The man who can’t say no: Preston is working harder than ever

Paul Preston is impossible to avoid. Author of twelve books, editor of several more, and director of an important series on the subject, he towers mile-high in the landscape of Spanish Civil War scholarship. And yet in person he can be quite elusive. A previously arranged meeting for an interview in London first had to be postponed, then canceled. A subsequent attempt at a phone interview caught him in the midst of a frantic attempt to correct the Spanish and Catalan proofs for his forthcoming biography of Santiago Carrillo, the recently deceased Communist leader. Another week later, the stars aligned, and we talked for hours. Preston, it turns out, does not purposely avoid engagements. The problem is quite the opposite: he is extraordinarily generous with his time and, if anything, too quick to commit. The Carrillo proofs are off his table, but the pile of work is still stacked to the ceiling of his cramped London study. “I’m up to my eyes with things I promised to do in terms of reviews and chapters for people’s books, and so on,” he laughs. “It’s the problem of being a girl who just can’t say no.”

Preston has officially retired from his post at the London School of Economics and has, in recent years, been in less than perfect health. But he is continuing as head of the Cañada Blanch Center and shows no signs of slowing down his breakneck pace. What keeps him going? Is there anything left to prove, or is his ambition really boundless? Preston self-analyzes reluctantly. “I don’t think it’s ambition at all. I just don’t know what else to do. There are still lots of things I want to say about twentieth-century Spain. If I could live another fifty years, which obviously is not going to happen, I don’t think I would run out of things to say—though I would likely run out of places ready to publish it. But professional ambition? At this point those things don’t matter anymore. I got a full professorship when I was 38, was appointed dean shortly afterwards and had a chance to have a career as a highly paid university administrator. But I just wasn’t interested. All I’ve ever wanted to do is teach and write.”

Paul Preston was born in 1946 in postwar Liverpool. When he was an infant, he and his mother both contracted tuberculosis. Paul eventually got better, but his mother never did. She died when Paul was nine, after spending the last seven years of her life confined to a sanatorium; Paul was mostly raised by his grandparents. He had to take the ferry to get to his school, St. Edward’s College, which was run by the Christian brothers armed with “straps” made from whale ribs covered in black leather. His life changed when he got a scholarship for Oxford to study history.

“For someone with my background getting into Oxford was nothing short of miraculous. Still, I can’t say I learned much as an undergraduate. The history curriculum was unspeakably boring. And the teaching, insofar as there was any, was utterly abysmal. It was really incomparable to how we think of teaching undergraduates now. You were thrown into a very deep pool—and they didn’t even stay around to see if you could swim. What made it worthwhile were the amazing libraries and the lectures by great thinkers like Isaiah Berlin.”

A second turning point came in the late 1960s. “I was lucky to get offered a scholarship to the University of Reading, where it was possible to construct an MA entirely on the 1930s. One of the courses I took there was a class on the Spanish Civil War with Hugh Thomas—a very complicated but fascinating man. Still, even then my interest was almost entirely intellectual. I had no background to speak of, none of the language, nothing. But once I got hooked and had read everything I could in English, I decided I had better learn Spanish. This I did by reading with a dictionary and hanging around with Colombians in the student bar. Then I went to Spain. It was the beginning of a life-long love affair. In the late 1960s and early 1970, I was living in the 1930s, entirely absorbed in my research on the origins of the CiviI War. It was on my return to England that I got involved with the anti-Franco opposition, acting as an interpreter for the Junta Democrática, and I came to know the top brass of the Socialist and Communist Parties and some anarchists as well.”

Preston never stopped being a working-class kid from Liverpool. He curses like a sailor; and he stubbornly roots for Everton Football Club, of which he speaks in the first person plural (“I wouldn’t mind Messi playing for us”). When I naively admit to a certain admiration for Luis Suárez, the Uruguayan-born striker of Everton’s arch rival FC Liverpool, the phone nearly explodes in passionate indignation: “Luis Suárez is a loathsome, cheating bastard. He is a great footballer, don’t get me wrong. But he dives, he cheats, he bites, he kicks people behind the referee’s back—everything about him is vile.”

A similar kind of passionate investment drives Preston’s work on Spain and his sympathy for the Second Republic. “I came from a fairly left-wing family. You could not really be from working-class Liverpool and not be left-wing. Emotionally, in my feeling for the Republic I think there is an element of indignation about the Republic’s defeat, solidarity with the losing side. Maybe that’s why I support Everton, although Everton wasn’t the losing side in my day.”

