Ferdinand in his 80s: Still No One Knows Why He Smells the Flowers

When it first came out, The Story of Ferdinand was not greeted as the simple story that Munro Leaf claimed to have written. With the Spanish Civil War raging, the book seemed to be an obvious allegory. But of what?

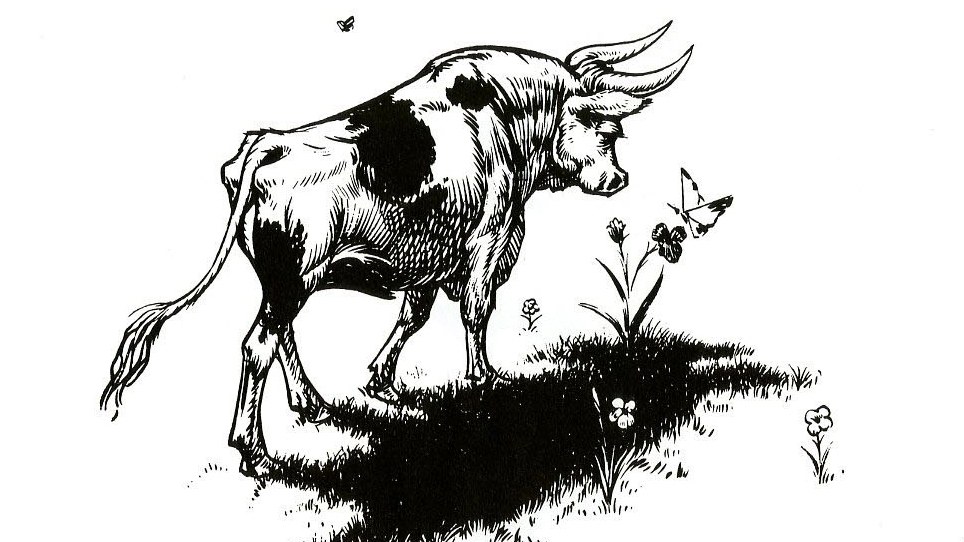

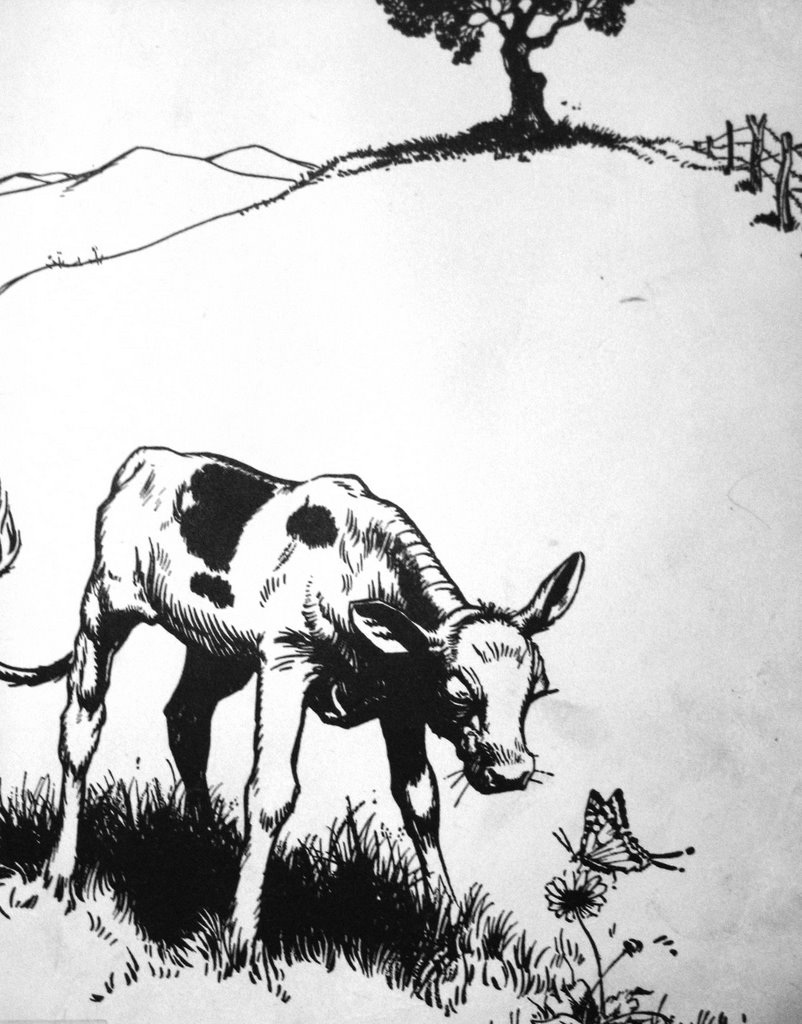

In December 2017, when 20th Century Fox released an updated version of Munro Leaf’s classic children’s book, The Story of Ferdinand, attention returned not just to the Spanish bull who preferred to sit under his cork tree and smell flowers rather than fight in the ring, but also to the turbulent moment of its release in September 1936. With the Spanish Civil War then three months old, Leaf’s book was not greeted as the simple story that Leaf always claimed to have written. Instead, the book elicited a wide range of responses. It was condemned, celebrated, berated, and beloved, with all of these reactions either bespeaking or belying the book’s immense popularity with adults and children that has always marked Ferdinand’s reception. By the end of 1938, The Story of Ferdinand was outselling Gone with the Wind. Ferdinand had appeared as a balloon in the Macy’s Thanksgiving Day Parade and had marched on a float (ironically?) in the Rose Parade in Pasadena, CA. The book, illustrated by Leaf’s friend and collaborator, Robert Lawson, had been remade as a Disney animated short film, which then, in turn, won an Oscar. But, by the 1940s, Ferdinand had also been banned in Franco’s Spain, reputedly burned by the Nazis in Germany, celebrated by Mahatma Gandhi and Franklin and Eleanor Roosevelt among others, and characterized elsewhere either as pacifist twaddle or as “red propaganda” and, for good measure, as a pro-Fascist allegory of one person “who wants his own way and gets it.” (New Yorker, Talk of the Town, 1938).

By the end of 1938, The Story of Ferdinand was outselling Gone with the Wind

