In the footsteps of the Lincoln-Washington Battalion

The Lincoln-Washington Battalion was in Aguaviva at the end of December 1937 before being sent to the battle of Teruel. Photo Anna Martí.

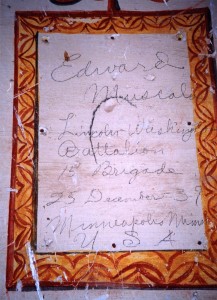

(Versión en castellano aquí.) At the end of 2004 a good friend of mine found, by chance, a piece of graffiti on a wall in the chapel of San Gregorio in the town of Aguaviva (Teruel). It had been written on Christmas Day 1937 by Edward Muscala, an American member of the International Brigades. Although Aguaviva is the hometown of my father, my family was unaware of the presence of American brigaders there. My curiosity led me to investigate who he was. After much research and help from ALBA I discovered that Edward was 26 years old when he arrived in Spain in August 1937 from Minneapolis. A member of the Young Communist League (YCL), he left behind a wife and son of a few months. But what struck me most was to learn that he died three months later in March 1938 during the Retreats of the Aragon front, after leaving his name written on the chapel wall.

In early 2009 a group of interested individuals began to investigate the presence of the Fifteenth Brigade in the area of Batea and Corbera d’Ebre during the Great Retreats. This group consists of two local Catalan historians, Vicenç Julià and Miquel Sunyer; Alan Warren, an English historian of the International Brigades based in Catalonia; my husband, Enric Comas; and myself. As a basis for our study we used the brigaders’ accounts, photos from the Tamiment Collection, interviews with the people of the area and field work for the locations. We do not think that our research is finished yet as we continue to receive information from the locals. This is just the beginning.

The camp in Batea (March 18-26)

![11_0265s_Major Robert MerrimanEstado Mayor [Headquarters]Batea_mar 38 copia](https://albavolunteer.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/07/11_0265s_Major-Robert-MerrimanEstado-Mayor-HeadquartersBatea_mar-38-copia-300x221.jpg)

Fifteenth Brigade Estado Mayor, Batea, March 1938. (Tamiment Library, NYU, 15th IB Photo Collection, Photo #11_0265)

Thanks to the photos taken by Harry Randall and his photographic unit, we eventually found the farm building that housed the General Staff of the Fifteenth Brigade—its Headquarters—near the town of Batea. Once we had located this site we were able to identify another nine photos taken in the vicinity and also the location of the Brigade’s camp. The Brigade was there from March 18, after participating in the defense of Caspe, until the 26th, a period that they spent in reorganization. On the 18th, 125 American brigaders arrived from the training camp of Tarazona de la Mancha. Among them was Alvah Bessie, whose diaries and book, Men in Battle, have been very useful for identifying locations and chronological dating.

Even after so many years we were able to locate over 400 “chabolas” used as shelters for the brigaders, located logically in an area close to the HQ and the Batea-Maella road. These small shelters were dug at the foot of mountain overhangs. To their front a simple stone wall was built for protection and then camouflaged with pine branches. Sometimes it was a simple semi-circle of stones. Usually the soldiers had to crawl inside on all fours; each shelter could accommodate several people. The camp was located strategically to the rear of the fortified line along the river Algars. This line of bunkers was originally built in 1936 at the start of the Civil War, with the aim of defending the entire border of Catalonia, but it was never completed or provided with the artillery pieces necessary for that purpose.

Machine gunners building nests; Batea, March 1938. (Tamiment Library, NYU, 15th IB Photo Collection, Photo #11_0292.)

The site of the machine gunners nest at Batea today; part of the trench is still visible. Photo Anna Martí.