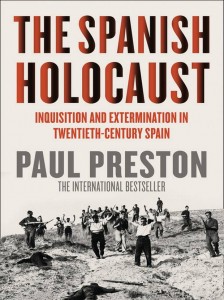

His forty-year long engagement with Spain has led him to a clear set of positions that he defends tooth and nail, with the fruits of decades’ worth of research to back them up. Against competing accounts from conservative scholars such as Stanley Payne, for example, Preston argues that the blame for the outbreak of the war cannot be shoved in the shoes of the radicalized Spanish left. He also believes that the war policy followed by the Spanish Communist Party—a centralized army; prioritizing winning the war over making revolution; and continuing the fight in spite of the increasingly slim prospects for a Republican victory—was the most sensible one available. And Preston convincingly argues—most recently in his Spanish Holocaust (2012)—that, while violence and atrocities were committed on both sides, Francoist repression of the enemy was not only far more extensive but also consciously planned, imposed from above, and based on a colonial, semi-racist view of the Spanish workers and peasant. “To me there is a huge moral difference between the two. Of course, there are killers on both sides who display the same kind of psychopathology. But generally speaking there are crucial distinctions. How come there is so little rape on the Republican side, while it is a deliberate instrument of policy on the Francoist side?”

His forty-year long engagement with Spain has led him to a clear set of positions that he defends tooth and nail, with the fruits of decades’ worth of research to back them up. Against competing accounts from conservative scholars such as Stanley Payne, for example, Preston argues that the blame for the outbreak of the war cannot be shoved in the shoes of the radicalized Spanish left. He also believes that the war policy followed by the Spanish Communist Party—a centralized army; prioritizing winning the war over making revolution; and continuing the fight in spite of the increasingly slim prospects for a Republican victory—was the most sensible one available. And Preston convincingly argues—most recently in his Spanish Holocaust (2012)—that, while violence and atrocities were committed on both sides, Francoist repression of the enemy was not only far more extensive but also consciously planned, imposed from above, and based on a colonial, semi-racist view of the Spanish workers and peasant. “To me there is a huge moral difference between the two. Of course, there are killers on both sides who display the same kind of psychopathology. But generally speaking there are crucial distinctions. How come there is so little rape on the Republican side, while it is a deliberate instrument of policy on the Francoist side?”

And yet he is still capable of surprising himself and his readers. Take Santiago Carrillo, who fought as a young man in the Civil War and went on to lead the Spanish Communist Party for 22 years—through postwar exile, the demise of Stalinism, the Spanish transition, and into Euro-Communism. Preston’s new biography, which just came out in Spain as El zorro rojo (The Red Fox), does not paint a pretty picture. Carrillo, who died last year at the age of 97, managed over time to build up an image as a wise senior man of state—a myth that Preston shatters without mercy. “Carrillo,” he sums up the thrust of his book, “was one seriously nasty piece of work. The ruthlessness with which he rose to power, destroying comrades along the way, is just mind-boggling.”

Will your book shock the Spanish left?

“The stuff I found in the archives will be shocking for those who think of Carrillo as the Mother Theresa of the Transition, but not for many others. There will be people on the right who say: Even left-wing historian Paul Preston criticizes Carrillo. I knew him and liked him but I ended up indignantly concluding that he undermined the struggle against Franco. By imposing unrealistic strategies, and destroying those who criticized him, he squandered the efforts and sacrifices of the hundreds of thousands of people who suffered under and against the dictatorship.”

Have your views of Spain and its history changed over the past 40 years?

“Yes, I think they have. My anti-Francoism hasn’t diminished much, and my deep conviction that the Republic was right is still in place. But over time I have become readier to see good and bad on both sides. That’s obvious even if you look at earlier books like Comrades or Doves of War, where I write sympathetically about two right-wing women, Mercedes Sanz-Bachiller and Pilar Primo de Rivera. Carrillo is also a case in point. When I did the research for The Spanish Holocaust, which is a book I had been writing for years, I was quite shocked by the scale and senselessness of anarchist violence—which doesn’t mean I am not able to see that a lot of this violence stemmed from social deprivation. Still, when I first started to read about Spain in the 1960s, I kind of thought that the anarchists and the POUM were romantic heroes. I certainly don’t think that about them now.

