Pete and the Feds: Seeger’s FBI file reveals Lincoln connections

Pete Seeger entertaining Eleanor Roosevelt (center), honored guest at a racially integrated Valentine’s Day party marking the opening of a Canteen of the United Federal Labor, CIO, in then-segregated Washington, D.C. Photographed by Joseph Horne for the Office of War Information, 13 Feb. 1944. Public domain.

“Even a superficial reading of an article written by a Communist or a conversation with one will probably reveal the use of some of the following expressions,” warned a 1955 pamphlet published by the U.S. First Army Headquarters that aimed to teach its readers “How to Spot a Communist.” The expressions that were a dead give-away? “Integrative thinking, vanguard, comrade, hootenanny, chauvinism, book-burning, syncretistic faith, bourgeois-nationalism, jingoism, colonialism, hooliganism, ruling class, progressive, demagogy, dialectical, witch-hunt, reactionary, exploitation, oppressive, materialist.” The one word that doesn’t seem to belong in this list of hardcore political vocabulary is the playful hootenanny. What on earth can be Communist about folk musicians getting together for a jam? Still, we can guess who was most likely responsible for its inclusion: none other than Pete Seeger. After all, it was Seeger and Woody Guthrie who, in the early 1940s, popularized the hootenanny; and it was they—with the Almanac Singers, the Weavers, and as solo performers—who became the embodiment of political folk in the United States, paving the way for the generations of Bob Dylan, Arlo Guthrie, and Ani DiFranco.

J. Edgar Hoover was convinced: musicians could not be trusted. As it turns out, the Feds had their eyes on Pete Seeger for over 30 years, yielding an almost 1,800-page file. The Bureau “kept trying to tie him to the Communist Party,” writes Mother Jones’s David Corn, who got his hands on the dossier through a Freedom of Information request, “and the first investigation in the file illustrates the absurd excesses of the paranoid security establishment of that era.” In fact, what alerted the FBI to the young Seeger was a protest letter he wrote as a recently drafted soldier in 1943. “I felt shocked, outraged, and disgusted,” he wrote, “to read that the California American Legion voted to 1) deport all Japanese after the war, citizen or not, 2) Bar all Japanese descendants from citizenship!! We, who may have to give our lives in this great struggle—we’re fighting precisely to free the world of such Hitlerism, such narrow jingoism.” At the time Seeger was engaged to Toshi Ohta, whom he would marry the same year, and whose father was Japanese.

From the moment the FBI had him in the cross hairs—reading his mail and tapping his phone—Seeger did little to allay their suspicions. There wasn’t a progressive cause, from antifascism and pacifism to labor unions and civil rights, that he didn’t support with his signature, his donations and, most often, his banjo. As early as the fall of 1940, he had performed at a Chicago caucus of the American Peace Mobilization, the successor of the American League for Peace and Democracy (formerly Against War and Fascism). Starting in 1940 or 1941, he toured the country with the Almanac Singers (Millard Lampell and Lee Hays in addition to Seeger and Guthrie), playing at union halls, strikes, and public protests. In August 1948 he founded The Weavers, with Hays, Ronnie Gilbert, and Fred Hellerman. A year later, when Seeger along with Paul Robeson was scheduled to perform near Peekskill, New York, in a benefit for the Harlem chapter of the Civil Rights Congress, the concertgoers were attacked by a group from the Veterans of Foreign Wars armed with baseball bats and rocks.

