The Last German Volunteer

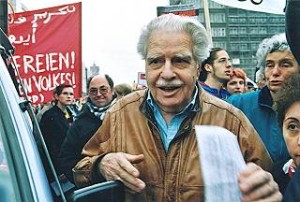

Fritz Teppich, no longer so agile physically at 92, is still mentally active and as cantankerous as ever, especially on three issues, to be mentioned later. But first it must be recorded that Fritz is the last survivor of some 3000 German volunteers who fought against fascism in Spain.

Fritz Teppich, no longer so agile physically at 92, is still mentally active and as cantankerous as ever, especially on three issues, to be mentioned later. But first it must be recorded that Fritz is the last survivor of some 3000 German volunteers who fought against fascism in Spain.

He was one of the youngest. When he arrived in Spain on September 5, 1936 at 17, the International Brigades had not yet been founded; he was never a member but rather a soldier and officer in what became a Spanish-Basque-Catalan unit of the Republican army.

Fritz (as I’ll call him, being an old friend) came from a middle-class Jewish family in Berlin. He first confronted growing anti-Semitism by joining a Zionist boy scout organization but, dissatisfied, he switched to the “Rote Pfadfinder,” the “Red Scouts.” That couldn’t last long. Hitler came to power and his mother, a more far-sighted Cassandra than most, said, “Things are bad and are going to get lots worse!” An older daughter had married the heir to the Kempinski restaurant company and this connection made it possible to send Fritz and one brother to Paris, without their knowing the language and only as apprentice cooks. Fritz survived this rough ordeal for a fourteen-year-old, learned French, and got a job in a luxurious Belgian hotel.

Despite long work days and exhausting toil he kept his eyes on world events, nearly all of them menacing. Fascists were on the attack in the Saarland, in France, Austria, England. He thrilled to see French workers stopping them in Paris and to read how George Dimitroff defied the Nazi leader Goering in a German courtroom. But then came the generals’ putsch in Spain and Fritz knew what he wanted. He slipped away from the hotel one night and made his way alone to the French-Spanish border at Hendaye, just after a bloody battle in which the fascists captured the crossover region. Boarding an overloaded boat, he landed in the Basque republic and the next day, recruited into an anarchist unit and armed with a revolver, he was driven to his first battle station in a big Rolls-Royce left behind by a wealthy Franco supporter. Before long, now in a unit of the United Socialist Youth, he was part of the rear guard battle to save Bilbao and the northern front.

For a while he was stationed on a mountain top with a Swiss-made Oerlikon anti-aircraft cannon, modern, expensive but with a short range of 2500 meters. As the area was still quiet he was able to visit the nearest town and fell in love there with a Basque girl. One day in April, while sitting with the useless weapon, he watched wave after wave of Nazi planes turning the town into a blazing inferno. That was Guernica, whose destruction Pablo Picasso made famous with his painting. This attack, with the bombing of Madrid and other Spanish towns, marked the start of a policy of attacking populated cities.

The Basque country, cut off in the south and barred by British and French blockades from any support by sea, was finally overrun by Franco’s troops and Mussolini and Hitler’s tanks and planes. Fritz is still bitter that no help was received from the Aragon front and its mostly Anarchist units, while the far-left uprising in Barcelona in May 1937 seemed a stab in the back to the Basque defenders. He was one of the last soldiers to escape, once again in an overcrowded fishing boat which landed in France. After immediately returning to Spain he met new International Brigaders in Figueroa but reported back to what was left of his old unit in Barcelona. Now a lieutenant, at 19, he took part in the cold fighting at Teruel. His commander, a highly committed Basque Republican, took him on as a member of his staff (the XXII Army Corps) and in the course of later battles he was promoted several times. He learned Spanish and assumed a Spanish name since, if captured and recognized as a German Communist and Jew, he would have been turned over to the Gestapo.

