Bob Smillie and the Memory of the P.O.U.M.

The fate of the POUM, among the most controversial episodes of the Spanish Civil War, is shrouded in taboo. Founded by Andreu Nin and Joaquín Maurín, the Partido Obrero de Unificación Marxista (Workers’ Party of Marxist Unification) fought alongside the Republic, defending the workers’ revolution as the road to society’s emancipation. After the so-called Barcelona May Days of 1937, however, the POUM, along with other Anarchist groups, was persecuted and outlawed by the Republican government, which even banned the circulation of its newspaper, La Batalla. The POUM leadership was arrested, imprisoned and, in some cases, killed, triggering one of the darkest moments of the Spanish Civil War on the Republican side. Among those who died was Bob Smillie, an international volunteer from Scotland affiliated with the Independent Labour Party.

The ILP Contingent in Spain

The Independent Labour Party (ILP) was one of several foreign contingents that provided assistance to the militias of the POUM before the official creation of the International Brigades. Founded in the UK in 1893 by Union Leaders of socialist affiliation, the ILP’s relationship with the Labour Party was tense from the outset. In 1931, the ILP refused to accept Labour’s electoral program and ran for elections without Labour’s official support. They won five seats, allowing them to create their own parliamentary group.

The ILP took part in the Spanish revolution alongside the POUM, sending a small group of volunteers of diverse backgrounds that ended up including the writer George Orwell. This initial contingent was forged around the figure of John McNair, a delegate of the party in Barcelona and an important point of reference for its members. It also included Irish volunteers such as Paddy Donovan or Patrick O’Hara; volunteers from Wales and the United States; and women: Sybil Wingate began as McNair’s secretary before becoming a nurse and a miliciana on the Huesca front. Together, they made up a centuria—a formation of approximately 100 men—led by Georges Kopp.

Bob Smillie

A special figure in the ILP contingent was Robert Ramsay “Bob” Smillie. Born in Larkhall, Scotland, in 1916, Smillie belonged to a family with a long working-class tradition: his grandfather was the famous mining unionist Robert Smillie, one of the ILP’s founders. Bob became intensely involved in the workers’ struggle, officially joining the ILP in 1935 and quickly becoming part of the Guild of Youth organization. In 1936, he arrived in Spain as McNair’s assistant, but soon after requested to go to the war front. It was there that he met George Orwell, who bore witness to Smillie’s courage in Homage to Catalonia.

Smillie died in Spain under mysterious circumstances. The fact that the truth about his death still has not been established is due in part to the lack of clarity of the Republic’s institutions. We know that in the wake of the Barcelona May Days, at the height of the POUM’s persecution by Republican authorities, Smillie was arrested in Figueres, north of Barcelona, when he was about to cross the French border. He was charged with traveling with war material, as he was apparently carrying some empty grenades. He was transferred to Barcelona and from there to Valencia, where he remained officially confined in the Model Prison awaiting trial, accused of rebellion.

While his comrades of the POUM and delegates of the ILP in Spain tried to visit him in jail and resolve the situation, the authorities unexpectedly reported that Smillie had died of appendicitis or peritonitis during his transfer from the Valencia prison to the Provincial Hospital in the same city. Smillie was buried hurriedly in Valencia, on June 12, 1937. His comrades and political representatives at the ILP were notified after the fact. Because noone was allowed to see the body, rumors surrounding his death began spreading quickly.

Some members of the ILP, among them David Murray, accepted the authorities’ official conclusion that Smillie had died of natural causes. Other comrades and witnesses were convinced that he had been another victim of the Stalinist purge. Strong statements in support of this theory came from Ethel McDonald, a Scottish anarchist who provided English-language coverage of the war through the CNT’s radio station in Barcelona, and who was herself arrested in the wake of the May Days.

Georges Kopp wrote an account of Smillie’s death in which he mentioned another witness: the German anarchist Gustav Doster, member of the DAS (Deutsche AnarchoSyndikalisten), an organization that had been operative in Barcelona since 1934. Doster, too, was captured after the May Days, along with other German anarchists, and transferred to Valencia. Sometime later, he assured Kopp that he had been imprisoned with Smillie. Curiously, there is clear evidence that Doster was in fact held at the checa of Santa Úrsula, one of the centers of the Soviet secret police (GPU) in the city of Valencia, located a few minutes from the Provincial Hospital (which is now a Municipal Library). The Valencia lawyer Francisco Pérez Verdú, who was in charge of keeping the files of the foreign prisoners detained in those years, gives a good account of the situation.

Did Smillie die of natural causes while being transferred from the Valencia Model Prison to the hospital, or did he pass through—and possibly die at—the checa? Strangely, historians who have tried to clear up the mystery surrounding Smillie’s death, such as John Newsinger and Tom Buchanan, have not consulted contemporary Spanish sources, including the testimony by Pérez Verdú. Similarly, Daniel Gray’s Homage to Caledonia: Scotland and the Spanish Civil War doesn’t cite Spanish sources on the May Days and their consequences, which include the arrest of the POUMistas. (Gray does mention the dispute between Murray and Smillie’s father, who in 1938 accused Murray of hiding crucial information about the death of his son.) Even those who accepted the official account that Smillie died of appendicitis never inquired about the location of the Scotsman’s grave. As we know, Smillie’s death is not the only episode left unresolved; so is the disappearance of Andreu Nin.

