Collective Memory, A Different Kind of DNA (Teruel, 1938-Derry, 1972)

The morning of the publishing of the Saville Enquiry Report, June 15th 2010, I received an early call, from Elaine Brotherton, a close friend and niece of William McKinney, who was one of the thirteen men who shot dead by the British Army on January 30th 1972. The event became known to the world as Bloody Sunday. Elaine and I have been friends for over thirteen years. We worked together on the exhibition of the Bloody Sunday show, Hidden Truths, which we toured together, It was first shown at Track 16 in Bergamont Station in Santa Monica in 1997 and from there went on to be seen in over twenty venues across the United States. None of it would have happened without Elaine’s tenacity and the support of all the families impacted by Bloody Sunday, in the shadow of the lies of the earlier Widgery Report (issued weeks after the event) and before the Saville Report. But here we were, 38 years after Bloody Sunday, in our different countries, Elaine in San Francisco, myself in Mexico City, both of us linked to Derry—her birthplace and my home for five years in the early 1980’s. We are friends who met through Bloody Sunday.

Elaine was tearful, nervous on the phone, hopeful that the publishing of the Saville Report would allow for both clarity and the possibility of closure, for her, for her family and the other relatives. “In some way I had my closure touring the exhibition,” she told me. “Revisiting the narrative again and again, handling the objects, loaned to us for the show; looking at the massive portrait banners, we shifted from museum to museum.” We remembered on how at moments we felt we were literally traveling with the spirit of these fourteen men (one would die later from his wounds). Each of the families had loaned the exhibition an object, symbolic of their loved one: an old tie, a record album, a golfing trophy. Objects that resonated with the frailty of their pasts. A crumbling rubber sole of a scuffed boot, a petrified candy bar, a notebook in which a teenager had practiced his signature over and over perfecting his style. We would bubble wrap each item carefully, transporting them by hand from venue to venue. Then, in the midst of the tour, came word there would be an enquiry. With it came cynicism, expectation and all the complex emotions of reliving the detailed accounts of what happened that Sunday afternoon.

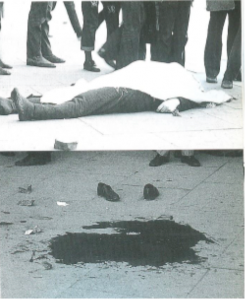

Barney McGuigan’s remains are covered and the blood-stained pavement, Bloody Sunday 1972. Copyright William L. Rukeyser

Elaine was hoping for an end to all the lies and with that closure—a critical closure for the families, but also for a community, an entire people. Fourteen were killed; dozens were wounded; but many more lives were damaged. The lens goes wider still, however: whole communities were impacted, a war began, in which thousands would be killed, and thousands imprisoned. Young people were forced to choose to defend their communities instead of going to college; others even dropped out of school altogether. Often it was not even a matter of choice. For most people there were no choices. No one with a choice, a real choice, would ever choose the gun. Bloody Sunday was a massacre, a crime—but it also marked the beginning of chaos, a time in which there were no choices for the nationalist community. We have choices in times of peace, of prosperity, but not in times of war. For a community that had no vote, no jobs, there were no choices. Bloody Sunday was not the first march; it was one of many.

The Saville Enquiry was critical not only to rectify the lies told about that afternoon; it would also be heard in the context of a new time. It could offer a conclusion to that Sunday afternoon at a new moment: a new generation of teenagers had grown up in Derry, outside the sound of the gun, Hanging on this report were implications which went beyond that day: the events of Bloody Sunday were a watershed in Irish history. Saville had the potential of bringing about more than the truth of that afternoon: a closure to a long overdue open wound.

Living in the Bogside of Derry, in the Rosville Flats ten years after Bloody Sunday, during the aftermath of the Hunger Strike of 1981. I grew up in Ireland. I say grew up because my eyes were opened. I lived amongst the whispers of this massacre that had occurred a decade earlier, which to me seemed, already so long ago. Hard to imagine, just ten years earlier and now suddenly it is 38 years later!

The Bogside in Derry was far from insular in the 1980’s It was somewhat of an international mecca for people passing through . People came to Derry from all over. We flew the Palestinian flag from the Rossville flats during Sabra and Shatila. We were internationalists, we saw ourselves inside a far bigger pictures. We looked east and we looked west and we looked into pasts to make sense of where we were. We heard songs about the Spanish Civil War in Derry. Men from who Derry had gone to fight in Spain. The Irish singer Christie Moore sung about Bobby Sands, but he also sung “Viva La Quinta Brigada” a song about some of the men who left Ireland for Spain: men who joined the Connolly Column organized with Paeder O’Donnell. Then Jo Mulhern, re-sung the song and added other songs, with his band, the People of No Property. They sang of Danny Boyle and Blaser-Brown; of Charlie Donnelly, Liam Tumilson and Jim Straney from the Falls Road; of Jack Nalty, Tommy Patton and Frank Conroy, Jim Foley, Tony Fox and Dick O’Neill, of Frank Ryan Kit Conway, Dinny Coady, Peter Daly, Charlie Regan and Hugh Bonar. Names that lulled us to another place, to another moment another war. But we made the connections, by ideology and desires of freedom. Names that echoed in song around the Bogside on cold nights. Names that belonged to other narratives.

