Picasso and Delaprée: new discoveries

I would like to add a note on Picasso’s sketch on a copy of Paris-Soir of April 19th, 1937. Since my piece was published in The Volunteer I have come across some new information that links the evidence on Picasso’s initial engagement with the Spanish Civil War at the end of 1936 and in January 1937 to his masterpiece, the Guernica.

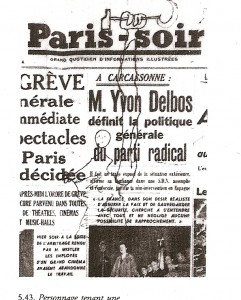

I was especially intrigued by the figure with a raised arm holding a hammer and sickle (image here) that Picasso sketched on a copy of Paris-Soir of April 19, 1937. This not only echoes the Paris-Soir/L’Humanité polemic, it is also highly significant because of its date, just one week before the attack on Guernica. The same image appeared in the sketches that Picasso was drawing as he cast around for a subject for his contribution to the Spanish pavilion at the Paris World’s Fair. The raised arm even makes an appearance in early versions of the Guernica.

Herschel B. Chipp pointed out that Picasso had inked his sketch over an article citing French Foreign Minister Delbos’ wish to have friendly relations with all countries, i.e., including Germany and Italy. However, this did not seem to me to be sufficient–in itself–to spark off Picasso’s indignation. That kind of statement only bothers us when something worse is happening; and in Paris on April 18-19, 1937, as I discovered recently, this was once again the bombing of Madrid.

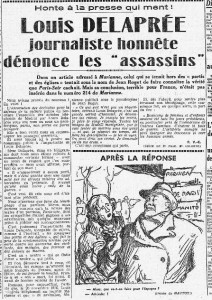

In Paris, a few weeks ago, I studied the microfilm series of Paris-Soir for 1937. On page 3 of this same April 19 issue I saw a startling little item entitled “Madrid was subjected to an extremely violent bombardment yesterday”. This could have been dictated by Delaprée’s ghost, speaking of “pools of blood” on Gran Vía and its sidewalks, and of brain matter being splattered around. But nothing more. Newspapers shared agency and other sources, and this particular news was also published in L’Humanité (19 April, p. 3), and no doubt elsewhere. It is so short and inconclusive as to read like a fragment from a longer text, presumably truncated at source since L’Humanité would not have hesitated to publish it in full. L’Humanité has been digitized and we can consult the corresponding issue here.

If we compare the front pages of the two newspapers we can see that they both highlighted Delbos’ outline of French foreign policy. But there was also a significant difference. Unlike Paris-Soir, L’Humanité also included on its front page the news that Madrid had been bombed, featuring a picture–almost certainly taken from its archives–of destruction to the city.

The contrast is so significant because Picasso was a regular reader of one newspaper (L’Humanité), and had demonstrably handled a copy of the other (Paris-Soir). For L’Humanité readers, then, the news on April 19, 1937 was that the French government was closing its eyes while Madrid was being bombed. This was consistent with L’Humanité‘s overall approach to the war, which repeatedly juxtaposed attacks on the deceit of Non-Intervention with allusions to its nefarious consequences, for example on January 26, 1937 when a photo of rubble and destruction accompanied the headline, “Hitler et le Duce ont répondu”. On the other hand, Paris-Soir had hidden away the bombing of Madrid on an inside page, and was therefore reenacting, albeit on a very small scale, its handling of Delaprée’s reporting in late 1936. So Picasso was not just reacting to what Paris-Soir had printed on its front page, but also to what it had left out.

Picasso’s picture of around April 19, 1937 shows a small figure with an elongated arm–and how often will an arm, severed or otherwise, appear in this story?–ending in a clenched fist and a hammer and sickle. Chipp’s studied this sketch in the Picasso Museum in Paris, and when I briefly inquired about it there two or three years ago, I was told that it might have been transferred to the Reina Sofía Museum in Madrid. I have not pursued this further, and the sketch is not on public display in either museum. But if the complete newspaper, rather than just the front page, has been preserved in the museum archives, then it would be interesting to know if there are traces of additional markings on page 3, where the bombings are mentioned.

