The wars of Bill Aalto: Guerrilla soldier in Spain, 1937-39

Nothing is free, whatever you charge shall be paid

That these days of exotic splendour may stand out

In each lifetime like marble

Mileposts in an alluvial land.

—W.H. Auden

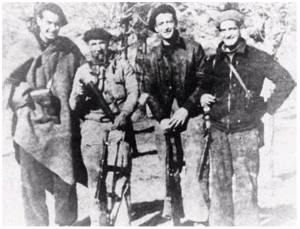

Just back from a mission behind Franco’s lines, probably late 1937. From left to right: Bill Aalto, a Spanish guerrilla fighter, Alex Kunstlich, and Irv Goff.

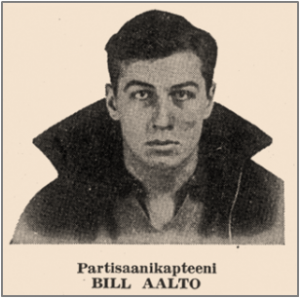

Bill Aalto was 21 when he left for Spain. His general profile seemed unremarkable among the American volunteers who would form the Abraham Lincoln Battalion of the International Brigades: a young communist, a child of European immigrants, impelled by the desire to make a mark on an impervious and unforgiving world, and pushed by the ravages of the economic crash. Like most of the volunteers, Bill vested his own hopes in the dream of the Spanish Republic. But for him the feeling was magnified by his particular family background, where the hopes, fears, and tensions between the old and new worlds stood out in sharp relief.

When Bill sailed from New York in February 1937 aboard the SS Paris, bound for Le Havre, France, he was making the reverse transatlantic journey his own mother had made 30 years earlier, at virtually the same age. Elsa Akkola, bright and well-educated, from a once affluent landowning family in southern Finland, had come to New York with high hopes. By the time she gave birth to Bill eight years later, a single mother in 1915, she had been worn down by the experience of domestic service, with its daily slights and sometimes more substantial humiliations. Bill’s early life was marked by her straitened circumstances and even more by her frustration and sense of isolation, learned in encounters with the hard-edged realities of social hierarchy in the city. Elsa gravitated to Finnish communist circles in New York, and remained staunch in those beliefs throughout her life with all the fervor that her Protestant upbringing had instilled in her.

Elsa was determined that Bill should stay on at school. Enabling this was likely part of the reason why in 1927 she married a fellow Finnish migrant, the more comfortably-off—and more conservative—Otto Aalto. They moved to what was, in the 1920s and 30s, the relative comfort of the Bronx, and Otto adopted 12-year-old Bill. But relations between stepfather and son worsened as Bill grew to be a bright and educated teenager. He stayed at school, but also went his own way—which was in some ways his mother’s too. He ran with the Harlem Proletarians, a Finnish youth club, and joined the Bronx Young Communist League. A politically literate streetwise boy, a voracious reader with writerly talent and a social conscience, he was already looking for a place in the world when the depression struck, followed rapidly by a personal and family tragedy—the death of Bill’s young half-brother, Henry. This family crisis catalyzed Elsa’s estrangement from Otto, deepened by their very different worldviews and politics. It also intensified Bill’s conflict with his stepfather—a conflict that would worsen over the years, eventually with irrevocable consequences. In 1935, when he was 18, Bill left home—and school—earning his living in casual jobs, before making the decision to go to Spain.

On his arrival, Bill was recruited immediately as a guerrilla soldier at the International Brigade (IB) collection point in Albacete—one of a tiny number of North Americans (and of only a relatively small number of International Brigaders overall) who fought in the Republican irregular forces, carrying out sabotage behind enemy lines. By late 1937 these irregular forces would be brought together—Spanish and IBers alike—as a single corps, the Fourteenth, of the Republican army. But when Bill arrived in the second half of February, everything was far more fragmented, as a result of the July 1936 military coup which had almost completely destroyed the coherence of the Republican armed forces.

