The Civil War Begins: Savage Coast (Costa Brava)

Edited by Rowena Kennedy-Epstein

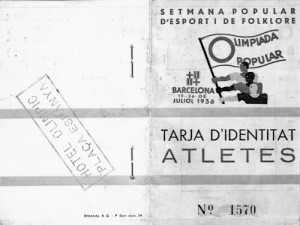

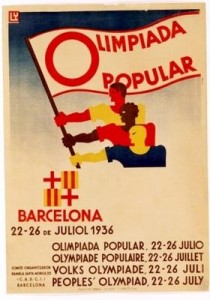

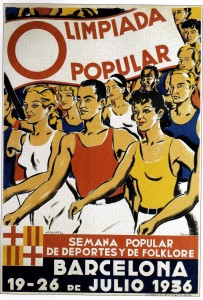

On July 18, 1936, at the age of 22, the American poet Muriel Rukeyser (1913-1980) traveled to Barcelona, on assignment for the British magazine Life and Letters Today, to report on the People’s Olympiad (Olimpiada Popular). An anti-fascist alternative to Hitler’s Berlin Olympics, the popular games were canceled when the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War interrupted the opening ceremonies. Rukeyser was on a train with the Swiss and Hungarian Olympic teams, as well as tourists and Catalans, when it was stopped in the small town of Moncada as the civil war began and a general strike was called in support of the government.

The passengers were stranded for two nights as the people of Catalonia defended themselves and their government from the military coup, the fascists escaping through the hills surrounding them. Rukeyser arrived in Barcelona just as the city established “revolutionary order” and witnessed the first militias marching to the Zaragoza front. Though she was evacuated only a few days later, Spain would prove to be a profoundly radicalizing and transformational experience, one she would describe as the place where “I began to say what I believed,” and as “the end of confusion.”

Rukeyser would write about the Spanish Civil War for over forty years, in nearly every poetry collection, in numerous essays, and in fiction, weaving the events of the war and the history of anti-fascist resistance into an interconnected, multi-genre, and radical 20th-century history. The most complete rendering of her experience is her unpublished, autobiographical novel Savage Coast (Costa Brava), which she wrote immediately upon her return to New York City in the autumn of 1936 and edited throughout the war. The novel, which remained unfinished in her lifetime, with her last editorial choices in pen, will be available for the first time from the Feminist Press in January 2013.

The passage below is the first excerpt of the novel to be published. The scene begins after two precarious days in Moncada, all communication cut off by the general strike and the fighting. For the foreigners stranded on the train, the only sign that the government still stands is the intermittent radio. Helen, the protagonist, her lover Hans, a long distance runner and political exile from Nazi Germany, and an American communist couple, Peter and Olive, whom she befriended on the train, have watched the collectivization and defense of the republic with solidarity and excitement, hoping to get to Barcelona with the Olympic teams.

I have made the changes indicated by Rukeyser in pen. Other than that, the text is printed as the author left it.

—Rowena Kennedy-Epstein

They were speaking with difficulty, as if they had been drinking for a long time. As they paid for the food, little coins rolled and fell, and they slapped their hands on the money drunkenly to keep it still. They were surprised at the shifting darkness in the dim room, the immense rolling distance from the table to the door, the faces (like weird fish shining deepseas down) of the girls.

In the street, the elastic waves of sunlight arrived in a flood, shocking them, beating at the temples, insistent.

They looked up toward the church. Butcher’s closed; fruit store, closed; grocer’s closed; a block away, though, a crowd had gathered, filling the street-corner.

They looked up toward the church. Butcher’s closed; fruit store, closed; grocer’s closed; a block away, though, a crowd had gathered, filling the street-corner.

“Probably opening houses,” said Olive.

Helen wanted to go up. She remembered their retreat from the church the night before. All these houses must be opened now, she thought. “They must have started this section, last night,” she reminded Olive. “The boys were ramming in the door.”

They passed the door on their way up. It was broken, half-open, lettered C.N.T., F.A.I. Through one smashed shutter they could see the overturned tables, ransacked shelves, broken crucifixes of the parochial school.

The crowd was standing still. It was not carrying guns. Only two men at the corner, and one who stood in the middle of the crossing, had rifles in their hands.

