Anatomy of a Lie: The Death of Oliver Law

Editor’s Note: This is an abbreviated version of a long article (and documentation) published in the on-line journal Reconstruction vol. 8, No. 1, February 2008, at http://reconstruction.eserver.org/081/furr.shtml

Oliver Law, the first Black American to command white troops in battle, was appointed on July 5, 1937 as commander of the Abraham Lincoln Battalion. According to eyewitness accounts of men under his command, Law died a hero’s death leading a charge against Francoist forces on Mosquito Hill at the Battle of Brunete on July 9, 1937.

In 1969 a story of how Law died was published that diametrically contradicts this account when Cecil B. Eby of the University of Michigan, wrote the following passage in his history of the ALB, Between the Bullet and the Lie:

“The ‘anti-official’ version claims that a Negro machine-gunner swooped forward and performed a joyous dance of death around the body. Others spat and urinated on it. Law’s body was left where it had fallen and was bloated by the sun into a horrible balloon.”

A note at this point expands this “anti-official version”: “Some veterans aver that the bullet that killed Oliver Law was fired by a disgruntled Lincoln who was convinced, after two previous ambushes, that Law had to be removed from command before he got all of them killed.”

In his 2007 book Comrades and Commissars: The Lincoln Battalion in the Spanish Civil War, Eby’s account of Law’s death reverses the order of these two versions:

“…Law went down with a bullet in the belly. He died within a few hours. There are two irreconcilable accounts of what followed, one that claims he was shot by one of his men, disturbed by his poor leadership–Law had already led his men into several ambushes–and the other in complete denial of this.”

This article will, first, investigate the evidence supporting what Eby calls “both versions” of how Oliver Law was killed. Is the evidence for each of these diametrically opposite accounts so evenly balanced that no conclusion is possible?

Though he used the phrase “some veterans aver…” in 1969, Eby has since admitted that he has only one source for this story: William Herrick, one of a small group of Lincoln veterans who became disillusioned with the American Communist Party. Eby and Herrick met in Spain in 1967 and remained good friends till Herrick died in 2004.

Herrick’s version of Law’s death presents a number of interesting problems. For one thing, Herrick wrote it first in 1969 in fictional form, in his novel ¡Hermanos! He did not write it down in non-fictional form until 1983; for publication until 1998. But Herrick told the story orally many times.

Herrick’s fictional version is very similar to another fictional version published a decade earlier. In 1959 Bernard Wolfe published a novel titled The Great Prince Died. A former “secretary” to Leon Trotsky, Wolfe luridly depicts the killing of an incompetent black officer by his fellow Lincolns. At the back of the 1975 reprint of Wolfe’s novel (retitled Trotsky Dead) we find the following note:

“The Sheridan Justice incident is not an invention. Such an ill-equipped American black, by name Oliver Law, was promoted to an important command in the Abraham Lincoln Battalion in Spain, and was killed in an insane orgy by some of his overpressed comrades.…It was told to me by William Herrick, himself a veteran of the civil war, and subsequently recorded by him in his excellent novel about the Spanish tragedy, Hermanos (New York, 1969).”

Thanks to this note we can be certain that in the 1950s Herrick was telling a version of Law’s death very different from the account he gave Eby between 1967 and 1969, when it appeared in Eby’s book, and he was telling it not as fiction, but as what had really happened.

To Wolfe, and in his own novel, Herrick described Law as encircled by a number of the men in his command, brutally taunted, gut-shot, and left to die slowly and painfully as the men looked on. In Eby’s 1969 account, which he acknowledges he got from Herrick, a group of men participate in celebrating Law’s death and in desecrating his corpse. But this “group action” takes place after Law is killed, while the murder itself is done by only one of the soldiers. In Eby’s 2007 account the “group action” has vanished and the killing of Law “by one of his men” is, for Eby, the canonical account, the only version of Law’s death in his book.

Herrick recounted his version of Law’s death in print twice. In the July 22, 1986 edition of the Village Voice Paul Berman published the transcript of an interview with Herrick. This version is inconsistent with all the previous ones: Herrick’s and Wolfe’s fictional accounts, and Eby’s 1969 version (as well as his 2007 version). The second and last time Herrick related this story in print was in his 1998 memoir Jumping the Line.

Herrick says he heard this story at second hand during a drinking party from the men directly involved. So there are two distinct stories in play: that of the “drinking party” and the story of Law’s death that Herrick claimed to have heard there. So Herrick was telling not one, but two stories.