This fragmentation meant that sabotage and demolition missions were planned and implemented autonomously in the early months of the war by individual military commanders, and were usually undertaken by Spanish soldiers. Simultaneously within the IBs, Soviet military advisers were also putting together guerrilla units. These advisers, who came mainly from army military intelligence (GRU), had arrived in October 1936 as part of the USSR’s response to Nazi and Fascist military support for the rebellion. They were keen to demonstrate the efficacy of irregular warfare methods to the hard-pressed Spanish Republican high command. In the early months, the GRU advisers also depended on supplies and men from local Republican army commanders, who frequently proved uncooperative. To resolve the shortage of manpower, Soviet advisers recruited International Brigaders. Among the nationalities recruited were several Finns (from Finland and North America, who were seen as hardy and resilient. Bill made the selection: he was big —approximately 6’ 2”—strong, fit and athletic. He also had a good knowledge of Spanish very well, having studied it previously, which set him apart from most other IBers

Joining the guerrilla unit was Bill’s own preference, an opportunity to fight the war more effectively, also with better odds for himself. Looking back from 1942, he described, with characteristic acuity, his dreaded image of war: “going over the top, getting ripped by bayonet and mowed down by machine gun and hanging on barbed wire. I became a guerrilla and stalked, saw no bayonets, met very little machine gun fire, cut the barbed wire.” Irregular warfare suited him—the close-knit group dependent on each other, the creative edge of danger that gave it meaning, but also the sense of a calculated risk and an opportunity to carry out more intricate forms of soldiering.

Recruited along with Bill was another tough, intelligent and charismatic American volunteer: the college-educated, New York Longshoremen’s union organiser Alex Kunstlich (aka Kunstlicht or sometimes Kunslich), who was seven years Bill’s senior. Shortly after finishing their training (at a demolitions school set up by GRU advisers near Jaén in southern Spain), Bill and Alex teamed up with another New-York volunteer-turned-guerrilla, the tough Brooklynite Irving Goff. From a family of Russian- Jewish origins, Goff had earned his living as a acrobat before becoming a Communist party organizer. Under Kunstlich’s command the other two served in a guerrilla group, one of many composed of International Brigaders and Spanish soldiers, operating mainly on the southern front, in the countryside of Cordoba and Granada. Bill did participate in some guerrilla operations in the northeast, on the Teruel front.

But he was not part of the Albarracín bridge-blowing operation in which Goff and Kunstlich were involved and which was fictionalized in Ernest Hemingway’s For Whom the Bell Tolls. Goff never actually met Hemingway and it is highly improbable that Bill did either. Their later responses to the possibility that they may have served as a model for Hemingway’s hero Robert Jordan illustrate their very different personalities. While the idea played to Goff’s ego, Bill had a nice line in ironic quips about Hemingway. (These appear, for example, in the always shrewd and often witty responses Bill gave to the famous U.S.- government-commissioned “Fear in Battle” study, which Yale sociologist John Dollard carried out in 1942. Dollard asked his testing subjects for responses to different soldierly scenarios and emotions. To the phrase “expects to be afraid in battle and tries to get ready for it,” Aalto retorted: “Hemingway should be kept out of this [study]”; to Dollard’s phrase “wonders ‘if he can take it’,” Aalto replied: “Give him For Whom the Bell Tolls.”)

By late 1937, as guerrilla operations on the southern front expanded, Kunstlich came to command much larger numbers in a unit in which Bill served as his operations officer and second-in-command. Bill was responsible for all the logistics, supply, and strategic planning of Kunstlich’s operations. He also drove the truck taking operations groups to their rendezvous points. Their work remained overwhelmingly that of demolitions—especially the destruction of transport and infrastructure (railways, roads and bridges). While some guerrillas were involved in partisan activities behind Francoist lines, these were a minority, and even then this activity was limited to temporary incursions. Such limits reflected the Republic’s military weakness, crippled by Non-Intervention, and the lack of arms to equip even its troops , let alone the peasantry in the Francoist southern rear guard.

Bill loved the intricacies of soldiering, perhaps for the pleasure of control it gave after the powerlessness of the depression and the irresolvable emotional tensions at home. In his quiet concentration on detail, he was much closer in temperament to Alex Kunstlich than to his other comrade, Goff. Bill was technically a very good soldier and was promoted rapidly—and ahead of Goff, his senior by 15 years.