Across the street, a long robin’seggblue bus stood surrounded by people who put their hands on the bullet-scratches, traced the long roads cut in the enamel with their fingers. Two boys with a can of white paint were daubing large letters on the snub hood and on the rear of the bus.

GOBIERNA.

“That must be the Government bus for the Swiss,” said Helen. There was a spick round hole in the windshield. The heavy glass caught sunlight on the hole-rim; bright stripes of light ran outward in a sunburst.

Peter followed her startle, calculating. “That couldn’t have missed the driver,” he remarked.

The boys went soberly ahead with their lettering, and the crowd, pressing about the truck, commented, told stories about the road, crossed and re-crossed, shouting to women leaning from windows.

Helen looked at her hand. On it was printed, in a violent after-image, the bullethole and glassy light.

But the crowd was backing, to clear the street. A car cruised down and guns stood out from every window.

The man in the road raised his clenched fist.

He wore a red band around his arm.

The driver’s fist was already held out of the window, his elbow resting on the windowframe. And all the other men, in the car and on the streetcorner, raised clenched fists.

In a wonder, as if the car had come to save them, as if this were her dream that she was dreaming now, Helen raised her arm and shut her fist.

“The first we’ve seen!” Said Olive. The tears rose to Helen’s eyes, sprung; and stopped.

“Long live soviet Spain,” Peter answered, completing her thought, all his wish clear in the words.

Order, like a steady finger, covered the street. The crowd looped back, remaining on the sidewalk. The second car came, lettered P.C.—Partit Communista—and the shouts and fists came up as it passed. The long black car was full of men, and the driver and a woman sat in front, smiling and holding their tight hands to the people.

Helen turned to Peter, “How beautiful it is now!” she said. She looked as if she had just slept. She found the same safety in his face.

“Now it’s all right,” he answered, and took her arm and Olive’s. They walked to the edge of the crowd, and cars kept passing like shouts, with lifted fists. Another man stood on the curb, stopping the cars for passwords. The last one started in second, clashing its gears, hurrying down the road. He stepped back and smiled at the Americans. His eyes were the absolute of black, night tunnels of distance. They smiled.

Peter stopped. “Communistos hoy?” he asked.

The man’s eyes slid smiling. “Si, compañero,” his proud singing voice rose. “Today and Tomorrow.”

“It’s later than we think,” Peter quoted.

Helen’s face flared. “I want to go back,” she insisted. “I want to tell Hans.”

“Yes,” said Peter. “This is all right.”

“Now I’d like to get to Barcelona,” Helen pushed out. “This is what it meant. I’d like to see a city like that,”

“It’s not like France, is it, Peter? You know,” said Olive, abruptly, “it’s the first time this has seemed at all real to me. It’s the only thing I’ve felt, really—except for that moment when they shut the door this morning.”

The hurrah of gunfires started in the hills, and ran for a minute.

One of the bitches, the sickly one, ran up the station street wagging her hand in the other direction.

“Down there,” she panted, wagging. “The Swiss are leaving—”

They started to run down the street. Peter was alongside the bitch, he could see the sad bruised eyes were swollen, the wrinkles were almost erased.

“Upset?” Peter ran alongside.

“Well,” she said, and the fret and suffering obscured her voice, “it’s the Swiss—they’re getting out of this hellhole.”

Helen slowed down with them. The words fell icy on her, she had moved so far from that state. Now, with a shock, she saw the sick, pathetic woman plain, and behind her a whole intelligible world she melted into, like a weak animal protectively colored. And with a counter-shock, Helen remembered her own impatience, a tourist spasm, when the train had for the first time stood interminably long in the way stations. The words had wiped that frantic itch for comfort away. But she was, in mood at least, prepared for GENERAL STRIKE, and it could change her effectively at once. The bad leg was all that stood of the past now. There was no time for it. It was later than that. Nothing but the knot of Swiss, waiting on the corner, their battered suitcases and knapsacks heaped ready.

. . . .

The truck was ready, full of Swiss, backed to the station, engine running. The automobiles were lined up. The chorus filled one and left room in the other for the French delegate and his secretary. Another open truck stood empty.