Naturally, Seeger’s lifelong connection with the veterans of the Abraham Lincoln Brigade did not ease FBI suspicions. Strangely, the FBI seems to have missed the fact that Seeger recorded the Songs of the Lincoln Brigade in 1944 for Moe Asch’s label, with Tom Glazer, Bess Lomax, and Baldwin Hawes, while on a weekend’s furlough. Still, Lincoln Vets appear throughout the file. As a soldier stationed in Biloxi, Mississippi, Pete was friends with former Spanish Civil War volunteer and fellow soldier Nick De Mas. In April 1942, the Almanac Singers performed at a meeting of the Japanese American Committee for Democracy, where Lincoln vet Bart van der Schelling also spoke. (“In many instances,” the FBI agents noted with concern, “white and colored people arrived together and apparently were close friends.”) In 1947, The Volunteer carried an ad for Seeger’s records. In April 1949, he sang Spanish Civil War songs at an event for the Joint Anti-Fascist Refugee Appeal Committee where VALB members spoke against the inclusion of Franco Spain in NATO. In May 1949, Lincoln vet Bob Reed wrote in the Daily Worker that Pete’s May Day performance had been a smashing success. In 1950, when Seeger was part of a Robeson concert for the victims of the Peekskill riots, the VALB were in charge of security. In May 1953, Seeger played at a dinner of the Committee to Defend Steve Nelson. In December 1954, the Seeger family sent a postcard to John Gates and other U.S. Communist leaders who had been indicted and imprisoned under the Smith Act. In February 1962, he performed for a gathering of the vets. In fact, Seeger was a fixture at the vets’ annual reunions ever since his 1944 album of Civil War songs “was played through loudspeakers for 500 guests at the VALB reunion in New York City that same year,” as Peter Glazer recalled in these pages. “As long as I live,” Pete said in 1981, “I may never make such a good recording.”

