The Singing Dutchman of the Lincoln Brigade

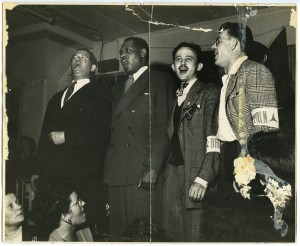

Bart van der Schelling, Paul Robeson, Moe Fishman, and Art Landis. Tamiment Library, NYU, ALBA Photo 66, box 1, folder 3.

(Editor’s note: This article comes with sound files. To listen to the segments, simply click the “Play” button.)

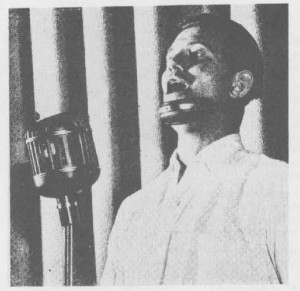

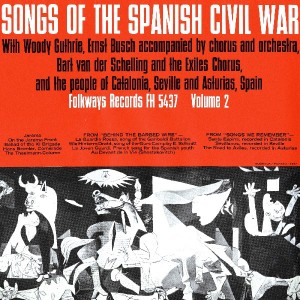

Alongside Pete Seeger, Woody Guthrie, and Ernst Busch on the cover of the legendary Songs of the Spanish Civil War (1961-62) stands a lesser known name: Bart van der Schelling. The liner notes don’t tell much about him. They include a photo of the man in front of a 1930s microphone, singing; one can’t help notice the heavy metal brace under his chin. They also reveal that he was born in Rotterdam in 1892 and fought in Spain with the Lincoln Brigade. More intriguing is the fact that the text credits van der Schelling with the lyrics to Viva la Quince Brigada. Inspired by an old Spanish folk tune, the song was made famous in the English-speaking world by Seeger and the Almanac singers. It’s never overlooked at a reunion of the Lincoln veterans.

Who was this Dutch singer and lyricist? How did he end up in the company of Seeger and Guthrie? Why is he unknown today, even in his home country?

An internet search did not lead to any van der Schelling songs but to a painting offered for auction from the estate of Elaine de Kooning, late wife of the painter Willem de Kooning. Like Bart, de Kooning came from Rotterdam. Another click brought me to A Gathering of Fugitives, a memoir by author Diana Anhalt who tells the story of left-wing Americans who lived in Mexico during the 1940s and ‘50s to escape anti-Communist campaigns. They were a lively and eccentric bunch that, in addition to a good number of Hollywood directors and scriptwriters, included Bart van der Schelling and his American wife Edna Moore.

Anhalt’s book offers a slightly more of Bart’s biography:

Dutch-born Bart van der Schelling had been a circus clown, a political visionary, an opera singer, and an officer in the International Brigades during the Spanish Civil War. Fearing deportation from the United States, he arrived in Mexico in 1950, where he tuned pianos for a living until a heart attack forced him to retire. Although more than 50 at the time, he started painting, achieving some recognition as a primitive artist.

Bart with jaw brace. From the liner notes of the second Spanish Civil War album by Smithsonian’s Folkways Records.

Anhalt’s main source was Bart’s widow, Edna, whom she interviewed in the 1990s. Having grown up in Mexico City, Anhalt met Bart as a young girl. I managed to track her down, and she, in turn, put me in touch with others who knew Bart when they were children. They were smitten with him. “He was a hero of my childhood,” says Linda Oppen. “I think all of us in the exiled group in Mexico rather worshiped him, as a romantic figure and standard-bearer of good causes.” Everyone who knew Bart recalls him singing, always and everywhere. Particularly memorable was his booming version of “Freiheit,” also known as “Die Thälmann-Kolonne.” Although U.S. political persecution reached into Mexico, causing Bart’s wife Edna to lose her job at the American School, it appears their time in Mexico was a happy one.

This positive impression was confirmed when I located a cache of Bart’s personal documents, letters to his youngest sister in the Netherlands, written a few years before his death in 1970. After a series of heart attacks, the deficient state of Mexican health care forced Bart and Edna to return to the United States. He hated it. The Vietnam war infuriated him and nostalgia for Mexico wells up in every letter.