Of course, the weight of these many different readings rested on a relatively light foundation. The Story of Ferdinand totaled just 800 words. Leaf always claimed to have composed the book in forty minutes one Sunday afternoon in October 1935 after his wife, Margaret, begged him to leave her alone so she could finish her own work reading a book manuscript for a publisher. Ferdinand’s character never offers why he prefers flowers to fighting. He just does. When his mother asks him why he stays under his cork tree while the other bulls knock heads with each other, Ferdinand responds simply if not enigmatically: “I like it better here where I can sit just quietly and smell the flowers.” So, perhaps Munro Leaf did give the reader who sought causation in their plots a lot of room to maneuver.

And one did not have to look far. The world outside the shade of Ferdinand’s favorite cork tree was brimming a slew of causative factors, politics and war. With the Civil War raging and the November 1936 Battle of Madrid on the verge of starting, Leaf’s story, set in Spain and about a meek and gentle bull, seemed to be an obvious allegory. But, of what? Troops were massing. Bombs were falling. International Brigaders were arriving in Spain. The great contest of ideologies, Democracy, Communism and Fascism was exploding, and yet, here was the biggest, strongest bull in the herd whiling away the day sniffing flowers. Was Ferdinand’s refusal to fight part of a broader celebration of pacifism? Was Leaf ruminating on the events transpiring in Spain at all? Or, was it a call for continued isolationism for the United States? After all, Ferdinand just wanted to be left alone and not fight other people’s fights. Was it a call for steadfast individualism and independence? Other reactions proved that this big, strong bull contained multitudes. Newspaper letter writers around the US claimed that Leaf’s book was creating “mollycoddles” of their sons. A woman’s group in New York in 1937 condemned the book as an “unworthy satire of the peace movement.”* Others implied that Ferdinand’s message was ultimately one opposed to peace movements. Ferdinand does not intercede in the affairs of the other bulls and he seems to take no position about whether the other bulls should fight.