“You see, my vocation—if that is the word—is as a biographer. I am happiest when I write about people. Even in books that are not ostensibly biographical, like The Spanish Holocaust or The Coming of the Spanish Civil War, I always try to put people at the center. Although I believe in the social and economic dynamics of history, I also very firmly believe in the role of individuals.”

You publish in Britain and the United States, but also have a massive readership in Spain. For whom do you write?

“That’s a difficult question. I write in English, and at the end of the day I am always happier with the English version; it’s more mine. But in a bizarre way, I write for the same audience in English and Spanish. I have always thought that the success of my books in Spain has to do with the fact that I essentially write for an English-speaking audience. That means I have to explain things as I go, and make it interesting. In an English or American university, after all, no one is obliged to study Spanish history. Therefore courses and books have to be attractive. And that means they have to be comprehensible, accessible, readable. Spanish readers rather like that, too. Because in general Spanish academics just write for other academics—though this has changed a lot in the last twenty years, in part thanks to people who have trained with me. When I promote my books in Spain, particularly at the big book fairs, I get to talk a lot to ordinary readers, whose stories are often amazing. And that makes it all worthwhile.”

I’ve long been fascinated with a strange phenomenon: Many people around the world are so strongly wedded to their existing views of the Spanish Civil War that they seem immune to reasonable argument based on historical research. Myths about the war are incredibly tenacious. In a recent public email discussion with some particularly stubborn individual, you wrote, with some desperation: “I wish I knew what it is about the Spanish Civil War that makes people think that they can say whatever they like without much in the way of knowledge. Ángel Viñas and I have spent ninety years between us studying the war, and we are still reluctant to say things without solid proof.” Don’t you get tired of that?

“I do. The utterly prejudiced idiocy that is produced by some people is frustrating, that’s absolutely right. You write reasonable stuff based on years of research, and they just dismiss it out of hand, refusing to produce any evidence for their assertions. Friends of mine who work on, say, Nazi Germany, such as Ian Kershaw or Richard Evans, don’t have to deal with that. It’s accepted that being critical of the Nazis is a reasonable place to start. That is obviously not the case with a critical stance on the Spanish Right during the Civil War or the Franco dictatorship thereafter. It’s a real problem. You’ve almost got to argue from first principles every time.”

Does working on the Spanish Civil War require a particular kind of temperament? People like Michael Seidman, Stanley Payne, or Ángel Viñas seem to relish the scholarly street fight.

“Academe is a vicious world, that’s certainly the case. Still, I challenge you to find anywhere in any of my writings in which I have ever attacked another historian ad hominem.”

You also have had your share of enemies in Spain, starting with pro-Franco “historians” like Ricardo de la Cierva.

“There is a book by De La Cierva called No nos robarán la historia (They Won’t Steal Our History) of which nearly half is an attack on me. It starts off something like this: Once upon a time, five young men were born in Liverpool. Four of them, who later became known as the Beatles, devoted their lives to song. The fifth, known as Paul Preston, devoted himself to telling lies about Spain.

The enmity must have to do with the fact that you command your share of media attention. Stanley Payne, too, is very present, especially in the right-wing media, where he freely expresses opinions about Spain’s current political situation. How do you deal with the fact that the Spanish media pay so much attention to what foreign experts like Payne or yourself say?

“I could be in the Spanish media all the time if I were willing to let fly with extreme opinions. But whenever I speak to the Spanish press, I speak with an intense awareness of personal responsibility. For instance, I am amazingly careful with my opinions about the monarchy. I know that people listen to what I say, so I try to say as little as possible. I am not a monarchist, but I do feel that Spain is in a particularly difficult position. And the last thing it needs is institutional instability.”

Given Spain´s current state—the severe economic and political crisis, the endless corruption scandals—it must be hard to read the papers.