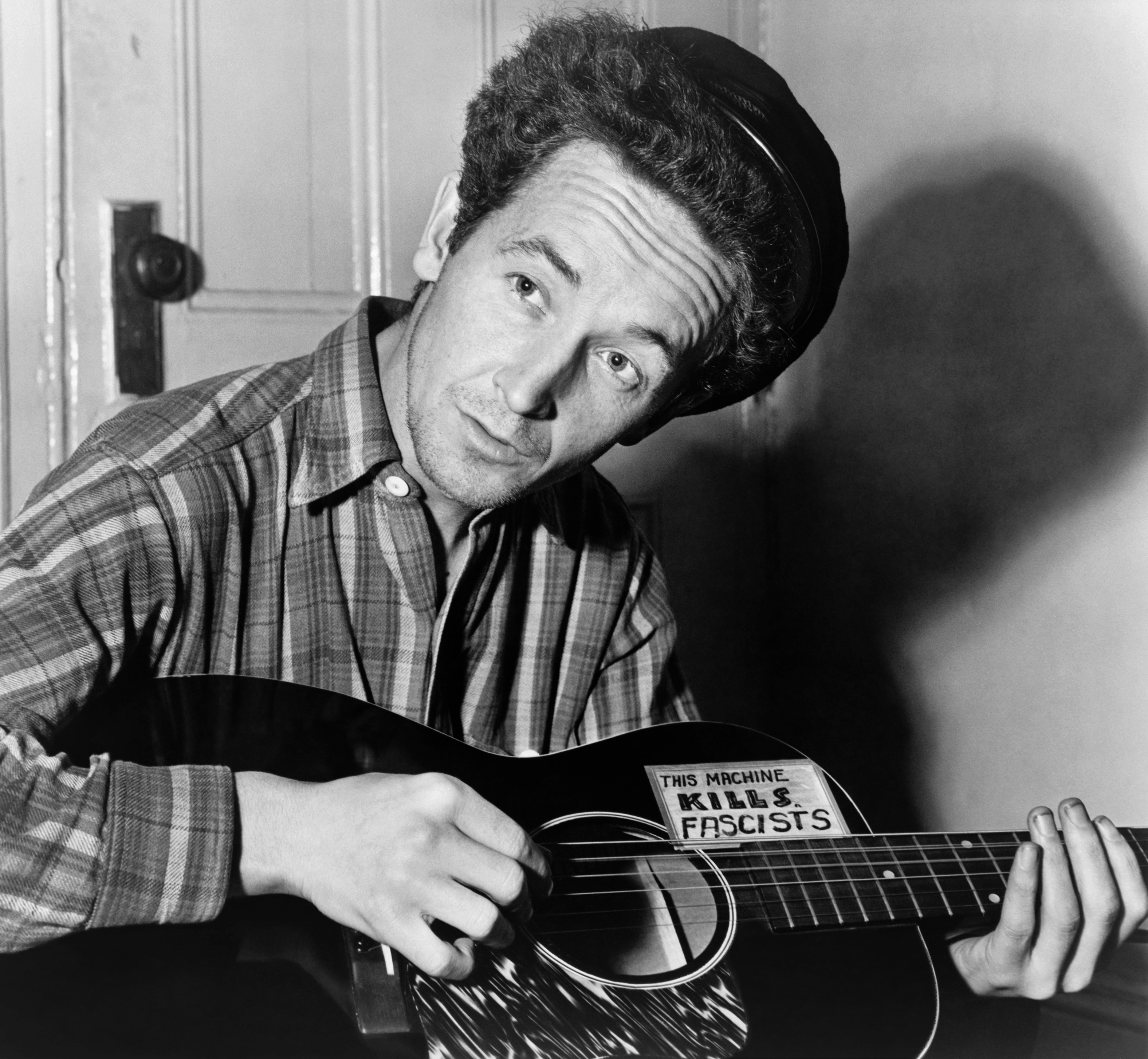

The FBI agent who interviewed Woody Guthrie about Seeger, on May 1, 1943 in New York, noticed “hanging on Guthrie’s wall, a large guitar on which there appeared the inscription, ‘This machine kills Fascists.’” Although the United States had by then been at war with fascism for a more than a year, the agent’s inference was ironic but all too typical: “It is this Agent’s opinion that this bears out the belief that the Almanac Players were active singing Communist songs and spreading propaganda.” The Lincoln vets, too, were branded as “premature anti-Fascists.”

Given his record, it was inevitable that Seeger, like so many others, would come under fire in the years of the Red Scare. In August 1955, he was subpoenaed to testify before the House Un-American Activities Committee. Unlike other witnesses, he declined to take the Fifth Amendment defense. But he refused to answer any questions about his political beliefs and associations nonetheless. “I am not going to answer any questions as to my associations, my philosophical or religious beliefs or my political beliefs, or how I voted in any election or any of these private affairs,” he said, according to the transcript included in the FBI file. “I think these are very improper questions for any American to be asked, especially under such compulsion as this.” But, he added, “I would be very glad to tell you my life if you want to hear of it.” A bit later in the hearing, Seeger underscored his patriotism:

Mr. Seeger. I feel that in my whole life I have never done anything of any conspiratorial nature and I resent very much and very deeply the implication of being called before this committee that in some way because my opinions may be different from yours, or yours, Mr. Willis; or yours, Mr. Scherer; that I am any less of an American than anybody else. I love my country very deeply, sir.

Chairman Walter. Why don’t you make a little contribution toward preserving its institutions?

Mr. Seeger. I feel that my whole life is a contribution, that is why I would like to tell you about it.

Chairman Walter. I don’t want to hear about it.

Seeger was cited for contempt, arraigned in 1957, and let out on a $1,000 bail. But by March 1960, the Court of Appeals annulled the sentence: HUAC had not made clear enough why it would have the authority to demand that Seeger answer its questions.

By then, however, Seeger had been blacklisted for almost a decade, resulting in a partial ban on radio coverage and a complete ban on national television. The ban would last for another seven years, until late 1967, when CBS’s Smothers Brothers decided to bring him back to the small screen for a performance. But the network censored the most political song on Pete’s set list that evening: his anti-Vietnam ballad “Waist Deep in the Big Muddy.” The protests were so ferocious that the Smothers Brothers brought Pete back in early 1968 for an encore of the song that did make it to the airwaves this time.