A woman’s group in New York in 1937 condemned the book as an “unworthy satire of the peace movement.”

Munro Leaf always appeared befuddled by these disparate readings of The Story of Ferdinand. He no doubt enjoyed the fruits of the multi-sided appeal and profound popular success. The book has now sold millions of copies. Ferdinand has appeared in movies, toys, clothing, even jewelry. Yet, when it came to the multiplicity of meanings, Leaf always appeared weary: “As far as I am concerned,” he said once in an interview, “there is one story there — the words are simple and quite short. They try to make sense and if there is a message in them, as many people seem to want, it is Ferdinand’s message, not mine — get it from him according to your need.”

And readers have. In 1951, Ernest Hemingway wrote a short story ostensibly to counter Ferdinand entitled The Faithful Bull. Here in the opening paragraph of the story, one might glean what Hemingway felt was missing from Leaf’s version of bull-fighting:

One time there was a bull and his name was not Ferdinand and he cared nothing for flowers. He loved to fight and he fought with all the other bulls of his own age, or any age, and he was a champion…

And here, after the bull not named Ferdinand has fought bravely and died in the ring, the story leads the dead bull out of the ring:

“…Qué toro más bravo,” the matador said as he handed his sword to his sword handler. He handed it with the hilt up and the blade dripping with the blood from the heart of the brave bull who no longer had any problems of any kind and was being dragged out of the ring by four horses.

Sixty years later, the story still generates a wide range of readings. Pamela Paul, writing in 2011 on the 75th anniversary of the book, said, “It’s not a stretch to think of Ferdinand as more than just a symbol of peace, but as an icon for the outsider and the bullied.” Even the 2017 film version of The Story of Ferdinand, now simply Ferdinand, renders the animal as an adorable family pet, a bull of great strength and power who is a sensitive and fun soul who needs just “to be himself.”

An historian’s mission is to chart the changes in these kinds of images over time. The historian’s assumption is also that the way in which a character is read and reproduced over time always speaks more to the context of the reader than it does of the character. While Ferdinand could not escape being read as an allegory of Spain, as a rumination of the conflict that raged when the book appeared in 1936, Ferdinand was also a protean enough figure to accommodate any number of interpretations. Perhaps this protean quality reflected Leaf’s own character. Always speaking to more than one audience, intentionally or not, seemed to be one trait that Leaf carried with him. A year after the publication of the book, Munro Leaf spoke to an audience of mostly children and their parents at the New York Times National Book Fair in November 1937. Awaiting a chance to laugh at the exploits of Ferdinand, the hundreds of children in the audience were instead offered an opportunity to hear Leaf bemoan one criticism he personally received that called the book a “celebration of the laissez-faire theory of economics seconded by the bourgeois ideology of utility.” According to the Times, the loudest laughs came from the children in the audience.

* Among the many recent works on The Story of Ferdinand, one good summation that is more deeply researched than most, and the source of some of the examples here, is Bruce Handy, “How the ‘The Story of Ferdinand’ Became Fodder for the Cultural Wars of its Era,” in The New Yorker (15 December 2017).

Joshua Goode is The Volunteer’s book review editor. He teaches at Claremont Graduate University.

My parents read me the story when it first came out in 1936. It’s a great book with a simple message: Peace is better than war; gentleness trumps violence; smelling the flowers is a much finer activity than allowing them to whither and die. The greatness of Ferdinand is in its simplicity. All other so-called analysis and search for the story’s “meaning” is a bunch of bull.