A tall yellow-faced man stood beside it. “This is for anyone connected with the Olympics, and then for anyone who cares to try the drive with us,” he said, in French and English. His long face was like intellectual metal, yellow and refined sharp; and further lengthened by the high V of baldness which ate into the fair hair, baring the skullridges.

“Who is coming?” he asked. The truck began to fill. Olive was on its floor as the suitcases were thrown in. “Is there much danger?”

The tall man looked up. “There is steady fighting; but we have a guard.” A thin boy with a white handkerchief around his head climbed in. He smiled with all his teeth, he patted his rifle. Olive made room for him, and he took his place at the front of the truck, leaning on the roof over the driver.

“Then it can’t be like this,” she said, and called to Peter and Hans to stop loading.

Helen climbed in. She pulled the suitcases over from the center of the floor.

Olive was busy. She was sure now. She up-ended all the bags.

“Stack them around the outside,” said Olive, setting them straight and close. “We’ve got to have some walls. We’ve got to have some order.” Her face was clear and active at last.

They built a wall of baggage for the truck on both sides. In front, valises and the driver’s box reached breast high. Olive was in charge, she moved everywhere, quickly, with Helen.

“All right,” she said. The tall man nodded, and helped the others in. The bitches came running. Mme. Porcelan, attended by the pock-marked Swiss, brought baggage. They climbed in.

“Ready?” asked the tall man in a father’s voice.

The driver was ready. Another guard climbed into the seat, holding his gun out the window. From the truck, the muzzle could be seen, and the oily gleam of the barrel.

“Slowly, through the town,” the tall man said.

Hans and Helen were beside the guard. He reached out behind the guard and took her hand for a moment.

The boy smiled and looked at his gun. “Everyone is safe,” he said. He was very handsome.

Peter and Olive were crushed against them. Helen was glad to feel their weight. They are very good friends to have, she thought. The space left between the walls of suitcases was narrow.

The truck started, blowing its horn. As it turned down the main street, Helen could see the women who had listened to the yodeling, standing in the same place. Hans’s fist was up, saluting the town. She clenched her fist, and the women in the street replied. There was a flash of vivas, and the little tunnel blacked out the street.

Their truck led the way to the top of the hill. Halfway up, at a sharp curve, the town petered out in a ravel of old houses and meat-stores. The truck made a half-turn, backed, and stopped.

“God!” said Peter fiercely, “what’s the matter?”

“He’s just turning,” Olive suggested.

“He could make the turn—” said Helen.

The street was barred by children; they leaned against the walls, dodged across the road, sat on the curb. Their streaked faces were full of curiosity, and all their heads turned together like newsreel heads of tennis-match spectators, as horns began to blow. The two cars and the other truck pulled up the hill.

The street was barred by children; they leaned against the walls, dodged across the road, sat on the curb. Their streaked faces were full of curiosity, and all their heads turned together like newsreel heads of tennis-match spectators, as horns began to blow. The two cars and the other truck pulled up the hill.

“We probably all have to start together,” said Peter.

The yellow man got out and called the drivers together.

His face was the most disciplined face Helen had ever seen, one end of civilization. Down one temple the skin was thin, as if an old burn had left it fragile, and the blood showed dark beneath. He was speaking to the drivers in an extreme of conviction.

Peter pulled her elbow. His face had knotted with the delay, and he was contagiously wound tight. The three of them felt undercut and excited by the same shock of drunkenness they had felt in the café.

“Look at the baby,” he said, as if he were telling a joke.

She followed his finger. The little boy was no more than two years old, and was sitting on the curb. He was staring at the trucks and masturbating absentmindedly.

“Infantile—Infantile—”

“Auto-eroticism,” Helen supplied.

“Not at all,” he said gravely. “Vive le sport!”

Olive howled and the athletes turned in surprise. The yellow man looked up as he finished speaking to the drivers; he crossed to the space in front of the trucks, and held up his hand. The thin lavender mark was streaked, distinct on his temple.

“We are starting now,” he said in a direct, high voice. “We know we can rely on you to work with us, so that everything will go well. From our reports, the road should be well-guarded and quiet now; but you must remember to watch constantly for snipers, and to duck if the truck is fired at.

“Above all, we count on you to maintain with us discipline and proletarian order. If there is too much trouble, we will stop on the way; but, whatever happens, the strictest order must be kept. The guards are not to fire until it is necessary; until they see”—he pointed to his own— “the whites of their eyes.” He looked at the passengers, and raised his fist.