Then there were the names of our own open wounds, names that never left the pavement outside the take-away and the shops in the Rossville Flats, names that lingered on the corner of Chamberlain Street and in the doorways of William Street and Glenfada Park. Names that clung to the architecture, that no amount of scrubbing away of bloody memories could erase, nor attempts at gentrification could make disappear. Even when the flats were demolished as was Rossville, the site of Bloody Sunday, these names have remained etched into the architecture; Patrick Doherty, Gerald Donaghey, Jackie Duddy, Hugh Gilmore, Michael Kelly, Michael McDaid, Kevin McElhinney, Bernard McGuigan, Gerald McKinney, William Mckinney, William Nash, John Young and Jim Wray can still be heard. Elaine began speaking of her Willie, their Willie, just as soon as she could speak. That is where memory goes.

Elaine’s hopeful nervous expectant voice— Derry accent in San Francisco, took me to Rubielos de Mora, not far from Teruel in Spain. A place I had been just three weeks before, a small town in an expansive landscape, where it was hard to imagine harsh winters and treacherous warfare. I had gone to the top of a terraced hillside once farmed now left to natures own devices, where I met Conchi Esteban Vivas and Encarna Martorell—relatives of soldiers from the 84th Battalion, they were, fighting for the Republic, killed there seventy-two years ago. The two women were on a similar mission. Conchi in her dark glasses, full of optimism and emotion, determined that finally she would have the closure her family was seeking. Their relatives had gone missing during the offensive of Teruel. Conchi’s grandfather, Anacleto Esteban Mora fought with the 84th Battalion, and received the same fate as 45 of his comrades. According to Spanish historian Pedro Corral they were shot dead by firing squad by their own officers, led by Andres Nieto. the socialist mayor of Mérida before the war. The great uncle of Encarna, Salvador Martínez Tarazona was also killed. Men who disappeared; who went off to war and never came home, leaving families without explanations—yet these men were not forgotten. Seventy years later their families are still looking for answers.

The mass grave at Rubielos de Mora is the exception rather than the rule. The majority of the 113,000 disappeared in Spain, who lie in unmarked graves were victims of Fascist repression.

The site is treated as a crime scene. The local police have to come to issue a report of these murders before any of the bones can be removed. The archeologists at work here specialize in different areas; they recover bullets. buckles, and buttons; soles of shoes sometimes remain intact, the leather long gone; empty cans of sardines; grenades. Relics of life and death, of war and of survival. .

These disparate events in time and place, these mass killings, perhaps have little in common. Yet what connects them is memory; what connects them are the cover-ups, and the role of the state. Spain and Britain have repressed the memory of these events for their own ends, for political expediency, to obscure the past. Yet in spite of their efforts, people don’t forget. Secrets and pasts and truths are inherited, just as the whispered names cling to the architecture. No amount of cover-ups or state-imposed fear on a nation can suppress the need to remember. Collective memory is a different kind of DNA.

What these Spanish and Irish women share in common is a desire for truth, for dignity and closure. We know where the remains of the fourteen killed on Bloody Sunday are buried, but that is not enough. Before Tuesday, they too had no peace, having gone to their graves cradled in a web of state imposed lies. In Spain, most of these men are lost and their own final narratives unknown. What prevented this dig, and all the others now taking place in Spain, was the power of the state, the complexities of a legacy of fascism, the conditions of the Spanish transition to democracy, which encouraged the country to push the past under the sheets .

This is not about drawing a parallel of narratives for its own sake. What is clear, however, is that what we as people, share in common a need for answers and a need to know the truth about injustices committed, no matter where or how long ago,, in order to move forward from our pasts and heal. This is what links Conchi, Encarna and Elaine, whose lives have been defined until now by unanswered questions, by hidden truths.

This is our humanity. We have the right to our truths. Whether it is Elaine and all the families of Bloody Sunday and their communities or for Conchi and Encarna and the families of over 100,000 people in Spain who lie in unmarked graves.

Moreover, this is not some intellectual exercise of Rashamon. There is no speculation here. We know what happened, we know the injustice and we have always known knew always there were cover-ups. Even today powerful people in both countries resist the investigation of the past. In Spain, as in Britain, there exist conflicting points of view. The rights and dignity of those who represent the truth of the dead, be it seventy or thirty eight years ago. In Spain, the fear of this is enough to remove a Judge from his high office, The Spanish judge, Juez Balthasar Garzón has been suspended for questioning an the country’s 1977 amnesty laws amnesty and to argue arguing for the rights of the voices family members of over 100,000 dead. Their struggle is the same as In Britain, in this case the voices that of the of 14 fourteen families who campaigned tirelessly for thirty-eight years for the right to their truth, not the lies of soldiers covering up a crime.