Bartholomeus van der Schelling was born in 1892 into a Rotterdam family with socialist sympathies. His father was a stucco worker, and several brothers worked at the slaughterhouse on the same street the family lived. Two of van der Schelling’s nieces informed me that life in the Boezemstraat was poverty-ridden. “The floor was bare—yet there was a piano, and everyone could sing.” Bart left for the U.S. in 1927, leaving behind his wife and two young children. It was a domestic drama: he never got in touch again and, as far as his nieces know, he never paid a cent of alimony. “Bart went out for cigarettes and never returned,” one of his nieces sneered.

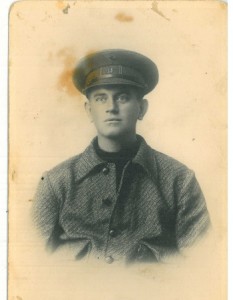

One niece showed a photo of Bart wearing the International Brigades uniform. “I guess there must have been some contact between Bart and his brother Huib, my father,” she concludes. She remembers a stack of Bart’s letters that she threw out. Just as she threw out the painting that Bart had given to his brother 1964. “I didn’t like it,” she says with a loud laugh. Another niece kept her painting as well as letters that Bart sent to his sister between 1964 and 1970. They are touching notes from an old man who longs for family he hasn’t seen in many years. “Life for the van der Schelling family was none too rosy as far as material things were concerned,” he wrote in late 1967, “yet there was a deeply felt love among us, and that helped a whole lot.” His letters deal with the day-to-day. He talks about his intense contentment when UNICEF selects one of his paintings for their annual set of holiday cards, his many ailments, and the high cost of medical care.

In Willem de Kooning. An American Master (2004), authors Mark Stevens and Annalyn Swan mention van der Schelling as one of De Kooning’s closest friends. Yet they provide little information about that friendship. De Kooning arrived in the States in 1926 as a stow-away and moved into the Dutch Seaman’s Home in Hoboken. Bart, who left a couple of months later, must have met Willem there. From then until the late 1930s Bart and “Bill”—as de Kooning called himself—“spent so much time together so often they seemed like brothers,” the biographers report. About van der Schelling they write: “Well known for never keeping a job or having any money, Bart was big, charming, and exceedingly attractive to both men and women.”

De Kooning worked as a house painter; Bart looked for singing gigs. Together they moved to Manhattan, where Willem found jobs as a set builder and Bart performed in musicals. Willem met Nini Diaz, with whom he maintained a relationship until World War II. Nini’s family worked in the circus, which likely explains the story about Bart as a clown. Bart’s name reappears in de Kooning’s biography in the early 1930s, when the painter rented a summer home in Woodstock, a well-known artists’ colony. “Bart…was the cook and I took care of the house,” Nini told the biographers. “We had the front room. And we had a ball.”

Then the economic crisis hit. Both de Kooning and van der Schelling were close friends with Robert Jonas, who in 1933 helped found The Unemployed Artists’ Union, headquartered near Union Square in Manhattan. Naturally, the union leaned left. Jonas was a member of the Communist Party but de Kooning was not. “They never stopped talking, him and Jonas,” Nini Diaz recalled. “All about communism. And when they were finished, they just started in again.” Bart was more interested in politics than Willem. He was Jonas’s roommate and Jonas’s influence on him seems to have been much stronger than on de Kooning. Their shared circle included Max Margulis, a journalist for the Communist Daily Worker, as well as Max Vogel, a German-born architect.

Bart volunteered for Spain: “I was told not to bring anybody to the docks when the ship was about to sail. They wanted to make it as inconspicable as possible. An old friend of mine, by the name of Max Vogel, he drove me to the docks, and I went aboard ship. So that I looked like a traveler, I had bought in a second-hand store on Second Avenue a very fine Gladstone bag, and behold, it had on it a lot of tickets, you know, let us say from the Orient Express, and all places in Europe. It was very impressive.” Disguised as a tourist, van der Schelling left New York early in 1937 to join the International Brigades.