The Village Voice interview had created a sensation and became a story that any historian of the ALB had to grapple with. In The Odyssey of the Abraham Lincoln Brigade (1994) Peter Carroll went to some lengths to check all versions of Law’s death. Carroll concluded Herrick’s account was false.

In his final version of 1998 Herrick both gives and withholds details. Herrick refers to “that awful tale”…“this harrowing tale.” But he doesn’t tell the reader which version of this “tale” Herrick means.

It is still a “group action” about “how they’d killed Oliver Law.” But there’s no question any longer of one man shooting Law and the rest “dancing” around his body, etc. “They” –the group–killed Law. For other details we will have to refer to some earlier, known version of the “tale.” But which one?

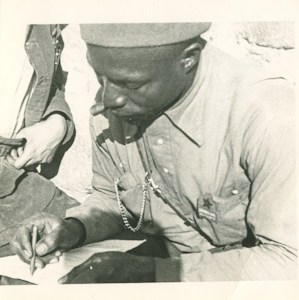

Water carriers (previously misidentified as Oliver Law; Tamiment Library, NYU, ALBA Photo 184, Box 1, Folder 34)

Herrick agreed with other witnesses who angrily reject Herrick’s version that Law was killed in battle at Mosquito Crest. That is, Herrick silently withdrew his earlier account of Law being gut-shot and taunted by his killers while he slowly died. He also tacitly altered his Village Voice account in which the fighters were only in “battle position.” This account leaves no room for a story Herrick had told Eby, of “a Negro machine-gunner”– this could only have been Doug Roach–who allegedly “swooped forward and performed a joyous dance of death around the body.” Other accounts of the battle of Mosquito Ridge leave no possibility that anybody was “dancing” around Law’s body or anywhere else.

Herrick finally reveals the names of three of the alleged participants in Law’s murder. By 1998 all were dead: Doug Roach in 1938, Joe Gordon in World War II. But Peter Carroll had interviewed Hy Stone in 1990.

Herrick wrote in 1998 that Mickey Mickenberg knew the story as well as the identity of the Lincoln who had shot Law. Herrick omitted this from his memoir but told Cecil Eby that this was Hy Stone. Herrick also affirms that Bob Gladnick learned the same story of Law’s death from Joe Gordon.

Mickenberg died in 1960. Bob Gladnick, also dead by 1998, had written about Law to Cecil Eby in the 1960s, and had written a letter to the Village Voice in 1986 in support of Herrick’s interview. But he never confirmed Herrick’s claim that he too had heard the story of Law’s death from anybody.

The “officer’s runner” Herrick referred to must be Harry Fisher, who called Herrick’s story a lie. Rather than come to the defense of his own story, though, Herrick backed away from it: “I wonder if he [the runner, i.e. Fisher] had a criminologist with him at the front to examine Law’s body in order to determine where the bullet came from.”

That is, when confronted with eyewitness accounts of Law’s death Herrick responded: maybe one of the Lincolns had shot Law. He did not retract his claim that he had heard the “tale” of Law’s assassination by other Lincolns. But Herrick tacitly acknowledged it was false. By reducing the question of how Law was killed to one of where the bullet that killed Law had come from, Herrick tacitly conceded that the story he had told Wolfe of the “group action” did not conform to the facts.

Variations in Herrick’s “tale”

Eby insists there were no changes in Herrick’s story over the years. Eby is definite that Herrick told him it was Hy Stone who had admitted shooting Law. Aside from Stone, only Roach and Gordon were present at the “drinking party” (Eby’s words). Herrick also told Eby that Doug Roach said he had pissed on Law’s body.

Interviewed by Peter Carroll on August 23, 1990 Herrick added that it had been Joe Gordon who pissed on Law’s body. Herrick told Carroll that Joe Cobert knew about this story too, but was not certain whether Cobert had been present at the “group action” when Law was killed. Eby says Herrick had not named Cobert to him.

For some reason Herrick did not tell Carroll that Hy Stone had admitted being the one who had shot Law. According to Eby Herrick had been very definite about this.

Hy Stone and Joe Cobert were still alive in 1990. When interviewed by Carroll on November 28, 1990 Stone denied everything Herrick had said. “Of course not.” “I was not there” (in the room with Herrick and the others at Albacete). “He’s crazy.” “Never saw him in Spain.”