Franco soon finished the job. Fritz and other officers, not in Madrid, escaped to Alicante to join thousands awaiting the promised British ship to take them to safety. But it was a Franco ship which arrived while Italian troops surrounded them from the land side. Before they could be locked away Fritz saw a chance to slip out but could convince none of his fellow officers to join him. What followed were many weeks of lonely flight, moving by night, hiding by day, only rarely daring to ask for help at farmhouses. Finally, after a risky train trip, he arrived near the same northwestern border crossing where he had once tried to enter Spain–and was betrayed by a pro-Franco mountain dweller.

After months of terrible prison conditions and a constant threat of execution he had an amazing bit of luck. With other prisoners, under heavy guard, he was sent to move beds from a cellar storage site for Moroccan cavalry soldiers accompanying Franco on his visit to San Sebastian. The street was blocked to prevent escape, guards were armed, hostile but lazy. Suddenly a group of women surrounded the group. Defying the guards they threw loaves of bread to the hungry prisoners and, using the Basque language strictly forbidden by Franco, shouted “Adore Lagun!” “Courage, lads!” One woman, close to Fritz, whispered, “The cellar has a back door!”

That was all he needed. He and another prisoner somehow made it to France. With the help of many unknown comrades he returned to Belgium. His stay there, difficult for all refugees, ended within a year when the Nazi army invaded. Like other “enemy aliens” he was loaded in a box car and sent south to France and internment in the infamous prison camp of Le Vernet. Later, as part of a work force of Jewish prisoners, he foresaw the betrayal by the fascist Vichy government , tried, again in vain, to encourage other prisoners to escape with him, and got out just days ahead of the deportation of all of them to Auschwitz.

During a series of daring adventures Fritz, helped by Spanish resistance comrades, was able to get decent clothing and convincing ID papers and crossed back through Spain to Portugal, where he was interned, safe but unable to leave, until the end of the war.

As soon as possible he returned to his home town of Berlin, where, still a Communist, he became a journalist for East German newspapers and their news agency ADN, though living in West Berlin. With his knowledge of languages and many connections in Western Europe he was a valuable contributor. But over the years, his disapproval of some of its leaders, policies and bureaucracy and his sticking to strict principles, aided by a legendary temper, led to a break in the relationship. Fritz was left to his own slim resources in West Berlin.

He never joined in any of the prevalent red-baiting, sharply rejected lucrative offers by the CIA and related institutions and became one of the main organizers of a highly successful peace movement in West Berlin, in which, in good years and difficult ones, he has always remained.

Now Fritz is honored by progressives in Berlin and beyond; in nearby Potsdam a new library of books which the Nazis once burned has been given the name “Fritz Teppich.” Friends and acquaintances are quick to learn of three issues about which he has sharp, decisive views. One is a condemnation of all who hurt the Spanish cause, which includes for him the POUM which revolted in 1937 in Barcelona and which he has accused in several fact-laden booklets of treachery. The second issue is a rejection of all forms of nationalism, definitely including Jewish nationalism, as manifested in the policies of Israel towards the Palestinians. And third, a never-ending anger at the business group which seized control of the Kempinski hotel and restaurant chain during the Nazi years and still controls it, keeping only the well-known name. He succeeded in getting a plaque placed on one main hotel, though far too vague and with no mention of the Jewish workers exploited here before being sent to their deaths. He has lived for many years with his wife Eva near the rail siding from which Berlin’s Jews were sent to their deaths, now a monument. Fritz has never forgotten or forgiven the murder by the Nazis of his mother and younger brother. Nor has he ever lost his allegiance to the “good cause” of oppressed people of every nationality.

(Most material taken from his autobiography: “Der rote Pfadfinder,” Elefanten Press Berlin 1996, ISBN 3-88520-197-6)

Victor Grossman is an American journalist living in Berlin for many years. He published in German a book about the Spanish Civil War, with quotations by volunteers from many countries, Madrid du Wunderbare.