Bart recorded the story of his departure from New York: on a set of crackling, hissing reel-to-reel tapes that no one had played in years. I found them among the ALBA collection at the Tamiment Library. But they had not been transcribed and were too fragile to play. They had to be digitized. When the CDs arrived, I loaded one into my computer and suddenly I heard Bart—an old voice speaking English with an unmistakable Dutch accent.

His story starts in the fall of 1936, almost randomly and without introduction. There must have been other tapes covering the years before. Bart tells us he performed in a musical, Professor Mamlock, written at a time when “the star of Hitler was on the rise and unfortunate to say 95 percent of the German population followed Hitler’s star.” At night, Bart would join his friends Jonas and de Kooning in a café where the “revolutionists” gathered. A lot of talk, but little action, he concluded.

“By that time nobody knew I had made up my mind and made arrangements to go to Spain and enlist in the International Brigades,” he says. He doesn’t explain why he made that decision. He does allude to problems: he calls himself “an uninvited guest” in the United States. “I was a Hollander who also was not exactly welcome in his own country,” he adds, without giving any details. Yet somehow he managed to get a passport from the Dutch embassy and he left for Spain.

Bart (second row, third from the bottom) at a dinner of the Veterans of the Abraham Lincoln Brigade. Date unknown. (Click on the picture for a larger view.)

The years from 1937 until the early 1940s are rich with detail. Bart describes the voyage to France; crossing the Pyrenees; his years in Spain, serious battlefield injuries and anger at being declared unfit for action mid-1938, after which he continued the struggle as interpreter. He recalls the train journey back to France with other injured soldiers, whom he cheered by singing battle songs; and finally his return to the United States as a stow-away. Then, halfway through 1940s, his story stops as abruptly as it had started.

Bart is a laconic, factual narrator. Rarely, if ever, does his voice reveal emotion, not even when he recounts the moment he ended up in a shell hole on the hard Spanish soil, critically injured. His head was out of the reach of enemy fire but his long Dutch legs were not, and were repeatedly hit until he was rescued by a brave fellow Brigader. On another occasion, he was riding in a lorry as it was bombed by Italian planes. The car flew off the mountain road—“all I remember seeing is that large valley, and then nothing.” He woke up days later in the hospital with a neck injury, which would not be properly treated until his return to New York. The incident earned him the unmistakable chin brace in the picture on the Folkways liner notes.

Bart’s voice betrays some despair when he tells how inexperienced and untrained the American volunteers were. He was in his mid-40s and had experience through his military service. He tried to instill discipline in his fellow Brigaders. They called him grandpa, which he accepted good-naturedly. Without irony he tells the story of his close friend Paul Block, a sculptor from Ohio, who left for the front with a backpack containing heavy books—including Marx’s Capital. “I said: Listen, Paul, you are not going to kill the fascists by throwing Das Kapital at them. Take your rations and throw those books away.”

(Block would die from wounds at Belchite.) The International Brigades’ ideological drive was considerably stronger than their military expertise; to make things worse, the enemy was better armed. Bart tells how they would spend weeks waiting for ammunition “that, to make a long story short, we never got.”

Many American veterans remember Bart singing—all the time and everywhere. “Seems like only yesterday that we were swinging thru Tarazona’s timberland to the cadence of Bart’s thundering “We are the fi—ting antifassists,” Ed Lending wrote to Edna. Bart explains that, when he woke up in the hospital after the lorry accident, he first asked about his knapsack which contained his notes of Spanish folk tunes and other songs in many languages that the IB-ers sang. One day in Barcelona, shortly before his evacuation, he witnessed the funeral of 40 miners who had died in a bombardment. Els Segadors, the Catalan anthem was played which made an unforgettable impression on Bart. The song would become a fixture in the repertoire with which he would leave audiences across the United States in awe. The Tamiment tapes also feature Bart singing. They are recordings from 1966. His voice seems to have lost some of the force it must have had, but his fierceness is undiminished:

Many American veterans remember Bart singing—all the time and everywhere. “Seems like only yesterday that we were swinging thru Tarazona’s timberland to the cadence of Bart’s thundering “We are the fi—ting antifassists,” Ed Lending wrote to Edna. Bart explains that, when he woke up in the hospital after the lorry accident, he first asked about his knapsack which contained his notes of Spanish folk tunes and other songs in many languages that the IB-ers sang. One day in Barcelona, shortly before his evacuation, he witnessed the funeral of 40 miners who had died in a bombardment. Els Segadors, the Catalan anthem was played which made an unforgettable impression on Bart. The song would become a fixture in the repertoire with which he would leave audiences across the United States in awe. The Tamiment tapes also feature Bart singing. They are recordings from 1966. His voice seems to have lost some of the force it must have had, but his fierceness is undiminished:

Bart’s illegal return to the United States must have occurred sometime during 1939. He doesn´t mention dates, nor does he explain why he decided to return to New York. His file in the Rotterdam municipal archive contains a note indicating he tried to reapply for a Dutch passport, which he had apparently lost in Spain. In any case, he wasn’t the only one among the American volunteers to return to the U.S. clandestinely. Lincoln vets, often wounded, were helped by the crews on passenger lines, where they would be stowed away in small spaces below the engine rooms. Bart recalls the cold, and the fact that he was handicapped by his tall Dutch physique. “I couldn´t stretch out my legs, and my legs had all the wounds. I got kind of goofy, I guess, and saw all kinds of things moving.”

A Greek comrade had joined him on the trip back. Once they got to New York, the trick was to pretend to be regular sailors going out for a night on the town. Bart made it through, but his Greek friend was stopped and sent back to Europe. Bart was paranoid and started walking. After a while to took a cab. “The taxi driver dropped me off at Times Square. I noticed that people were looking at me.” He stopped in front of a shop window with mirrors. “I looked at myself and saw what was the matter. My eyes were very bloodshot and my hair was sticking up like clay. I had a terrific big raincoat, but I had Spanish sandals. I looked like Frankenstein.” At one point Bart ran into someone he knew: “He couldn´t believe his eyes. He took me to his house and from there I went to the house of my friends Robert Jonas and Willem de Kooning.”

To make ends meet, Bart depended on the support of Friends of the Abraham Lincoln Brigade. He even made a trip to Ernest Hemingway’s house in Florida. When he met Hemingway in Spain, Papa had promised to help Bart in whatever way he could, “if we both survive this.” Hemingway kept his word, and got Bart a job on a friend’s boat.

Just before the audio tape ends, and Bart’s recounting the 1940s, he tells how Willem de Kooning helped him get his U.S. papers by arranging a fake marriage to an American woman. “Eleanor, my wife to be,” are the last audible words. After that, nothing but crackling and hiss.

The ALBA collection offered another pleasant surprise: an interview with Edna Moore, the American woman who Bart met in Los Angeles in 1944. Edna is interviewed by Manny Harriman, a Lincoln vet who videotaped his former comrades. By then Bart had died. Edna is a petite, slender woman, carefully made-up and quite lively. Edna met Bart through music. An enthusiastic amateur pianist, she was asked by a friend to sit in on a performance by Bart at a psychiatric institution where, it later turned out, Eleanor was being treated. From Edna’s stories it is clear that even though Bart had married Eleanor to get his papers, he did not abandon his second wife.

Following his doctor’s advice, Bart moved to California to escape the New York cold. In her interview, Edna frequently apologizes for what she does not know. Still, her account fills important gaps. She explains, for example, that in the 1930s Bart had joined the cast of Show Boat, the hugely successful musical in which Paul Robeson sang “Ol’ Man River.” Robeson wasn’t allowed into the white actors’ dressing rooms, Edna says. This kind of blatant injustice drove Bart raving mad.

In 1940 Bart recorded an album for the League of American Writers, Behind the Barbed Wire, to raise money for European writers suffering from Nazi persecution. From that moment he would regularly perform at Writers League meetings. He also met up-and-coming folk singers. A 1942 headline in the New York Times read “Sizzlers against Nazis”: “Men fight for their liberties with songs on their tongues as well as with guns, tanks and planes.” It was a story covering a show by the Almanac Singers, including Woody Guthrie. “Most moving,” the Times reported, “was the group called Verboten. Bart van der Schelling sang ‘Peat Bog Soldiers’ (Lied der Moorsoldaten), the poignant song of the men in the concentration camps.”