Alvah Bessie wrote that when the new volunteers arrived at Batea they found the veterans very demoralized and with a shortage of weapons. One should remember that since March 9th, when Franco began the great offensive, the Lincoln-Washington battalion had suffered heavy casualties. For a week it had been forced to flee because of the great Fascist push. The Brigade did all that it could to try to raise morale. We have photos depicting activities such as a class of topography, soldiers digging trenches and two fiestas. In the evening of March 23th, ten volunteers received a wrist-watch as a reward for their personal courage, and on the 25th, four women from the JSU (United Socialist Youth) and a young Spanish soldier came from Barcelona to give them inspiring speeches. That day they also had a fiesta with cheap champagne, food, bonfires and songs. The veterans suspected that something was about to happen, and it did, the very next day. On the afternoon of March 26, they marched to a new camp, away from the front, just north of Corbera d’Ebre. Their march coincided with the resumption of Franco’s offensive in Caspe to try to cross the river Guadalope.

The Camp at Corbera d’Ebre (March 27-30)

Washing up. March 1938. A villager recalls that a group of villagers were paid to go to the house of the well to shave the brigaders who, he said, had beards of several days. In the photograph they are washing and it probably was taken that day. (Tamiment Library, NYU, 15th IB Photo Collection, Photo #11_0320.)

Thanks to Vicenç Julià, who was able to link photos from the Randall collection to particular locations, we now know that the brigaders were camped in the valley of Canelles, a valley with vineyards and olive trees near the village. Although she was only eight years old at the time, a woman from the town vividly remembers the tall brigaders walking down the streets of Corbera d’Ebre, speaking a language she did not understand; she did not recall that they ran into any trouble. What struck her most was to see an African American for the first time.

On March 29, Fascist troops succeeded in crossing the river Guadalope. In front of them lay two more rivers: the Matarraña and the Algars. The next day they managed to cross the first. The Fifteenth Brigade was sent to defend the second river, the Algars. That day, March 30, early in the morning, the volunteers of the Fifteenth Brigade were given new rifles, still covered with grease, and in the afternoon they left the camp at Corbera d’Ebre to their new positions in the frontline.

Going to the Botaja Front, March 1938. The moment of the march from the camp to the front. These pictures were mistakenly labeled as "Going to the Botaja front" There is a misspelling and it should read "Going to the Botja front" because Botja is a ridge where the Fifteenth Brigade Estado Mayor as well as the Canadian and Spanish battalions were eventually situated. The 2 pictures were taken from the same point but focused in opposite directions. (Tamiment Library, NYU, 15th IB Photo Collection, Photo #11_0327.)

The Algars Front (March 31-April 1)

Going to the Botaja Front, March 1938. (Tamiment Library, NYU, 15th IB Photo Collection, Photo #11_0328.)

The four battalions of the Fifteenth Brigade were moved toward the front line, with the British battalion in a more advanced position marching westwards beyond the village of Calaceite. They made the first contact with the enemy—unexpectedly—when in the morning of March 31, as they were leaving the town, they met some Italian tanks from the CTV. The skirmish caused 150 deaths; another 140 men were captured.

The Lincoln-Washington Battalion was sent to cover a gap between two battalions of the Eleventh Brigade (the Thaelmann and the Edgar André), northwest of Batea in the area of the hills of Cuadret and Vallbona. We think that we have been able to locate the positions of the Lincolns: Alvah Bessie’s Men in War describes the Brigade first-aid post as “a great lime-washed stone house” and a neighbor from Batea remembers seeing first-aid men in the house of Venta de Sant Joan during the fighting. The positions in these hills were defending the access of the old road linking the towns of Fabara and Vilalba dels Arcs. We have found stone parapets, taking advantage of the rocky terrain, and material such as bullets, clips, some pieces of hand-grenades and tin cans. In the position held by the German Edgar André Battalion we have found a great deal of cans and even some unexploded grenades.

The Lincolns did not hold these positions for long. They saw little action, with the exception of the night of March 31 to April 1, when some units of the Nationalist 55th Division attempted to penetrate the area. During the first hours of that April 1, the battalion remained calm without taking part in any action, ignoring the powerful forward attack by the Rebels that had severely punished the Canadian and Spanish battalions located on the Gandesa-Alcañiz road. Eventually they were forced to leave their positions and retreat towards Gandesa. Once the Chief of Staff Robert Merriman had ordered the withdrawal, he went to find his countrymen. In front of the house of Venta de Sant Joan units were mustered; once the route had been decided, in the direction of Vilalba dels Arcs and Gandesa, they marched, as Alvah Bessie recounts, at about 7:30 in the evening. However, the brigaders were unaware that, that very day, the Navarrese 1st Division had rapidly advanced toward Gandesa, occupying the villages of Pobla de Massaluca and Vilalba dels Arcs. The Nationalist had effectively surrounded the Lincoln Washington Battalion, cutting off their retreat.