“To Barcelona!” He was in his car, leading the way down the cryptic road.

Their fists came up. Peter danced from one foot to the other in an anguish of excitement. He laughed and exclaimed, pompously and dramatically, in the voice of Groucho Marx: “Of course they know this means War!” Olive and Helen laughed with him in one long shriek. The other truck was starting.

Everyone stopped laughing and looked down the road. The red hill stood above them, the pylons marched over it; it was a different view of the cliff, and the profile of the red sand-cut was clear for the first time. The hill looked entirely new. This was unknown country. The truck got underway, shifting high immediately, racing full-speed and roaring into the open road.

. . . .

Far down the hill the tracks extended, minute and vulnerable. The train stood grotesque, stiff, the only motion being the thin black fume above the waiting engine. The fume rose straight and sacrificial in the still air.

But up here, faces were whipped by wind, beaten with the speed of flying. The open truck ran out into wide country. The high significant hills stood: the farms waited: only the truck raced checkless on the roads.

To those faces, upon those eyes, it was the land racing, the world, high, visionary, unknown.

They were tense, held high, the eyes seemed wider set, like the abstract wide eyes of dancers. All the faces looked up the road.

On either side, the long grass, the wide farm-swathes, the walls of farmhouses.

The truck stopped where a car was headed across the road. The driver showed his pass-slip to the guard, a woman in overalls and rope sandals. A band about his forehead meant a suffering wound or a badge or a notion to keep the hair back, it matched the band that was around the head of the young guard standing in the truck.

Then they knew they had not reached their full speed. That barrier marked the town limits; now they were entering contested country.

The guard sitting with the driver leaned out and shouted up a word of encouragement. Then they let the motor out. The illusion of great speed was partly the product of a fierce dream, standing on the leaping floor, holding to each other and the walls, receiving the iced wind on skin, used to the stagnant heat of the trains.

But the truck itself was moving fast.

At the right, the blue-and-white Ford sign was a grotesque. And here, along the farmwalls, bales of hay, stacked solid for protection.

The overturned wagon at the door, its front near wheel still spinning.

The black bush on the hill.

Barricades.

And all these rushing past, the speed of fear, the hands in the doorway, the fists on the hill all raised, clenched, saluting.

Put on coats, they thought, the cold will strike you dead! Watch the road, the black eyes are wild concern, the fingers loose the trigger to point to the wild eyes, crying with that pointed gesture: Watch for guns!

On exposed rides, passing the pale houses, the tiled roofs, red now, now darker, shadowdark against the low sun, fear passes, the faces clear and become fresh and happy, filled with this youth that speed gives, the windy excitement of fear, the exploration opening new worlds with a lifted arm.

A quarter of a mile down the road, they saw the men waiting for them.

And all the sky drawn colored toward the sun.

The men grew larger.

Racing down the stretch, the fields slanted away from them, precious and quickly lost, the pastures gleamed under rich lights like grass-green jewels, the house stood lovely and forbidden.

The floor of Europe leaped shaking beneath their feet.

The men stood before them, signaling. Guards.

“Slowly, now. Watch closely.”

Air relented on the cheeks. Everything was displayed clearly and minutely, even during speed, standing so high; and now, the dust on the roadgrass, the purpleflowered fields, farmhouses, mules, were rotated past methodically. The railway tracks slanted across their view again, and the ominous culvert reared above them, broad and solid stone.

The guard raised his gun to his shoulder. He pushed the handkerchief tight around his head.

Darkness ran over the truck safely. They were on the other side, where the road was fenced with steep sandslides.

The flaring trees at the top. The deathly bushes, yard-fences, a man sliding down, his legs braced stiff, come down to take the pass.

And another clear run, the road straight, the country-side changing, farm giving way to smaller garden, large estates replaced by factories, closed and empty, but well-kept and waiting as on holidays.

So many windows.

Watched the walls as they had watched the bushes. Each thought: guns! There is no way to watch, raking a wall of windows, for a narrow bore. Instinct, the pure ruler quality, wipes away remembrance, the countryside of the mind replaced from a moving car. In a shock of speed.

They watched; waited for city.