Carroll interviewed Joe Cobert on January 20, 1991. Cobert denied being in any hotel in Albacete with Herrick and the rest, telling Carroll he had “a feeling he [Herrick] would make anything up to discredit us.”

The results of our inquiry to this point are as follows:

- “Herrick’s story” is really two stories: the “tale” of Law’s death; and story of the “drinking party.”

- Faced with eyewitness accounts to Law’s death Herrick himself backed down from the “tale” as he claims he was told it. The “tale” changed and, finally, shrank almost, but not quite, to disappearing.

- Neither Mickenberg and Gladnick, who Herrick claimed could confirm the” tale,” mentioned it.

So the “tale” is false. But did Herrick really hear any version of this story at all? Did the “drinking party” ever take place? Or did Herrick “make it up”? Hy Stone, whom Herrick insisted was there, denied any knowledge of it. Joe Cobert also denied it. The other men Herrick claimed were present – Doug Roach and Joe Gordon – were both long since dead.

Eby repositions Herrick’s “tale” as the “canonical” account. But the truth is just the other way around. While there is no evidence whatever to support Herrick’s “tale” there is a great deal of evidence to support the version in which Oliver Law died heroically leading his men into battle at Brunete on July 9, 1937.

The Nation published Dave Smith’s first-hand account of Law’s death in 1998. Peter Carroll also interviewed Smith on several occasions. On May 3, 1998 Carroll’s notes say Smith described “small entry wound on [Law’s] chest. Then after cutting open shirt, finds larger exit wound in back.”

Mel Anderson, another Lincoln interviewed by Carroll, said he had been in a machine gun company at Brunete directly behind Law. Anderson witnessed Law’s being shot and said it was “ridiculous” to think he could have been fragged by one of his own men. “The fire was tremendous.”

An account written down at the time of or as near in time to the event as possible is the best evidence, as it will, at least, not reflect the biases of a later period. Memory, a creative and recreative faculty, will have had less time to alter what the senses originally perceived.

In a letter to Carroll of April 11, 1991 Herrick stated: “I got my version from primary sources, Gordon, Roach, Stone, and later Mickey Mickenberg. And I received my version within a month after the event. It’s either I’m a liar or Stone is a liar. Take your pick.”

There is less here than first appears.

As we’ve seen, by 1998 at latest, Herrick had backed off any claim that the “tale” of the “group action” was actually true. But no one can be a “primary source” for an event that never took place. So the men Herrick claimed had told him the “tale” of Law’s murder weren’t “primary sources” at all–even if they really told Herrick this story.

Furthermore, Herrick claimed he had “received” his version “within a month after the event.” But Herrick never had any such single “version.” He told multiple, contradictory versions. Herrick did not record “drinking party” and the “tale” supposedly told during it “within a month after the event.” The earliest account we have of this “tale” is Wolfe’s fictional published in 1959, who says he got it from Herrick. This was 22 years after Law’s death at Brunete in 1937.

Herrick himself did not record it for publication until the Berman interview in 1986. Even then he referred to it only in very general terms. Herrick did write it down for Victor Berch in 1983, though no version of his appeared in print until Jumping the Line in 1998. Moreover, all these versions differ significantly from one another.

But there is one account of Law’s death written down within less than three weeks “after the event.” In a letter to his family of July 29, 1937 Harry Fisher wrote:

On July 9, we went over again. It so happened that the fascists had attacked too. We were about a thousand meters apart, each on a high hill, with a valley between us. The Gods must have laughed when they saw us charge each other at the same time. Once again Law was up in front urging us on. Then the fascists started running back. They were retreating. Law would not drop for cover. True, he was exhausted as we all were. We had no food or water that day and it was hot. He wanted to keep the fascists on the run and take the high hill. ‘Come on, comrades, they are running,’ he shouted. ‘Let’s keep them running.’ All the time he was under machine-gun fire. Finally he was hit. Two comrades brought him in spite of the machine guns. His wound was dressed. As he was being carried on a stretcher to the ambulance, he clenched his fist and said, ‘Carry on boys.’ Then he died.

The authority of this document cannot be impugned. There is no other account, either corroborative or contradictory, written down any time near the event. Though it agrees completely with Dave Smith’s account it is of greater authority because it was recorded by an eyewitness within a month of the event.

This letter was published in 1996 in a book which Eby cites twice. So why didn’t Eby use Fisher’s letter? Did his friendship with Herrick and fervent anticommunism lead Eby to neglect an historian’s commitment to objectivity?