Withdrawal (April 1-2)

Because we know the exact location from where they began the withdrawal and the direction they took, we have been able to developed the route the Batallion likely took. We know that they marched from the first aid post down to the Nonaspe-Batea road, where the brigaders rejected the ammunition offered because they wanted to travel light. They marched along the road until they reached the point where the previous day they “had entered the lines,” as Bessie writes. Since this is the location of the old road to Vilalba dels Arcs, this may have been their route. The fact that Alvah Bessie’s group, which got separated from the battalion, ended up in the middle of a Nationalist Requeté camp in Vilalba dels Arcs helps confirms this assumption. At dawn on April 2nd, the rest of the battalion reached some hills overlooking Gandesa. They had walked about 20 kilometers along unknown paths on a dark moonless night, carrying their equipment, tired, hungry and hoping to get safely to the town, which was believed to still be in Republican hands. Konrad Schmidt, a Swiss brigader, who during the retreat ended up mixed with the Lincolns, described the point from which they overlooked the village as a high plateau; we believe that this area could be Els Tossals, where there are two hills together.

There are many different versions of what happened on April 2. Knowing the area, we are inclined to regard as plausible the versions that describe an attack on Gandesa, with the Lincolns in turn being attacked by Nationalist artillery and cavalry. On one thing the brigaders’ memoirs agree: it was a sweltering day–a fact that the meteorological record confirms.

According to the brigaders’ accounts, when night fell and the scouts returned with the news of having found a possible escape route, the men left their positions and marched in single file into enemy territory. (Corbera d’Ebre had been occupied at noon on the April 2.) From the area of Els Tossals there leaves a trail, hidden from view from Gandesa, which descends to the Vilalba dels Arcs road and then winds up, also protected, to the hills between Gandesa and Corbera d’Ebre. There, on the ridge of those hills, there is a cattle route marked on the maps they carried. There are several reasons why we think they may have followed this route. For one, it is an easy path to follow because it is wide, much used and protected by a pine forest; further, the trail crosses the Gandesa-Corbera d’Ebre road at a place between the two municipalities; it runs parallel to the Vall de Canelles—familiar territory where the brigaders were camped some days before. Once the path crosses the road, it leads to the village of Miravet, where there was a ferry to cross the Ebro river. It seemed a good plan of escape. However, the Lincolns were unaware that when reaching the main road the good path turned into a narrow corridor with high banks preventing any escape if they were intercepted by some enemy patrol. This may precisely been what happened: the battalion was reportedly broken in two; the first group—which included the Chief of Staff, Major Merriman, and Political Commissar Dave Doran—was intercepted, and the two men possibly captured.

This scenario does not match the version of events presented by the Valencian soldier Fausto Villar in his unpublished memoirs, written many years after the fact—which may explain the many inconsistencies in his account. He recalls that he witnessed Merriman’s falling, for instance, but that may have occurred during the attack on Gandesa earlier that day. Villar describes the indicident as happening in the morning, after which he fled from the scene. Who says that Merriman could not have escaped from that situation and returned safely to the battalion? At the moment we have no other evidence apart from our knowledge of the area and an anonymous witness who assured that Merriman was captured and later shot in Corbera d’Ebre.

What we do know is that the night of April 2, the Lincoln-Washington Battalion ceased to exist as such, breaking up into small groups that desperately fled to the river Ebro.