A nightmare gun-bore stood black and round in the brain.

They had expected city.

They saw nothing but street: a passage, impossibly long, bending from country road, where the barriers were far placed and long dashes could be made, to an avenue through glimpsed suburbs, and now this, which must be city, if the mind were free to look, but which seemed only street, broken by barricades at which the truck stopped, and the fringes could not be noticed, the faces, the piled chairs, corpses of horses. Then a spurt of speed, wind, and tight hands; and immediately, a gap in the road, blind; after that second, recognized.

At such moments, the sides of the road may be discerned.

The sidewalks, the rows of houses, blocks of lowlying buildings

And ahead? A wall.

The passengers drew in their breath as the men before it turned, the levers held in their hands, and the man with the gun came forward. For the levers chopped the street. The street was lifted to make this wall. The cobblestones were built high.

On the barricade, the red flag.

Again, as the guard stopped them with his fist, their fists came up.

From then on, the fists remained high.

The streets were those of an outlying district. Every man on them raised his fist, timed to come up as the truck passed.

The guard kept his gun up.

Now, from the windows, white patches flew, hanging truceflags of white, lining this street which was taller as they raced deeper into the city.

The barricades, were up.

The barricades, recurring every hundred yards. Here, a young soldier, helmeted, behind a machine gun, trained on the highway.

Speed, two minutes, blindness, the road.

Another stop; another wall, a glimpse of street-corners.

And the children who played, the families who passed walking, all their fists lifted. The movie house on one side; the sudden heat blown from the church burning on a square. The piles of firewood heightened in flame: vestments, statues, gaudy cloth, images to be carried head-high.

The truck swung down a wide avenue, and far to one side, the quadruple black-and-white spires of the Sagrada Familia rose intact.

Stores, promenades, evening.

And everywhere, the million white, the flags pendant from the windowsills, the walker in the street who lifts his hand.

The hands lifted from the truck, held tight and unfamiliar in perpetual sign.

They lost themselves, travelers exposed in this way, totally unforeseen, strange. This was a city they had read on pages in libraries and quiet rooms, leaving the books to find a hard street, bitter faces, closed silent lips at home.

But there the boy stood, his face raised in recognition, his hand, like all theirs raised.

The car swung ahead.

The bullet cracked.

From the confusion as they all bent, head and shoulders low in a reflex of dread, Helen looked up to Hans’s unmoved head, either risen immediately or never changed.

The truck wheeled sharp, on two wheels, to the left, and they caught at arms and hands in confusion, straightening now, recovered.

Avenues opened wider and wider, the plane-trees, the oranges, the palms. Cars passed them now, and each time they blew, One-two-three, stopping to race the cars loaded with guns, spiked with guns. Each car carried the white letters of its organization: U.G.T., C.N.T., F.A.I.

The chopping of pavingstones was loud at the streetcorners.

And now, down the long Rambla, past riddled barracks, shell-torn carnivals, bomb-pocked hotels. The dead cafés, their chairs piled on the sidewalk, before the drawn steel curtains.

Wind, fast wind increasing; the long view of a brick-orange fortress, impregnable and high. The high column, the long blue stripe of sea.

And the truck turning.

Avenues opened into a great circle, a public square, mastered by two tall pillars, holding subway stations, statues, overturned wrecks of cars, candycolored posters, full-rounded walls, cafés, the guarded front of an immense building out of which streamed warmth and talk, files of young people streaming.

The truck circled, slowing.

It stopped at the building’s entrance.

The travelers jumped one by one.

Hans dropped catquick down, and swung his arms up for Helen. She placed her hands on his cable wrists, and jumped. It was then that the four pains in the right palm were noticeable, and, looking down, the four blood-dark crescents were seen, the mark of the clenched fist, clutched during the voyage.

A guard in a blue uniform, rifle slung at his back, was standing with them.

He smiled at the hand.

They answered.

She asked, “and this?”

The building was large. It streamed warmth.

He looked at the travelers.

“Hotel Olimpiada.”

Rowena Kennedy-Epstein, editor of Savage Coast (Costa Brava) (Feminist Press, 2013), is a Ph.D. candidate in English at the CUNY Graduate Center, where she is completing her dissertation on Muriel Rukeyser and the Spanish Civil War.