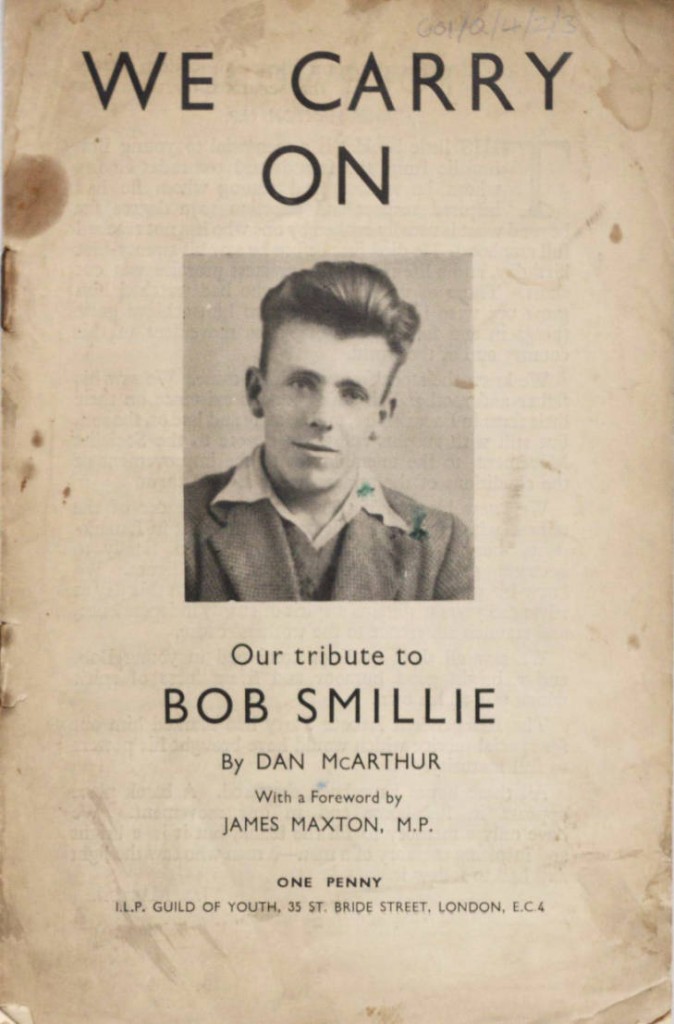

Memory

Smillie’s memory lives on in books like We Carry On: Our Tribute to Bob Smillie, by Dan McArthur, with a foreword by James Maxton. It’s one in several works that aim to recover the memory of the POUM and its allies, focused mainly on clarifying the causes of their persecution. Further research on this period would be a good thing, helping to explain perhaps the development of the Spanish left since 1978—including its persistent divisions, which have surfaced in the recent conflict over self-determination and independence in Catalonia. Unveiling the mysteries surrounding the disappearance and death of figures such as Andreu Nin or Bob Smillie may lay the foundation for a fraternal gathering of the different forces that make up the left. Only then will we be able to focus on fighting the common enemy—fascism. Antifascism, after all, is not just a political position. First and foremost, it will always be a humanist position.

Postscript: On November 14, I was able to locate Bob Smillie’s grave at the Valencia cemetery, thanks to the invaluable help of the city government. More to follow soon.

Mairéad Hache is a writer and activist. She published in La Directa and Nueva Cultura and is coordinator of the traveling exhibit “Espacios de memoria: las Brigadas Internacionales.” This article is dedicated to the memory of Robert Ramsay “Bob” Smillie.

This is a great discovery for the History of Spain that has been silenced to all of us. Moreover, it contributes to honor the memory of Bob Smillie.

All my admiration for the author of this discovery, Mairéad Hache, who has solved many doubts and has found the final whereabouts of Bob.

I want you to know that, for me and for many people, you have become the family that Bob would have wanted to have. Congratulations for your efforts and your true feelings. Bob Smillie will be very proud of you. In fact, I’m sure he is.

Kind regards.

Well done, Mairead!!!!

Hello Mairead, I am an independent researcher in Scotland, interested in Bob Smillie ever since I read about him in ‘Homage to Catalonia’. I was very interested to read that you had located Bob Smillie’s grave. I went to the Valencia cemetery looking for it, last year, with the plot number Tom Buchanan gave me (he had got it from Smillie’s family members in Australia). The plot that I was looking for did not exist – the place where it should have been was devoted to large family mausoleums – and I was told by the cemetery manager that bodies in that area had been sent to an ossuary. It would be great to hear more from you about this! Best wishes, Hilary

[…] su muerte pero todavía no sabe dónde está su cuerpo. Puede que fuera quemado. Ha publicado un artículo en la revista de la Brigada Lincoln y están promoviendo un homenaje en Valencia en […]

Estimado Manuel Aguilera: Gracias por tu comentario. Te escribo en relación a lo que comentas sobre el fallecimiento y el lugar de entierro. Bob Smillie está enterrado en el Cementerio General de Valencia, la tumba está perfectamente localizada y no es cierto que el cuerpo fuese quemado. De igual forma, el rumor acerca de que fue enterrado bajo nombre belga tampoco es cierto. Esto último fue difundido principalmente por publicaciones de Ethel McDonald. En este sentido, quería aclarar que toda esta información con sus respectivos informes se encuentra ya oficialmente registrada en la Orwell Society.

Dear Mr Horrocks: Thank you so much for your comment. Yes, the location of the burial site it is perfectly located. He was buried in a mass grave of the lates ’30s. This mass grave was “opened” lately in 1948 but only one body (of another person) was removed. Some years ago, several pantheons were built in the area, but there are no official records about any removal. This means that the bodies still remain there. This info was provided by the Historical Archives of the Cemetery. If you need further info, please let me know.

Dear Alan and Teresa: Thank you so much! 🙂