In May 1938 Bill became a lieutenant but lost his comrade Kunstlich: Alex was captured and executed near Granada, after a spectacular lapse in his usual meticulous approach to operations—provoked in part by the calamitous effect of the great retreats of March 1938. As the Francoist armies surged down Aragón to the sea, they cut the Republican zone into two in early April. To try to restore Republican morale in the wake of this debacle, military authorities planned a daring action in which both Bill and Goff would participate. In what would be the only commando raid ever undertaken in Spanish military history, a Republican force of some 30 men freed 300 Republican prisoners-of-war held in a beach fortress on the southern coast of Spain, situated just behind the Francoist front line. The mission was a success, but it almost cost Bill and Goff their lives. They were cut off by Francoist troops and had to swim out to sea to reach Republican territory, skirting a hostile, sentry-encrusted coast. The Spaniards who were with them drowned. Bill and Goff survived largely because they were both champion swimmers. (In Bill’s case, this was courtesy of his time in the Harlem Proletarians.)

Bill was promoted to captain in June 1938. But 17 months of service had taken their toll. Well before the formal withdrawal of the Brigades was announced in September 1938, both Bill and Goff had become exhausted. Between July and November 1938, Bill spent three periods in the hospital with fever, colitis and what was by now chronic malaria. He wrote repeatedly to the Brigade authorities on behalf of himself and Goff arguing that they were no longer serving any useful purpose and would be better off returning to the United States to support Republican Spain on the publicity front. Bill also worried that his passport would cease to be valid if he remained abroad for more than two years continuously, a concern to him particularly because of financial responsibilities for his mother and young half-brother, John (Jusse), then aged 8. The wheels moved slowly—November before they were sent to a demobilization unit in Valencia; mid-January 1939 when they arrived by boat in Barcelona; early February before Bill sailed into New York. He had been gone exactly two years.

Crossing the lines

Bill came out of the war with the highest commendation of any awarded to the Lincoln brigaders, but he never told war stories afterwards. His sensibility was too attuned to the contradiction between the justice of a cause and the unspeakable violence that war demanded. (Demolitions work, too, involves causing mass death; nor was it always “clean” or certain to affect only military personnel.) In contrast, Goff loved to give the gory details of horrible experiences. When he did so, as other Lincolns later recalled, Bill would go quiet and walk away. Bill’s silence was evidence, too, of an interior change working upon him. As he later wrote, “the war is breaking us, but also remaking us.” He continued to be active with the Veterans of the Abraham Lincoln Brigade (VALB), speaking on behalf of the Spanish Republican cause and its refugees and prisoners. As paid jobs were hard to come by, he was moving around New York and Connecticut to earn his living from short-term jobs. One was as a general laborer on the U.S. army base at Ansonia. It’s unclear whether Bill’s work for the army had any bearing on the fateful decision of his stepfather Otto to denounce Bill to the FBI, which he did by visiting its New York field office in March 1941. He showed the agents the New York Times of January 20, 1939 which referred to Bill as a partisan leader and head of the returning Lincolns, and declared that his stepson constituted a danger to the United States because of his political views and because he’d been in Spain. Otto’s motives were doubtless a complex tangle of anger and revenge, directed also against Elsa, from whom he had recently separated. Otto’s political views were antithetical to Bill’s, but he may also have been perturbed about a perceived danger to his own status as a naturalized citizen. While the Lincolns were already under FBI scrutiny, it was Otto’s action that triggered the opening of a file on Bill. In light of his guerrilla corps service, the FBI recommended him for custodial detention. The detention was postponed when, a few months later, Bill volunteered for service in the U.S. army. The authorities decided that military service was an alternative mode of surveillance for Lincoln veterans. Like many other vets, once enlisted Bill found himself detailed to menial tasks. “I’m on the FBI shit-list,” he complained to a fellow Lincoln, “or else the Army’s own blacklist.” In his case it was both.

To escape what he saw as a waste of his talents, Aalto, like a handful of other Lincolns, seized an opportunity in early 1942 to be recruited to a newly created elite special force, the Office of Strategic Services (OSS). Its task was to parachute operatives into Europe to liaise with the resistance movements in the partisan war behind the lines. It was the only capacity in which the U.S. authorities were prepared to use the Lincolns’ experience and contacts from Spain. But despite Bill’s exceptional guerrilla expertise, he would never make it back into active service in Europe. In 1943 his world quite literally blew up, physically and psychologically, as the result of a second betrayal—this time by his comrades. The instigator was Irving Goff.

