The Right to Bury One’s Mother: Filmmakers Almudena Carracedo and Robert Bahar on Franco’s Victims’ Quest for Justice

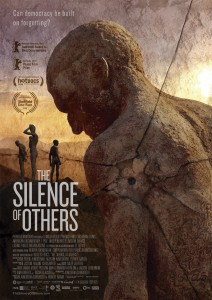

After seven years of work, a new PBS documentary on the international quest to bring Francoist officials to justice is making the festival rounds. An interview with the filmmakers.

When I visited Almudena Carracedo and Robert Bahar in their Madrid apartment last November, they seemed prey to a peculiar mix of exhaustion, expectation, and anticipated nostalgia.

After six years of filming and a year of editing, they were putting the final touches on The Silence of Others, their gripping 90-minute documentary on the fate of a group of Spanish citizens whose parents were disappeared by Francoist forces, whose newborn children were taken away from them, or who were imprisoned and tortured by the regime. In 2010, after the Spanish courts refused to take on their cases—citing the 1977 Amnesty Law—the plaintiffs resorted to an Argentine court in an attempt bring Francoist officials to justice. A veteran Argentine judge, María Servini, decided to take on their case under the umbrella of universal jurisdiction. The “Argentine Lawsuit” (in Spanish, la querella argentina) has been ongoing since.

Although the conservative Spanish government has done its best to stymie Servini’s efforts to interrogate and extradite more than a dozen former Francoist officials, the case has seen some important victories. In 2014, Servini ordered the exhumation of a mass grave in Guadalajara, Spain, thought to contain the remains of Timoteo Mendieta, the father of one of the plaintiffs. Mendieta, a union leader, was shot shortly after the Civil War. Although the first exhumation was unsuccessful, a second attempt in 2017 succeeded in recovering Mendieta’s remains. The exhumation process was widely covered by Spanish and international media. It is also the final chapter of Carracedo and Bahar’s film.

At the time of my November visit, the filmmakers were nervously awaiting news from the festival circuit. The suspense was hard to bear, they admitted, given the intense competition for major festivals like Sundance or Berlin. To top things off, they had also begun saying goodbye to their Spanish home of seven years. Whatever happened to this film, the next phase would mean abandoning the sunlit apartment in which they’d raised their young daughter—who is about the same age as this project—and possibly moving back to the United States. (Carracedo is Spanish; Bahar is American.) Their previous project, the Emmy-award-winning Made in L.A., chronicles the organizing efforts of immigrant workers in the Los Angeles garment industry and took five years to film. Both films were produced for PBS’s acclaimed Point of View (POV) documentary series.

When we speak again, five months later, Carracedo and Bahar are still in Madrid, and still exhausted—but the suspense has made room for elation. They have just returned from Toronto, where they presented The Silence of Others to an enthusiastic crowd at the Hot Docs festival, the film’s North-American premiere. (It was named one of the Top 10 Audience Favorites.) Toronto was their fourth festival screening in three months. The world premiere, at the Berlinale in February, garnered them no fewer than two prizes: the Peace Film Prize and the Panorama Audience Award. (Ever the team, Bahar and Carracedo regularly finish each other’s replies.)

“Although the story makes you think, it appeals to the heart first.”

Tell me about the reception of the film so far.

Carracedo: “It’s been incredibly moving. We’ve realized our film is an emotional experience even more than an intellectual one. Although the story makes you think, it appeals to the heart first. Young audiences have been especially receptive.”

Bahar: “They completely get it. They understand the parallels. One of the things that struck the people at PBS about the film was actually the way our story runs parallel to the debate about the confederate monuments in the U.S. South. In that sense, it was quite symbolic that the film had its world premiere in Berlin. Germany, after all, has taken clear steps to address difficult questions from the past—through its education systems, its museums—even in its policies on public speech. Screening this film in Berlin actually helped highlight the complete lack of measures toward truth, justice, reparations and guarantees of non-repetition in Spain.”

What audiences does your film speak to?

Bahar: “Beyond people who want to know about Spain specifically, we are getting a lot of interest from other societies that are dealing with legacies of conflict—from Algeria and Lebanon to Sri Lanka, Colombia, and the Balkans. What this reflects, I think, is the fact that this story—tragically—is not unique. In the end, the questions that conflict leaves society with are similar everywhere: What do we remember? What do we forget? Who is entitled to justice? Who isn’t?”