At first sight, the significance of the hammer and sickle is only too clear, but as so often in Picasso’s work, things are not quite what they seem. Picasso placed this particular hammer and sickle right at the top center of the newspaper, just above Paris-Soir‘s name. If we look at the issue of L’Humanité for that, or indeed any other day, a hammer and sickle was always at the top, as it formed part of its logo. In his sketch, then, Picasso was impishly transforming an issue of Paris-Soir into L’Humanité, its most bitter enemy. Visually, the joke works well as long as you know that Paris-Soir and L’Humanité had been at odds over the bombing of Madrid ever since Delaprée’s death. As we are talking about a newspaper–and therefore a three-dimensional, social object–perhaps the sketch was done in a café with friends. The background and paper were courtesy of Paris-Soir, so all that Picasso needed was a pen.

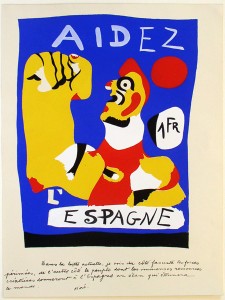

If we are indeed eavesdropping on a shared conversation, rather than studying a conventional “work of art”, then my impression that the character’s right hand is handling, or perhaps inserting letters, between the second “d” and “ée” of the word “décidée” (ie “d….ée”) may not be altogether fanciful. After all, we are, quite unusually, talking about visual annotations to a printed text here. However, the sketch does not need to evoke the dead journalist’s name to link up with the Delaprée affair, as it shares so many other features with it. I imagine that this is not a portrait, as the similarity to Miró’s Catalan/Spanish peasant in “Aidez L’Espagne”, also displaying an enlarged arm, and also from 1937, points in a different direction. The very prominent clenched fist was both the international left-wing and Spanish Republican salute. During the Spanish Civil War it represented defiance and anti-fascist solidarity. Both ideas are presumably present here.

If we are indeed eavesdropping on a shared conversation, rather than studying a conventional “work of art”, then my impression that the character’s right hand is handling, or perhaps inserting letters, between the second “d” and “ée” of the word “décidée” (ie “d….ée”) may not be altogether fanciful. After all, we are, quite unusually, talking about visual annotations to a printed text here. However, the sketch does not need to evoke the dead journalist’s name to link up with the Delaprée affair, as it shares so many other features with it. I imagine that this is not a portrait, as the similarity to Miró’s Catalan/Spanish peasant in “Aidez L’Espagne”, also displaying an enlarged arm, and also from 1937, points in a different direction. The very prominent clenched fist was both the international left-wing and Spanish Republican salute. During the Spanish Civil War it represented defiance and anti-fascist solidarity. Both ideas are presumably present here.

The reason that the bombing of Madrid had become front page news once again was a long forgotten battle that led to the city being heavily shelled for about two weeks after April 10, 1937. Between April 9 and 14, 1937, the Republicans took advantage of the Nationalist campaign in the North to launch a major diversionary offensive to take Mount Garabitas in the Casa de Campo countryside adjoining Madrid, and offer the Republic an anniversary present on April 14. As well as leaving the Francoist enclave in the University City completely exposed, a Republican victory would have ended shelling from the artillery batteries up on the heights. But the Republican failure had the opposite effect: it invited the Nationalists to show that they were still in full command, and hence the intensified shelling.

Several foreign writers were in Madrid at this time. On April 10 Ernest Hemingway, Martha Gellhorn, John Dos Passos and others went to a damaged appartment in the west of the city that Hemingway called “the old homestead”. From there they had a good view of the offensive. The writers also acquired first-hand experience of being shelled, as well as seeing how it affected the city. A page from Virginia Cowles’ diary for April 12, 1937 records “30 dead and 80 wounded from yesterday’s shelling” (facsimile page in Spanish edn, 2011, p. 150). A few days later shelling narrowly missed a British parliamentary delegation. Madrid was heavily shelled on April 22, when the Florida Hotel was hit, forcing Antoine de Saint-Exupéry, Hemingway, Gellhorn, and others out of their bedrooms in their pyjamas.

More important, for our purposes, is that what had happened in Madrid was given considerable attention in France. The bombing of Madrid returned to the front page of L’Humanité, not only on April 19, 1937, but also on April 22 (very briefly), and on April 23. On the 23rd, the previous day’s attack was misleadingly illustrated by a drawing of planes bombing Madrid, whereas the city was actually being shelled from the artillery positions on Mount Garabitas. In fact, the whole point of the shelling was to show how strongly entrenched the Nationalists still were there. But L’Humanité identified the destruction with aerial bombardments by Nazi German and Fascist Italian aviation. The accompanying language was an almost verbatim retake of the language that the newspaper had used on January 9, 1937, at the time that Picasso was beginning Songe et Mensonge: “…Franco fait bombarder Madrid, assassinant femmes et enfants.”