Not long after their return from Spain, Bill had told Irv in confidence of his sexual preference for men. Goff now stirred up fear and unease among the small group of Lincoln veterans in the OSS that Bill’s sexual difference would mean a permanent security risk for them all. The implication was that Bill’s difference made him a weak link, an easy prey for turning—not by enemy agents, but by the U.S. political establishment. In other words, the Lincolns’ reaction to Goff’s broadside against Bill was strongly influenced by the climate of suspicion against them in the OSS. Still, a current of subconscious machismo and social prejudice was likely part of the picture too. Goff’s own motives were probably more complicated. An intensely competitive individual and rather self-important, he was irked by Bill’s rising military star and promotion ahead of him, first during the civil war and afterwards in the OSS. But there is no doubt that what finally sealed Bill’s fate in the OSS was the nature of the political times and the sense of vulnerability it inspired in the other Lincolns.

Although the OSS commander would have preferred to keep Bill on board, he acquiesced to the veterans’ collective request, transferring him out of his active service to a military training camp in Maryland. There Bill’s job was to train new officer recruits who outranked him but who lacked combat experience and military expertise. He instructed them in sabotage and demolition techniques. In the course of a training session, in September 1943, an officer-recruit dropped an unpinned live grenade. Bill seized it, but before he could throw it, it exploded, blowing off his right hand and part of his forearm. He was invalided out of the service with a disability pension.

The accident led Bill to confront full-square the things that made him different. He couldn’t belong any more in an unselfconscious way to the world of his comrades, to the “good fight,” as they would always call the battle in Spain. In the accident’s aftermath Bill’s remaking of himself, a process already underway, further accelerated. He did not renege on his political beliefs or reject his comrades—to the contrary, he remained fiercely loyal, despite the OSS incident, and at increasing cost to himself. Instead of rejecting his past, he simply walked away. He left behind the war hero persona, the political soldier, the discipline of the Communist party, and went in search of something else.

In the remaining decade-and-a-half of his short life, he would cross worlds on a singular journey of the spirit and mind. The questions he came to ask had their roots in the seismic effects of war. Many of these questions would later become increasingly mainstream from the 1960s on—even though Bill would not live to see these social changes. Of the many scattered literary epitaphs to Bill Aalto, the most resonant can be found in the work of W.H. Auden, who became a friend in early 1940s New York and remained a kind and loyal one thereafter, continuing to help Bill in many practical ways, even when the pressure of external events made him quite unbearable to be around. It was Auden’s retreat on Forio d’Ischia (Italy), where Bill lived for a time in 1948 and 1949, which is recalled in the lines quoted in this article’s epigraph. But through the haze of a tranquil summer day on a Mediterranean island, they evoke something else too—the life-breaking history of the mid-20th century.

Helen Graham teaches European History at Royal Holloway, University of London. The research for this article has involved work over many years on multiple continents. Aalto’s is one of five lives featured in Graham’s forthcoming book After the Wars in Spain: Lives Salvaged from the Dark Twentieth Century, to be published next year.

GREAT ARTICLE, HELEN. WE MEET AT THE ALBA FUCNTION SEVERAL YEARS AGO. I WAS A FRIEND OF SLYVIA THOMPSON-MAY SHE REST IN PEACE-LOOK FORWAR TO YOUR BOOK AND HOPE YOU ARE WELL.

I wonder where I can request the book when it is available. My dad knew Bill Aalto in NY and would be very interested in getting the book and reading more about his amazing life. Thanks so much for this informative and well written article.

Jo

Muy buen artículo. Sadly people like Bill Aalto is poorly remembered (or not remembered at all) in Spain, and we own them, at the very least, our gratitude. Thanks for the article -informative and so well written that is a joy to read- and for giving us a window to see Aalto´s life.

I suppose the book has not yet been published, but maybe this year.

A small misspelling in the story: Jussi (not Jusse) is the Finnish variant of John.

Bill Aalto was HOMOSEXUAL, and that was very important in all aspects of his life, including the political activism.