The file contains a couple of other curiosities worth mentioning. In the early 1940s, Seeger’s bohemian ways did not set well with his landladies. A Mrs. Mangioni, who rented him an apartment on Downing Street in Greenwich Village, New York, between May and July 1942, told the Feds that Guthrie moved in the very next day, and that Toshi visited often along with other friends. The group “was much too noisy most of the time,” she told the Feds: “She characterized them as a disreputable crowd, none of the members of which ever looked neat or clean-cut. Most of them wore lumber jackets and denim blue trousers and frequently appeared carrying guitars and other musical instruments.” Later in the file there are several letters to Hoover from citizens concerned with Communist infiltration, who see Seeger as a wolf in sheep’s clothing. One, who lived a couple of hours from Pete’s home in upstate New York, wrote to Hoover in March 1967 to complain that “a service organization in our small town is sponsoring a concert by a Mr. Pete Seeger,” about whom “it has been rumored that he is a communist.” “Mr. Seeger,” the writer added, “is apparently a negro in his late forties. I have no other identification.” (It was clear Seeger had not been on television for years.) Another concerned citizen set pen to paper in July 1970, after Pete had appeared on Sesame Street. “Can you please tell me if Pete Seeger is a member of the Communist Party and, if so, what involvement he has with it,” she wrote. “I have written to the show’s producer and the Info. Dept. advised me that they had not inquired into his political ideology and that whatever it is, it had no bearing on his performance on their show! But it does! If children think Sesame St. is good & they learn a Communist appeared on it then they say Communism is good!”

The FBI followed Seeger’s tracks closely as he began to achieve worldwide fame and spent increasing time abroad. In January 1967, shortly before the end of the blacklist period, he played in West Berlin and passed over to East Berlin for a couple of concerts. The reception was overwhelming. Victor Grossman, an American journalist who had fled the U.S. army to East Germany in 1952, had helped set up the gigs after introducing the GDR public to Seeger and other American folk through a radio series. [See Grossman article] “It was arranged for him to meet the great Ernst Busch (dearly loved in East Germany both for his singing and his magnificent acting in many Brecht plays, though with occasional run-ins or disputes with the idiots, as with Brecht),” he recalls. “This was a dramatic meeting, in a way, between two of the very greatest. Busch spent a long time in Spain during the civil war— not at the front directly, but putting together his great international Canciones collection, with about 150 songs in 15 languages. That helped make many of them known. And the songs he recorded in Barcelona, sometimes during the bombing, contained in that wonderful album of 1940 made some of them part of a legendary world leftwing folklore.” In May, Seeger wrote to Grossman to ask about the musical debates in the GDR, explaining that, in the United States, his early hit song “We Shall Overcome” was being adapted to the increasingly combative civil-rights movement:

I would be interested in hearing the various arguments which are going on today in the DDR, both pro and con American jazz, American folksong, and specifically the song “We Shall Overcome.” You probably know that many militant Negros now do not like to sing the song because they feel it is too passive and they don’t like forever saying that word “someday.” That word has been said for 2000 years to persuade working people not ot better their conditions now. And it is very interesting that when the song is sung, they always make a point of putting in the verses “Black and white together NOW,” and “We are not afraid today.” Furthermore after singing the song, quite often they will have a shouted cheer. One person will say “What do we want?” and the crowd shouts back “Freedom,” then “When do we want it?” Answer: “Now!” “Who do we want it for?” Answer: “All of us!” And these three questions will be asked over and over until the crowd answers them back at top volume.

In 1971 Seeger played in Cuba, accompanied by his daughter Mika and her husband, the Puerto Rican photographer Emilio Rodríguez Vázquez. The FBI was miffed: Seeger’s request for permission to travel to the island, filed in February 1968, earlier, had been denied by the State Department. From La Habana he flew straight to Madrid. Initially he had been hesitant to visit Franco’s Spain, but the Valencian folk singer Raimon, whom he had met in New York in 1970, had persuaded him that his presence would help the Spanish people break out of the narrow cultural mold of Francoism. A concert in Terrassa was a great success. A planned performance in Barcelona, however, was prohibited by the authorities, leading to student protest that made the pages of the New York Times. “In 1976, after Franco’s death, he came to sing to Madrid and Barcelona,” Raimon recalled in El País when Seeger died in January 2014. “In 1993 he came to the Palau Sant Jordi to be a part of the 30th anniversary celebration of [my first song] Al Vent, with his grandson Tao Rodríguez Seeger.”

Sebastiaan Faber teaches at Oberlin College.

I disagree, look at https://bookriot.com/2017/05/25/100-must-read-books-about-serial-killers/

[…] The Volunteer(Founded by the Veterans of the Abraham Lincoln Brigade), 2 Jan. 2016 . https://albavolunteer.org/2016/01/pete-and-the-feds-seegers-fbi-file-reveals-lincoln-connections/ Accessed 9 Oct. […]