The rout to the Ebro

The retreat became a rout. To reconstruct events, the recollections of the people living in the area at the time are an invaluable resource. Vicenç Julià, a historian from Corbera d’Ebre, has spent several years collecting oral histories from his neighbors about the presence of brigaders in the area. He always asked the same question: “Have you ever seen brigaders, alive or dead, during the rout of the Aragon Front in April?” Thirty-seven people agreed to be interviewed; it is through their stories that we have obtained the accounts of the interaction between locals and brigaders. We were even able to make a map with the locations where they were seen alive, shot, killed or buried. The reason for this contact between the brigaders and the locals is that upon receiving the news that Franco’s troops were heading towards the village, people, as usual, fled to their massos (farm houses), which were located in the outskirts, where they encountered the fleeing volunteers. The recollections of brigaders and locals agree in many respects. The locals recall that the brigaders moved in small groups, approaching them with caution and asking for food, drink, and directions. All asked for the same: THE EBRO. A villager received a watch from a brigader, another a compass. The locals also told us of a group carrying a Republican banner. One brigader who stayed behind to provide cover for his comrades was eventually killed by grenades hurled by Moroccan soldiers.

Initially all captured volunteers were shot, but after a few days they were taken prisoner. The 87 captured Lincolns were taken firstly to Alcañiz, then to Zaragoza where they ended up in the prison of San Pedro de Cardeña in Burgos, where they suffered great physical hardship. They were released at the end of the war, the vast majority in April 1939 and the rest in August. In Gandesa we also gathered recollections of people who saw the captured brigaders, who were imprisoned in a building where women and children came to see them. They remember that the volunteers looked very tired and dirty, and only asked for water and cigarettes. In Corbera d’Ebre, locals showed us a house in whose cellar some brigaders were held. They were taken outside through a back door in groups of two and then shot.

Once a village had been occupied, Franco’s Army was under orders to bring people back in order to keep them under control. Because the villagers returned to their homes again we also have information about what happened in the towns. The people of Corbera d’Ebre showed us the place where the executions took place: just outside of the village, a place known as Les Eres. We were told that sometimes the Nationalists made the brigaders run before being shot. They only wore underwear because they were stripped of all their belongings. After being shot they were buried on the spot, and there is no reason to doubt there volunteers’ remains are still there. The locals explained that while those who died far from the village were buried where they fell, those who died closer were loaded on mules and then buried in mass graves in Les Eres. Who buried them? Villagers, particularly those labeled as “Red”. We have the valuable testimony of a local man who in 1938 was 16 years old and is still alive, with his memory intact. When his father was called to be part of a group of diggers, he volunteered to replace him. He took us the exact place where he dug a grave for a brigader. He remembered that the man was very tall, with brown hair, wearing only his underwear; it impressed him to see the corpse lying there. He dug a trench about one meter deep. The undertaker of the town was the person who threw the body into the grave and another group covered it with dirt. While we took photos and marked the site with the GPS, the villager told us that as far as he knows the brigader is still buried there. A chill ran down our spines. How many brigaders must still be buried in the area without even a single mark that remembers them?

We must not forget those who were drowned in the River Ebro. Although volunteers could have managed to escape the numerous Fascist patrols between Corbera d’Ebre and the River Ebro, those who reached its shores found no bridges or boats to cross it, as the Republican Army had blown up the bridge of Mora d’Ebre in the evening of April 2. Many Lincolns from the cities, who had never learned to swim, ended up drowning.

We are compiling a list of those killed during those days and so far we can say that about 183 volunteers died during those early days of April. There is nothing to remember those men. Only in Gandesa there is a plaque at the cemetery in memory of a brigader, Kenneth Frederick Nelson, 22 years old, who was born in Colorado and came from Seattle.

Our goal in doing this work has been to remember this frightening episode, not only to educate Spaniards about the tragedy of our Civil War but to also honor the international volunteers and give them back their dignity.

Anna Martí Centellas was born in Terrassa (Catalonia, Spain) in 1970. She works in a national park and has long been fascinated with the English-speaking members of the International Brigades. She will be speaking about her research at Batea on Saturday March 30, 2013, on the eve of a commemorative march. See pdlhistoria.wordpress.com for further information.