Prime Minister Cameron stood up in the Houses of Commons on Tuesday June 15th and apologized to the families in Derry for this miscarriage of justice. “It was wrong” he stated. , ”What happened should never, ever have happened, and for that, on behalf of the government – and indeed our country – I am deeply sorry.” Cameron used his age at the time to distance himself from the events. He also stated there had been no cover-up.

To be sure, Cameron was just five, a toddler. But does this mean he carries no responsibility? Elaine was just three but she took on her responsibilities.

None of this would have ever happened had it not been for the families, for their community, for the Nationalist people of Ireland who never let go. No Saville Report would have been issued had it not been for the struggle for a peace process that would genuinely move the people of the island of Ireland forward. This is not about Britain magnanimously putting the score right, but about a people who never stopped demanding the truth. It is their day and their story, and it remains Britain’s shame—apology or no apology.

As Bernadette Devlin McAliskey, wrote in the Guardian on the day after Cameron’s appearance: “Bloody Sunday isn’t just about the families or how the thirteen individuals lost their lives that day; the fourteenth dying later of his wounds. It is about whether the British government committed a war crime in 1972 and in so doing started a war. It is the British government, not their anonymous and brutalized soldiers of their alphabet army who should be in the dock, at the international court of justice at The Hague. If Saville has closed that route to truth and justice, the British government will consider it worth every penny.”

In Spain, it is often women who are the custodians of memory, who campaign and organize these archeological digs, who contact the archeologists and make it happen. Women so often the custodians of our pasts, of memories

“Is it possible to have peace and reconciliation while the old guard remains in power?” asked Peter Pringle, journalist and author who has written on Bloody Sunday and whose notebooks became critical in the evidence of the Saville Report. If we look across Europe to Spain, and the so-called “Ley de Memoria,” or Memory Law, what do we learn from this understanding of pasts? We see new faces on the old guard, still there, still powerful and its implications not only on the work of one judge, an individual l but on a legacy of war, without which there can be no closure or peace.

I think of Conchi and Encarna digging in the earth; the density of the turf, hard work in the relentless heat and sun, of the blisters on hands from spades, of the sheer physical effort of their digging for answer’s, not necessarily found or revealed on the first search. Perhaps Conchi’s and Encarna’s digging has only just begun. I think of Elaine, and her relatives, marching each January from the Creggan shops down the back road to the Bogside, the route of the original march and the bitter cold wind chaffing at the skin; and in between the marching, the years of campaigning, and the organization and I think of her blisters and the collective blisters of the families and a community, a people who never stopped marching.

Elaine was three when her Uncle William McKinney was murdered. Conchi and Encarna would not be born for another forty after their grandfathers and uncle were shot and their bodies dumped somewhere on a hillside outside Rubielos de Mora, Teruel. For these women, these men and their stories have defined a significant part of who they are.

These are different times, different languages spoken, causes and lives—and yet the desire for truth is the same. So is the need for peace and closure, whether one knew the warmth or breath or laughter of the uncle, grandfather, father, brother, sister, mother, or not. What we learn is within all this our identities run deep and to be alive and at peace. We all need truth, whether our governments like it or not.

June 20 2010 copyright Trisha Ziff

Trisha Ziff is a filmmaker and curator of photography living in Mexico City. Currently directing the documentary, La Maleta Mexicana / The Mexican Suitcase, she was the curator of the exhibition Hidden Truths Bloody Sunday. She lived in the Rossville Flats in Derry, from 1982 to 1986.

Yes Tricia, it was a long wait.

-Bill Rukeyser

I wonder if Ms Ziff’s use of the word ‘murder’ is quite justified. According to Corral, these soldiers (ten men from each company of the 84th chosen by lot) were shot for rejecting an order to return to the front: in effect ‘desertion in the face of the enemy’. The fact that the same men had only just been withdrawn after some 10 days of fighting in the bloodied ruins of Teruel in sub-zero temperatures and with virtually zero supplies of food and ammo. was irrelevant. The same fate could easily have been meted out to British and N. American survivors at Brunete. The same fate WAS meted out to thousands of Russians at Stalingrad.

beautiful article. thanks for sharing it!

great work!

free mary jane!

I welcome and commend the tenacity and endurance of all who persevered for so long under most difficult circumstances which eventually brought about the Saville Report findings. Were it not for the people like Elaine and many others who refused to be silenced, Saville may well have ended up just like Widgery. The British were forced to tall some of the truth, but not all. They got away light.

Well done, Cameron’s apology is your legacy.

I was in Derry during the ’80s, hanging out with the Nelis family and witnessing the international atmosphere of solidarity among international political visitors! Recently at an ALBA workshop I recounted how many Derry folks were ready to go support Argentina in the Falklands and that at night, after last orders, the song that was sung was The Internationale and Viva La Quinta Brigada. Everyone in the Castle or Dungloe bar knew every word,