“Yes, it is. But my love affair is not with the Spanish political class. There is not much to admire in the British political class, either, or for that matter in the political class of any country I can think of. Still, it is sad and infuriating. It gets to me because I love Spain and I hate to see people suffer. And I get obviously very indignant about the scale of the corruption. It puzzles me at a deeper level, too, though, and I would like to be able to explain it better. One of the projects that I am supposed to be doing, in fact, is an overall history of twentieth-century Spain. Now in one sense I could do that with my eyes closed, standing on one leg: I’ve covered all the ground, and I could just cobble together a resume of all my books. But I would actually like to do something more original. I want to pose larger questions: Why the violence, why the corruption? But those are incredibly difficult questions to answer. How did the Transition, which was such a good thing, end up in this mire? I can throw out hypotheses, but I am not entirely sure. You can come up with theories about traditions whereby public service is being used for private benefit, and so on. But how did it ever get to the scale that it did? Is it specific measures, like changing the law to give local authorities the power to re-zone land? Or is it something much more profound, more to do with cultural history? Could the attitudes in Spain have been the same during the Republic, with the only difference that the opportunities weren’t there? I don’t know.”

You recently published a revised edition of your biography of King Juan Carlos. He is not doing particularly well. What is your assessment of his influence since the 1970s?

“Overall I think the King played a fantastic role during the Transition. In the last years of Francoism he helped ensure that bloodshed would be kept to a minimum. Had he done what Franco intended him to do—which was to maintain the dictatorship—I think violence would have been much more widespread. He played his role very well, and with immense courage. But it was a pragmatic decision: I don’t think he was particularly a committed democrat. When he became a ceremonial head of state, after 1982, he continued to play a positive role. He became a very good trade ambassador for the country, for instance. And at a time when Spain was—and still is—deeply divided, he provided a genuinely neutral headship of state. Yet, with time, temptations have got the better of him.

“I can tell you that in personal terms he can be very funny and great to spend time with. I don’t know many monarchs, but I’ve met the Queen of England a couple of times and she could freeze your soul with a glance. Juan Carlos is warm and affable. Not that that ultimately matters much: Santiago Carrillo was always affable and funny, and we have all heard about how charming Hitler and Himmler could be.”

Will the monarchy survive its current crisis?

“I have enough trouble trying to interpret the past to try to interpret the future. But I certainly think that the circumstances that would bring about major institutional change in Spain—such as the end of the monarchy—would mean massive chaos, with involvement from the army, and so on. It could be very nasty.”

So you are saying that Spain is not ready for a republic?

“Well, it’s difficult, isn’t it? This is the problem with counterfactual speculation: you don´t know the circumstances in which things will happen. If, for the sake of argument, Juan Carlos were to abdicate and Felipe decided to hold a referendum on the constitutional future of the country, the republicans will probably win. And then it might be possible for a republic to come in peacefully. But that is a huge assumption.

“In the end it’s simple. If the economic situation improves, all the problems of the monarchy will go away. If the economic problems don’t improve, then there could be pressure against the monarchy that is really just a reflection of economic and social discontent. And that could lead to real instability.

“But I repeat, I’m no good at predicting the future. Look at the transition. Although it went more or less exactly as Claudín and Semprún had said it would, I personally never expected any of that to happen. And I was there, I was involved!”

Sebastiaan Faber is chair of ALBA’s board of governors and teaches at Oberlin College.

Wonderful interview. Loved it!

Paul Preston is my favorite historian of the Spanish Civil War. His works have profoundly influenced my opinions of the conflict I have studied for over 60 years. Thanks Paul.

Good interview.

he leido muchos de sus libros y me refiero al de los corresponsales y en particular Steer. Guernica me intriga mucho y yo pienso que usted sabe algo que no cuenta y tengo mucha curiosidad. Porque usted lo,insinua, he descubierto como se bombardeaba en Iraq a “savages and barbarians” con toda impunidad, pero no Guernica, en Europa. Esto ha satisfecho mi curiosidad. Es lo mismo pero es la policia aerea en pobres campesinos. Durante años. Peor que Guernica.

Lo otro, que no se, pero sospecho, es la creacion del mito Guernica. Iraq no tiene periodista ni artista, no tiene un Picasso escandalizado por el tratamiento a los beduinos. Steer se las arregla para conseguir el maximo de publicidad y usted cuenta que cuando muere, joven aun, lleva puesto el reloj que le regalo J.A. De Aguirre, reloj de oro. Yo sospecho que hubo mucho intercambio de dinero en propaganda y que usted lo sabe y no lo cuenta. Y me gustaria saberlo. Hay varias personas de las que sospecho. Mr Preston, por favor, cuente lo que sabe.