Spaniards and Latinos in the International Brigades

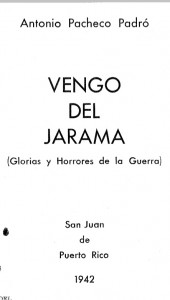

Last year, when Sebastiaan Faber and I tried to identify the black IBer portrayed in a picture by the great photographer Centelles, we came across a great many documents that would help a patient historian tell the relatively unknown story of the US-based volunteers from Spain and from Spanish-speaking America who joined the International Brigades. Even though about 10 per cent of the names on the roster of the Abraham Lincoln Brigade are Hispanic, none of the collections in the ALBA archives belong to any Spanish or Hispanic volunteers, and, somewhat ironically, we know next to nothing about those volunteers for whom the struggle in Spain was particularly immediate. One of the most valuable documents we stumbled across was the 1942 book written by the Puerto Rican journalist Antonio Pacheco Padró, Vengo del Jarama: Glorias y Horrores de la Guerra. The book offers a unique perspective on the International Brigades; I’ll quickly translate a couple of paragraphs to give a sense of the value of the work:

Last year, when Sebastiaan Faber and I tried to identify the black IBer portrayed in a picture by the great photographer Centelles, we came across a great many documents that would help a patient historian tell the relatively unknown story of the US-based volunteers from Spain and from Spanish-speaking America who joined the International Brigades. Even though about 10 per cent of the names on the roster of the Abraham Lincoln Brigade are Hispanic, none of the collections in the ALBA archives belong to any Spanish or Hispanic volunteers, and, somewhat ironically, we know next to nothing about those volunteers for whom the struggle in Spain was particularly immediate. One of the most valuable documents we stumbled across was the 1942 book written by the Puerto Rican journalist Antonio Pacheco Padró, Vengo del Jarama: Glorias y Horrores de la Guerra. The book offers a unique perspective on the International Brigades; I’ll quickly translate a couple of paragraphs to give a sense of the value of the work:

The next day new volunteers arrived to Villanueva de la Jara, among them, several more Cubans and a few Americans and Brits. Among the Cubans, I remember a few: Cueira, who was a baseball player in New York, Captain Corona, Oscar Hernández, Landeta, Arsenio Brunet, Rodolfo de Armas. Several Chileans and Mexicans also arrived from New York, as well as some members from the Spanish Workers Club and the Club Chileno. They were all convinced and valiant antifascists.

Our groups made up the first battalions of the International Brigade, In the convent that served as our headquarters, we organized our battalion, for which was chosen a very American name, Abraham Lincoln. Two compañeros took on the task of making the banner that would fly over the convent, which said: “International Brigade, Lincoln Battalion.” The Battalion had three platoons. One was made up of Cubans, and other Latin Americans, the other Canadian, to which the Irish were added, and the other American, with English and French. At Tom Beckett’s request, I stayed with the Canadian group. I wouldn’t have wanted to be separated from him, as we had become good friends.

With this arrangement, Comrade Royce, an American, assumed the command. I think he was from San Francisco. I had an unpleasant run-in with Royce over my portable typewriteer. One day I came back to the barracks and learned that my typewriter had been taken from my room. I looked all over for it, until I found it in Royce’s office: he had taken it without even notifying me. I wasn’t at all happy about that, and I went to recover my typewriter, ready and willing to fight for it if necesary. Royce would not hand it over and when i grabbed it he blocked the door so that I couldn’t leave. I pushed him and he jumped on top of me. We were about to come to blows when Royce’s assistant, a Jewish American named Markowitz or something like that, came between us, and explained that the typewriter was needed in the Battalion office, and that although they had taken it from my room without my permission, they admitted the error, and were now officially requesting the typewriter. I demanded a receipt, which Royce himself signed, and that was the end of the incident.

That was the first of a series of incidents between “latinos” and “Yanquis” which eventually would lead to our leaving the International Brigade, to join up with the First Mobile Shock Brigade of El Campesino. We broke away from the International Brigade after the Battle of Jarama. Another serious incident took place between Cubans and Americans. In the canteen that was close to the barracks, a comrade from Chicago slapped a Cuban, taking advantage of his larger size and the fact that the Cuban had had a few too many drinks. Soon other Cuban companions arrived and there was a storm of slaps between Cubans and Americans. The Chileans, Mexicans and Puerto Ricans sided with the boys from Cuba and the incident was about to turn into a mutiny. Royce couldn’t control the incident because at that moment there were only two or three companions in the barracks with rifles and bayonets. Besides, he acted with obvious partiality, and if had not been for the diplomatic mediations of the Canadians, things could have turned out very badly. This tense situation lasted the whole time we were in Villanueva de la Jara until we left for the front. When officer were chosen, they were always Americans. The Cubans protested, and two from their group were commissioned: Captain Corona, and Rodolfo de Armas, who was made lieutenant. That’s how the tension was watered down… (pp. 60-61)

That was the first of a series of incidents between “latinos” and “Yanquis” which eventually would lead to our leaving the International Brigade, to join up with the First Mobile Shock Brigade of El Campesino. We broke away from the International Brigade after the Battle of Jarama. Another serious incident took place between Cubans and Americans. In the canteen that was close to the barracks, a comrade from Chicago slapped a Cuban, taking advantage of his larger size and the fact that the Cuban had had a few too many drinks. Soon other Cuban companions arrived and there was a storm of slaps between Cubans and Americans. The Chileans, Mexicans and Puerto Ricans sided with the boys from Cuba and the incident was about to turn into a mutiny. Royce couldn’t control the incident because at that moment there were only two or three companions in the barracks with rifles and bayonets. Besides, he acted with obvious partiality, and if had not been for the diplomatic mediations of the Canadians, things could have turned out very badly. This tense situation lasted the whole time we were in Villanueva de la Jara until we left for the front. When officer were chosen, they were always Americans. The Cubans protested, and two from their group were commissioned: Captain Corona, and Rodolfo de Armas, who was made lieutenant. That’s how the tension was watered down… (pp. 60-61)

[…] manpower in the three Lincoln Companies. Here Merriman says that Company 2 was left in charge of the Cuban named Corona who is described in an article in the Volunteer magazine at the link. Merriman meets with […]

I am the niece of Tom Beckett. I have spent my life learning and looking information about Tom.

Please get in touch with me and tell me what you know, if you were with him in Spain at Jamara and or Albecte.

Thank you.

I believe that Fidel Castro’s July 26th Movement rebels were trained in Mexico by Spanish Republican exiles and possibly International Brigader veterans as well prior to going to Cuba in 1956….

Hello all. We live in an area of Catalonia near the River Ebre, close to the Cardo mountains. We often visit the ruins of a 17th century convent, Sant Hilari de Cardo, that was later used as an International Brigade HQ,then a republican hospital. Just wondering if this could be the convent Antonio Pacheco Padró is referring to.