… y verdad. La represión en la guerra civil: Una síntesis definitiva (Madrid: Editorial Fénix, 1997) p.316. In the same work pp.317-19, 370, 374, and in, Los mitos de la represión en la guerra civil (Madrid: Grafite Ediciones, 2005) p.82, Martín Rubio gives the figure of 14,898, again without explanation.

5. For examples, see Jesús Vicente Aguirre González, Aquí nunca pasó nada. La Rioja 1936 2 (Logroño: Editorial Ochoa, 2010) p.8, and Francisco Espinosa Maestre in Núñez Díaz-Balart, La gran represión, p.442.

6. Francisco Espinosa Maestre, La justicia de Queipo. (Violencia selectiva y terror fascista en la II División en 1936) Sevilla, Huelva, Cádiz, Córdoba, Málaga y Badajoz (Sevilla: Centro Andaluz del Libro, 2000) pp.13-23.

7. See the chapters on Burgos (by Luis Castro) and Palencia (by Jesús Gutiérrez Flores), in Enrique Berzal de la Rosa, coordinador, Testimonio de voces olvidadas 2 vols (León: Fundación 27 de marzo, 2007) pp.100-102, 217-18.

8. Julián Casanova, Francisco Espinosa, Conxita Mir y Francisco Moreno Gómez, Morir, matar, sobrevivir. La violencia en la dictadura de Franco (Barcelona: Editorial Crítica, 2002), p.21.

9. For analysis of how deaths were registered, see the chapter by José María García Márquez in Antonio Leria, Francisco Eslava & José María García Márquez, La guerra civil en Carmona (Carmona: Ayuntamiento de Carmona, 2008) pp.29-48; Julio Prada Rodríguez, ‘Golpe de Estado y represión franquista en la provincia de Ourense’ in Jesús de Juana, & Julio Prada, coordinadores, Lo que han hecho en Galicia. Violencia política, represión y exilio (1936-1939) (Barcelona: Editorial Crítica, 2007) pp.120-1.

10. Francisco Espinosa Maestre, editor, Violencia roja y azul. España, 1936-1950 (Barcelona: Editorial Crítica, 2010) pp.77-8; Francisco Espinosa Maestre in Mirta Núñez Díaz-Balartet al., La gran represión. Los años de plomo del franquismo (Barcelona: Flor del Viento, 2009) pp.440-2.

11. Mirta Núñez Díaz-Balart & Antonio Rojas Friend, Consejo de guerra. Los fusilamientos en el Madrid de la posguerra (1939-1945) (Madrid: Compañía Literaria, 1997) pp.107-14; Fernando Hernández Holgado, Mujeres encarceladas. La prisión de Ventas: de la República al franquismo, 1931-1941 (Madrid: Marcial Pons, 2003) pp.227-46. Other places of execution are now being studied: http://www.memoriaylibertad.org/.htm.

12. For comparative analysis, see José Luis Ledesma Vera, Los días de llamas de la revolución. Violencia y política en la retaguardia republicana de Zaragoza durante la guerra civil (Zaragoza: Institución Fernando el Católico, 2003) pp.83-4; Ledesma Vera, ‘Qué violencia para qué retaguardia, o la República en guerra de 1936’, Ayer. Revista de Historia Contemporánea, No.76, 2009, pp.83-114.

13. José María Ruiz Alonso, La guerra civil en la provincia de Toledo. Utopía, conflicto y poder en el sur del Tajo (1936-1939) 2 vols (Ciudad Real: Almud, Ediciones de Castilla-La Mancha, 2004) I, pp.283-94.

14. Ana Belén Rodríguez Patiño, La guerra civil en Cuenca (1936-1939) 2 vols (Madrid: Universidad Complutense, 2004) II, pp.122-32.

15. Solé & Villarroya, La repressió a la reraguarda, I, pp.11-12; Josep Benet, Pròleg, Ibid., pp.vi-vii.

16. Francisco Franco Bahamonde, Palabras del Caudillo 19 abril 1937 – 7 diciembre 1942 (Madrid: Ediciones de la Vicesecretaría de Educación Popular, 1943) pp.312, 445.

17. Ramón Salas Larrazábal, Los fusilados en Navarra en la guerra de 1936 (Madrid: Comisión de Navarros en Madrid y Sevilla, 1983) p.13.

18. Antonio Montero Moreno, Historia de la persecución religiosa en España 1936-1939 (Madrid: Biblioteca de Autores Cristianos, 1961) pp.430-4, 762; Gregorio Rodríguez Fernández, El hábito y la cruz. Religiosas asesinadas en la guerra civil española (Madrid: EDIBESA, 2006) pp.594-6.

…This consisted not just of the burgeoning rebel fifth column, dedicate to spying, sabotage and spreading defeatism and despondency but also the extreme left of the anarchist CNT and the anti-Stalinist POUM. These ultra-left groups were determined to make a priority of revolution. This seriously undermined the Republic’s war effort and thus they were the targets of the same security apparatus which had put a stop to the uncontrolled repression of the first months…

I wish to comment on the above quotation from Preston’s article. I am not a specialist although I have read a good deal about conflicts within the Republican zone. According to many sources, the quoted sentence contains or implies several distortions, not least in minimising how persecution of certain leftist groups critically demoralised the republican side. Those familiar with George Orwell’s work can scarcely be unaware of this. Those who study involvement of the communist party and its catch-all use of the label ‘trotskyist’ for any republican whom it wished to murder, will object to Preston’s over-simplification.

I have read several of Preston’s works and he seems to have a tendency to idealise the Republican side. Those of us who deplore the behaviour of both sides think it does no service to the quest for truth to imply that the republicans were whiter than they were, even if the grey is only lightened a shade or two.

[…] especially someone who presumes to review such an important historical study as Paul Preston’s ‘The Spanish Holocaust’, could have written that […]

[…] I saw that Professor Paul Preston would be speaking about his new book, ‘The Spanish Holocaust’, I knew I had to be in the audience. The title of his book is intended ‘to shock and […]

I admire Paul Preston’s work, especially his documenting the ferocity of the Franco regime, but I’m somewhat disheartened by his minimizing of Stalinist repression on the Republican side, including his dismissal of Orwell’s Homage to Catalonia.

[…] […]