What Eby called “the official version” is an eyewitness account of Law’s heroic death. Herrick’s account is hearsay, Herrick’s account of what he claims he heard others say.

So there are not two versions of Law’s death, each one “sworn to” (Eby). The only thing Herrick could “swear” to was that he heard the story, not that the story was true.

What Herrick “swore” to was that he had been told a “tale.” All the stories about Law’s death at the hands of his men go back to Herrick. There is no record that anybody else ever related, or even heard about, this story independently of Herrick.

Herrick claimed he heard this story during a drinking bout in Albacete. But all the accounts of this “drinking party” go back to Herrick alone. No one ever heard of this drinking bout except from him. Stone and Cobert have explicitly denied it happened. None of the other alleged participants–Gordon, Roach, Mickenberg–seem to have ever mentioned it.

History as Fiction

One serious problem with the credibility of Herrick’s memoir is that he cites rumor, falsehoods, and his own (alleged) experiences indiscriminately. This practice inevitably casts a shadow of doubt on everything he wrote.

In Herrick’s “drinking party” story Hy Stone participated in the killing of Oliver Law because he had “lost his second brother to the war in one of the ambushes Law led them into.” But Joe and Sam Stone were in the Washington, not the Lincoln, battalion, and were killed in the same engagement and at about the same time as was Law. Neither brother could have been killed in any “ambush” for which Law was responsible. Hy Stone could not have blamed Law for the deaths of his brothers, as Herrick claimed.

Eby’s 1969 account, taken from Herrick, says that “Law’s body was left where it had fallen and was bloated by the sun into a horrible balloon.” Herrick himself told Berman in 1986 that “Later on they refused to bury him. He lay there for days.”

The earliest account of Law’s burial I can find is in Steve Nelson’s 1953 book The Volunteers. Nelson claims to have learned of it the same day it happened. In 1965 Arthur Landis interviewed Harry Fisher, who also gave an account of Law’s burial.

In the introduction to Jumping the Line Paul Berman called Herrick an “unstoppable truth-teller.” As we have discovered, nothing could be further from the truth. Not a single element of Herrick’s “tale” about Oliver Law is true. Not Law “leading his men into ambushes.” Not the “tale”–rather, multiple “tales”–about his death. Not the non-burial.

Not even the story about the “drinking party.” None of this ever took place. It is all Herrick’s fiction.

Did Herrick deliberately lie? Probably. His various “versions” are so changeable, mutually contradictory, and false, that the whole could usefully and accurately be termed lies. Herrick’s novels, memoir, articles, and interviews were–to use a slippery term from the commercial mass media–“based on a true story.” That story– the reality, the “truth” of which no one can ever deny–was his immense disillusion with the Communist Party and the communist movement. Tricked out as fact, and with the help of other bitter anticommunists, these stories serve as Herrick’s, and their, revenge. But no one should ever again confuse them with historical truth.

Grover Furr teaches at Montclair State University

Dear Prof. Furr. We exchanged some emails on this subject in Sept/Nov 2008. Back in May 2006, I sent a letter to Prof. James D. Fernandez regarding my late father, Lincoln vet Harry Hakam. Harry was a close friend of Harry Fisher, and they went to Spain together on the Ile de France, served together, and returned together as well. Both of them were there the day that Oliver Law died. In that letter, I recounted information from a videotape of my Dad (copies in the archives) in which he describes how he was running from a sniper and Oliver Law stood up and yelled at him to get down. In that act of compassionate concern for my father, Law (a big man) made himself a visible target and the sniper shot him. Actually, my father recounts this event twice, at different times, on the tapes. There is no commentary on these tapes about what happened after Law got shot, but it certainly puts the lie to the idea that Law was initially shot by one of his own men. I recently had my family’s personal copy of two of these tapes converted to DVD and will endeavor to find those segments. Thank you for seeking out the truth.

Herrick did not conclude that Herrick’s account was false – he merely pointed out inconsistencies between Herricks stories and observed his rabid anticommunism. Your rabid bias agaisnt Herrick tells alot about your bias.

Valerie – your hearsay account is hardly proof of anything.

Isn’t it interesting that one of the few traitors to the Lincoln Brigade would distinguish himself in this racist manner….the two make a great match, racists and professional anti-communists.