Carracedo: “In fact, we initially thought we were going to have to make two different versions of the film: one for Spain, and one for non-Spanish audiences. At one point we realized we could do with one version. Now that we’re screening the film, this has become crystal clear. For one thing, in Spain, too, people know very little about this history. We go deep into things that still have not really been discussed widely.”

Bahar: “At Hot Docs in Toronto, an audience member identified herself as the daughter of a member of the International Brigades. One of the main characters in our film, Chato Galante, was there, too. (A student in the last years of the Franco regime, Galante was arrested and tortured by the Spanish police. His torturer, who was nicknamed ‘Billy the Kid,’ was never tried and continues to live in Madrid, not far from Chato. The Argentine court has requested his extradition for interrogation, but the Spanish authorities have refused to grant that request—SF.) When Chato met the daughter at the screening, he teared up and publicly thanked the Brigades.”

Carracedo: “He said: ‘The International Brigades are the best that humankind has given the world.’”

Have audience reactions surprised you?

Carracedo: “Yes. We expected positive reactions from people who are politically aligned with the cause. But we also worked very hard to edit the film so that it would appeal to anyone, whether they knew about the issues or not, and whatever their political leanings, especially in Spain. That seems to have worked. I’ve had Spanish people come up to me after the screening, saying: ‘You have changed me.’ That’s amazing to hear, of course. Another surprising thing is that audiences are finding the film hopeful. And that’s not artificial. We do believe that things are changing, and we wanted the film to be positioned exactly in this cultural moment in Spain, where change finally seems possible.”

“Change finally seems possible in Spain.”

You followed the Spaniards who filed the Argentine Lawsuit over six years’ time. Did you think about the way in which your long-term presence in their lives helped shape their experience, or even change the story itself? Of course, now that the film is being screened, it’s even more likely to be a catalyst…

Carracedo: “Our previous film, Made in L.A., took five years to film. And there, too, we had to ask ourselves what it means to give a voice to people who would otherwise remain voiceless. In the Spanish case, this was actually a less complicated question. After all, we were filming people who had already decided to break the silence and become agents instead of mere victims. Still, when you appear with a camera you give people a sense of value. That’s incredibly beautiful. One of the elderly women we follow in the film, María Martín, whose mother was disappeared during the Civil War and left in an unmarked mass grave, has a daughter who wasn’t initially too interested in the cause. It took her a long time to understand what her role might be. In the end, she took over for her mother—and our filming played a role in that process. Another one of our characters, who was present at the premiere in Berlin, told us: ‘Finally, we exist. We exist for the whole world to see.’”

Bahar: “Think about the objectives of the victims, who have become organizers and plaintiffs. What they are fighting for is truth, justice, reparations, and guarantees of non-repetition. All of these goals imply breaking the silence. Being in the film also helps accomplish some of those objectives. For one, it helps get the truth out. And to the extent that recognition is a form of reparation—recognition of one’s status as a victim, recognition that a crime took place—the act of making a film is a piece of a justice process as well. Of course we hope that the film—as it’s seen by wider audience, including lawmakers—eventually will help catalyze some of the other pieces, too.”

Remarkably, your film has been reviewed positively in Spain across the political spectrum—even by right-of-center newspapers like El País and El Mundo. This may show that public opinion on the issue of historical memory is continuing to shift or normalize. But I think these reviews are also a testimony to the careful way in which your film tells its story. It doesn’t immediately push buttons in a politically conservative audience. What’s remarkable is that you manage to walk this line without depoliticizing your film.

Carracedo: “We made an effort to include some of the narratives in Spain that argue against revisiting the past. For example, in one scene the son of one of our protagonists says he is not in favor of changing street names that remember Francoist officials.”

“Spanish history is a battlefield.”

I noticed that in the brief interludes where you give the historical background, the voice-over is Almudena speaking in the first-person plural, as “we” Spaniards…

Carracedo: “Writing that text in the first person plural was very difficult. I wanted to say enough for people to understand the story, without having some audience members shut down. We were totally aware of the fact that Spanish history is a battlefield. We realized that the best way to tell the story was through individuals. That’s why we decided to limit the voice-over sections and to humanize the characters as much as possible—convincing the audience that this is not about taking sides, or about the narratives that you’ve learned in school or through your family. This is about real human beings. After you sit down with someone like María Martín, who visits her mother’s unmarked grave at the side of a highway every day, will you be able to tell her that she does not have the right to bury her mother? Because once you meet someone and get to know their story, the whole master narrative collapses.”