![11_0276s_A chabola [shelter]_Mar 38](https://albavolunteer.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/07/11_0276s_A-chabola-shelter_Mar-38-300x222.jpg)

Congratulations Anna, on your publication and getting your ‘BY line’ at last. A very interesting and poignant piece of work. Excellent English and well researched. Hope to be at your talk in March 2013!

Know your history, learn your history, understand your history but most important of all never ever forget your history. Your research will be an inspiration that others will follow. For far too long the history of the sacrifice of the volunteers of the International Brigades in the defense of the Second Republic has been hidden from the people of Spain.

Their story must be told again and again and to that end you have made a magnificent contribution.No pasaran.

That was a fantastic article. I really enjoyed it.

Joe

Congratulations on a very good account of what is, for too many, forgotten history. I hope it serves as a model for other accounts that will keep the Spanish Civil War’s lessons alive. The then and now photos make the older photos seem like yesterday.

Anna, thank you for this great history. My Father, who had been reassigned to the British Battalion for the retreats, left a letter to Art Landis in Art’s files at the Tamiment. In it he asked about where the Lincoln’s ended up in the retreat because he was totally separated from them. But your story pinned down the date and time for me when he crossed the Ebro since he said he crossed about 20 minutes before they blew the bridge at Mora d’Ebro.

I’m looking forward to joining Alan Warren and others next March to commemorate the 75th anniversary of the retreat.

Ray Hoff (father was Harold S. Hoff, Special Brigade Machine Gun Company w/ Jack Cooper at the end at Gandesa)

Acabo de subir un ensayo sobre Fausto Villar, ver este enlace: https://sites.google.com/site/gceformulario/4-km-en-belchite

Eduard Muscala is in my mind since that I read your name in the wall of the chapel of my village, and I didn´t understand what it meant, I was a child.

You are invited to my village.

If at all possible I would like to find my Grand Uncle Albert Foucek who may be (?) among the execu.ted prisoners

Dear Mr. Cope,

If you would like to contact me, this is my email: annataru@hotmail.com

I am sorry to tell you that, although there is a list of the missing and dead brigaders, there is not a list of the executions. Nationalists didn’t keep a list of the brigaders shot. Your Grand Uncle is not among that list of the dead and missing but I had his name among the dead at that period, although I think he was with the Mackenzie-Papineau battalion.

Thank you for writing this in such great detail. My uncle, Maurice Friedman, was listed as missing in action at Batea on April 1, 1938. My mother, his sister, always understood that he died on April 2, 1938 at Gandesa. I know from my experiences with Alan Warren looking around that area and listening to an account of what took place, that the exact date and circumstances of Maurice’s death are mired in the chaos of the Great Retreats. It is enough now for his remaining family to have an idea of approximately where he fell and the kind of action he was involved in up to the last. My mother inscribed a book of his, “The Literary Digest 1927 Atlas of the World and Gazetteer” with this phrase: “Maurice Friedman Died April 2, 1938. Democracy, so that Spain might live.”

[…] https://albavolunteer.org/2012/07/in-the-footsteps-of-the-lincoln-washington-battalion/ […]

[…] https://albavolunteer.org/2012/07/in-the-footsteps-of-the-lincoln-washington-battalion/ http://historycompany.co.uk/2012/09/05/what-franco-wanted-us-to-see/ […]

My mother’s uncle, the man I was named after, Robert Rubin Weber, was killed near Gandesa during the retreat. https://alba-valb.org/volunteers/robert-r-weber/

I mention this in my book “Bobby in Naziland: A Tale of Flatbush.” When I was writing the book I knew none of the details, only that he was reported MIA. The ALBA site now has his passport photo. Today is the first time I’ve ever seen his photo.

My uncle, William Madigan was a New Zealander serving with the ALBA and was killed probably during the retreats. We believe he was a machine gunner and had been wounded during the fighting around the “Monastry” outside of Belchite. After hospitalisation he returned to the front and we know nothing more about his fate.

I was put in contact with Alan Warren in 2015 and was honoured to be present at the installation of a plaque bearing William’s name (among others) at Camposines.

I would dearly love to have more concrete information on the place and date where William fell if at all possible.

Regards

Dave Madigan