While the intensive shelling of Madrid in April 1937 did not have the savagery of the Condor Legion’s attack on Guernica, it formed a continuum with the earlier, massive aerial bombardments of Madrid. L’Humanité did not have much information when it published a front page article on the destruction of Guernica on April 28, 1937. (A day later it published the famous report by George L. Steer, the London Times journalist.) The best it could do at this stage was show a photo of the victims of previous bombing raids, implicitly Madrid, beneath a large headline on the attack on Guernica. Thus, logically enough, it was past events that initially provided the framework for understanding what might have happened. Allegedly, when the news reached Paris of the bombing of Guernica, the subject was proposed to Picasso and he replied that he didn’t know what a bombed city looked like. If the story is true, then it is marvelously disingenuous, and underlines Picasso’s determination to work on his own terms. Literally, of course, it was quite true. But by late April 1937, Picasso certainly knew a great deal about the impact of bombardments on civilians. He had even been toying with ideas inspired by the shelling of Madrid just the week before. Refracted through the influence of Delaprée’s descriptions of the bombing of Madrid, much of the imaginative groundwork for his masterpiece was already in place.

A very clear pattern emerges as we look at how Spanish news reached Picasso in Paris in the months up to April 1937. Picasso shows no apparent interest in battles or the military vicissitudes of the conflict. But violent death, the bombing of civilians and murderous lies are all present in the series that runs from the painting of 29 December 1936 studied by John Richardson to Songe et Mensonge on January 8-9, 1937 and on to the sketch of April 19, 1937. Many accounts of the genesis of Picasso’s masterpiece describe the destruction of Guernica as unprecedented and wholly unexpected. In the light of what is discussed here, that is misleading. On the contrary, the attack was so deeply disturbing precisely because it was half-feared and half-expected. The destruction of Guernica was a shock in itself, but it also signified that otherwise isolated events were coming together to form an ominous series. Aerial bombardments of other cities, including Barcelona (where Picasso had relatives), were now predictable. And unlike the bombings of Madrid and Durango, which got rather messily mixed up with other news, Guernica was an exceptionally “pure” news event. Thanks to the foreign journalists who covered it, important reports and the first photos were all published in the foreign press over a period of three or four days after April 28, 1937.

It has long been recognized that journalistic reporting and photojournalism worked their way into Picasso’s masterpiece, and indeed may have helped to shape its near monochromatic shading. But the idea that this merely reflected the way Picasso acquired his information may be too benign. The Nationalist claim that the Basques had burnt the city themselves was being widely reported from late April onwards, virtually at the same time as dispatches were arriving on the attack itself. The themes of bombing and lies had already been closely intertwined in Picasso’s reactions to the Delaprée affair, and now there was both a hugely destructive aerial bombardment and the perpetration of a colossal lie. The scratchy newsprint that appears in Picasso’s painting, just above the severed arm, must represent lies as well as news. Manifestly, L’Humanité, too, was far from averse to its own manipulations (cf its drawing on its front page of April 23), which was surely why Delaprée and Steer, both of them independent-minded journalists on center or center-right newspapers, had such an extraordinary influence. Steer provided impeccable, objective reporting, while Delaprée recorded the subjective, emotional experience of living through the nightmare, which I believe fed more directly into the mood of Picasso’s masterpiece.

The deceit of Non-Intervention was wholly discredited by German and Italian aerial bombardments. This was surely why bombings and lies came to be so closely linked together, and not only to Picasso. Very recently, researchers on Latin-American writers and the Spanish Civil War have located a text (1938) by the Ecuadorian Demetrio Aguilera-Malta which imagines Anthony Eden reading the writing of Louis Delaprée and being converted into a ferocious opponent of Non-Intervention (read it here).

In one report, Delaprée himself ended an hour-by-hour chronicle of the bombings in Madrid with the following denunciation (omitted by Paris-Soir): “I am ashamed to be a man when Mankind shows itself capable of perpetrating such massacres of the innocents. Oh old Europe, so bound up in your petty games and your great intrigues, God grant that all this blood does not choke you.”

Picasso recorded his own feelings on a copy of Paris-Soir, dated April 19, 1937, as well as in the infinitely more astonishing and complex masterpiece that was to follow soon afterwards.

(April 2011)

[…] otro trabajo analicé el brazo levantado que sostiene una hoz y un martillo que Picasso dibujó en un ejemplar […]