Bahar: “There’s another important point here. The decision to make a film about the Argentine Lawsuit is a decision to make a film about something that happens in the present day. This not a film about something that should have happened in 1938, or about decisions that should have been made differently in the Spanish Transition. No, it’s a film that fundamentally focuses on one question. It is 2018. The victims are in this situation—”

Carracedo: “—So what do we do?”

Bahar: “Yeah.”

Carracedo: “Staying in the present was very useful to escape the cliché of the Spanish historical memory film. Our film is not historical. It merely uses history to understand the present.”

Bahar: “This is also a bold way to sweep aside the arguments that are often used to throw up obstacles in this road to justice. Because when you take away those historical arguments, and say—”

Carracedo: “—Okay, fine, that’s what happened—”

Bahar: “—History was what it was—”

Carracedo: “—But what do we do today?”

The Silence of Others will screen in both New York and Washington, D.C. in June. It will have two screenings at the Human Rights Watch Film Festival in New York City, with characters and filmmakers in attendance at both: Tuesday, June 19th at 18:30h (Film Society of Lincoln Center’s Elinor Bunin Munroe Film Center); Wednesday, June 20th at 21:00 (IFC Center). Details are available at https://ff.hrw.org/film/silence-others?city=New%20York

It will also have two screenings at the AFI Docs Film Festival in Washington, D.C. with one of the filmmakers in attendance: Saturday, June 16 at 12noon at the AFI Silver Theater in Silver Spring, MD and Sunday, June 17 at the E-Street Cinema in Washington, D.C. Details are available at https://www.goelevent.com/AFIDocs/e/TheSilenceofOthers

The film will also be part of the lineup for Impugning Impunity, ALBA’s Human Rights Film Festival. (New York City, September 21-23.)

The Silence of Others

A film by Almudena Carracedo and Robert Bahar

The Silence of Others reveals the epic struggle of victims of Spain’s 40-year dictatorship under General Franco, who continue to seek justice to this day. Filmed over six years, the film follows the survivors as they organize the groundbreaking “Argentine Lawsuit” and fight a state-imposed amnesia of crimes against humanity, and explores a country still divided four decades into democracy. Seven years in the making, The Silence of Others is the second documentary feature by Emmy-winning filmmakers Almudena Carracedo and Robert Bahar (Made in L.A.). It is being Executive Produced by Pedro Almodóvar, Agustín Almodóvar, and Esther García.

Festival selections: Berlin International Film Festival; International Film Festival and Forum on Human Rights of Geneva; Moscow International Film Festival; Hot Docs: Canadian International Documentary Festival; Millennium Docs against Gravity Film Festival; Transilvania International Film Festival (Romania); Oslo Pix (Norway); Sheffield Doc/Fest Sheffield International Documentary Festival; Human Rights Watch Film Festival New York; AFI Docs (Washington DC, US)

La Querella Argentina / The Argentine Lawsuit

La Querella Argentina / The Argentine Lawsuit

In 2010 a group of Spanish citizens, organized in several groups, decided to press charges against former representatives of the Franco regime before an Argentine court. Judge María Servini de Cubría is overseeing a trial looking into the imprisonments, tortures, murders, and disappearances—classifiable as crimes against humanity—that took place during the Spanish Civil War and resulting dictatorship. Those bringing the lawsuit had tried to seek justice in the Spanish courts, but ran into the 1977 Amnesty Law; the same law that the Spanish government has been brandishing in its multiple refusals to grant Servini’s requests for extradition of the suspects.

International pressure on Spain to repeal the Amnesty Law has been increasing. For several years now, the UN Committee on Human Rights has been criticizing the Spanish State for failing to comply with the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, which Spain ratified forty years ago. The Amnesty Law “hinders the investigation of past human rights violations, particularly crimes of torture, enforced disappearance and summary execution,” the UN Committee stated in the summer of 2015. In the Committee’s mind, the responsibilities of the Spanish State are clear. It should “actively encourage investigations into all past human rights violations”; ensure that “the perpetrators are identified, prosecuted, and punished in a manner commensurate with the gravity of the crimes committed”; and “implement the recommendations of the Committee on Enforced Disappearances.” This latter body recommended in December 2013 that Spain investigate all cases of enforced disappearance “regardless of the time that has elapsed since they took place,” prosecute any suspected perpetrators, and provide reparations for the victims—revoking or changing the Amnesty Law to make that possible.

The daughter in the story would be me. It is an excellent film. I tried not to cry.