Edna and Bart moved in together soon after they met. Until 1950 they would host weekly hootenannies or music parties. Pete Seeger was among the regulars. But then the trouble started. Friends warned them that the FBI was watching them. Later it turned out that this was the case for many “premature antifascists” who had defended the Spanish Republic. Bart and Edna sought refuge in Mexico, where they ended up in a milieu that fit them well: displaced American leftists, writers, Hollywood directors, Mexican artists. Initially, Bart made a living tuning pianos, while Edna worked at the American School. Later, Bart had a short stint teaching at the conservatory of music.

Midway through the 1950s Bart started having health problems and had to stop working. Edna encouraged him to take up drawing. He quickly developed into a succesful naïf painter. It was his art that gave him the opportunity to return to the Netherlands for a 1964 exhibit at the Schiedams Museum. It was the first time in almost 40 years that he saw his ex-wife and children. There was no reconciliation.

“He was like a Dutch Woody Guthrie,” recalls Jim Kahn, son of the blacklisted screenwriter Gordon Kahn. “He was always comfortable where he went, he learned the local ways, he could adapt. I never had the feeling he wanted to go back to a former life. He was always moving forward. He was very charismatic. A gentle giant.”

In 1965, Bart and Edna returned to the United States because Mexican medical care was insufficient. By then he had reinitiated contact with his youngest sister. Shortly before his death, he wrote: “Dear, dear Nellie, I would give anything to be with you all. There’s a saying that says: blood is thicker than water. This is what I feel as time moves on and I know that I will not see you anymore before the man with the scythe shows up.”

Bart died in October 1970.

My thanks to Toby-Anne Berenberg, the daughter of Fredericka Martin, who served as a nurse in Spain and did important work to document the activities of the medical volunteers and other vets, including Bart van der Schelling. Dutch versions of this text were first published in De Groene Amsterdammer and broadcast on Dutch national radio (podcast).

Yvonne Scholten is a Dutch writer and freelance journalist who has worked as a foreign correspondent in Italy and other countries. English version by Sebastiaan Faber.

What an extraordinary article–an article, which I hope, will be a prelude to a book. Those of us who had the good fortune to have known Bart, were reminded of his extraordinary good nature, his sense of humor, his ability to adapt. (As a child, I was drawn to him by his interest in whatever I had to say.)

Am just delighted this fine article has seen the light of day, and, although I am not familiar with the original, I think is was well-translated, well written. I do hope it–and others– will appear elsewhere and that Yvonne Scholten will receive the recognition she deserves for this ambitious work.

Very interesting, After so many years a dutch comrade becomes finally known.

Ms Scholten has given us an exceptional gift in writing this biography of Bart van der Schelling. The translation is superb. I hope it will be widely read. Bart was a gallant and heroic figure and those of us who knew him will never forget him.

After reading Yvonne Scholtens book on Fanny Schoonheit (an absolute pageturner and good source of information about the so called intrahistoria of the spanish civil war) I am looking forward to her next book, on Bart van der Schelling.

I am truly glad to glance at this website posts which contains

plenty of useful facts, thanks for providing such information.

Ahaa, its pleasant discussion on the topic of this article at this place at this web site, I have read all that, so at this time me also commenting here.

Volume one is hard to find.

Incidentaly if you are in Aberdeen, go visit the Bob Cooney house foot of the main street-Union streetat the beach end at the Castlegate.

He fought against the murdererous Franco supporting fascists in Spain in the late 30,s.

I was a student to Tobyanne Berenberg Martin in junio high school, in Mexico City. She was such a passionate teacher and showed us how four school walls would teach us nothing about the real world.

Glad to found this website with this interesting information about a moving life. I know him from the song “Wie hinterm Draht” in german. It is so historic that so many men and women from different countries came to Spain to fought for democracy. Nowadays a little of that come back, when there is a new fight for it in Ukraine. Just without the social Utopien Visions of Bart and his comrades.