I remember how furious Harry Fisher was…he told this to me and my father Clarence Kailin…they were so close they shared phone calls weekly…..furious that Herrick’s lies would be dignified to the extent of meriting close examination, in “Odyssey of the Abraham Lincoln Brigade.” I think Harry felt that the approach was an expression of the distinctly American approach to Journalism known as “fair, accurate and balanced” or FAB. FAB requires that a universally recognized fact should get equal face time in a TV newscast as an obvious lie…the better to ‘balance” the story…and “let the public make up their own minds.”

Response to “Jorge”

I would hardly consider my father’s eyewitness account (he was right there when Oliver Law was shot!) to be hearsay. I was personally present when my father was being interviewed and recorded on videotape for the ALBA archives. He referred to that incident more than once over several days and hours, and his account(s) of the circumstances were consistent. The emotion in his voice and the tears in his eyes were genuine. He clearly believed he owed his life to Oliver Law.

I first met Steve Nelson and other veterans of the Brigade when Marc

Crawford brought me to their picket line in front of the Village Voice protesting the Herrick-based article smearing Oliver Law. Steve referred to as similar to the ranting of the slaveholder class against a black person of achievement. My initial encounter with Harry Fisher was in Madrid weeks later when I accompanied the vets on their 40th anniversary tour. Harry was vehement about the way “The Odessey of the Abraham Lincoln Brigade” gave credence to the Herrick story, even saying he had confronted its author demanding the story be removed from future editions. On many other occasions his anger would soar whenever he talked about the falseness of the Herrick story, and he would not let go of those craven enough to pass it on. Almost every time I met Harry sounded like the Ancient Mariner, furious about those who promoted the untrue Herrick tale. Over and over again he would say he knew from his experience with Commander Law that day the truth was entirely different. For an article I wrote for American Legacy and for the picture history of the ALB, he insisted on recounting in writing how Oliver Law died, how his men loved him, and he never stop voicing a sputtering fury against any individual who promoted the “Herrick lie.” By the end of his life he was still fighting for the restoration of Law’s great legacy, even though now it came out to his repeating, “I hate Peter Carroll.” I think he claimed he personally asked the author to or the author had promised to remove the Herrick tale. I do not know if this was true, but that was how Harry saw it.

I knew Steve Nelson in his later years slightly when I rented a house with some friends from him on Cape Cod. Though we disagreed on the split emerging in the USA Party we got along well for the brief time I was there. He told stories ranging from Harry Pollit (CPGB) to Oliver Law. Steve’s manner was genial save when he recounted the story of Oliver Law. I cannot remember his exact words but they certainly had the same anger that Mr. Katz describes

Personally I knew both Bill Herrick and Bob Gladnick, and despite their reputation with some of the more Party die-hards, these were two very brave men who were only shunned and smeared after they spoke out against the Hitler-Stalin Pact and Grover Furr’s major love of his pathetic life – that pockmarked Georgian Fascist named Stalin.

So personally I wouldn’t believe a damn word Grover Furr says. What I do believe is that Law was extremely incompetent, that his record at Jarama was spotty while Seacord and others went to their deaths, and that there are too many good vets who do claim he was “fragged”. Bernard Wolfe, Bill Herrick and others don’t tell lies or whitewash a bloody history. But Grover Furr do.

Just because a “good vet” claims Captain Law was “fragged” lends no credence to the Herrick lie. Historically, speaking the Fisher letter carries the most credibility and corroborative strength to the death of Oliver Law. I am also certain that in any such endeavor as the Lincoln Battalion there were a number of “good Americans” who resented Law’s leadership enough to sully his name after his death, in good American fashion of course.

[…] came against Oliver Law himself with later stories invented about him being shot by his own men. Grover Furr has responded to these allegations in the ALBA Volunteer. One must recall the times. No African-Americans had ever commanded white units in wartime and […]

[…] came against Oliver Law himself with later stories invented about him being shot by his own men. Grover Furr has responded to these allegations in the ALBA Volunteer. One must recall the times. No African-Americans had ever commanded white units in wartime and […]

I was finding this account incoherent, but only stopped reading it when I got to the following two paragraphs:

“The “officer’s runner” Herrick referred to must be Harry Fisher, who called Herrick’s story a lie. Rather than come to the defense of his own story, though, Herrick backed away from it: “I wonder if he [the runner, i.e. Fisher] had a criminologist with him at the front to examine Law’s body in order to determine where the bullet came from.”

That is, when confronted with eyewitness accounts of Law’s death Herrick responded: maybe one of the Lincolns had shot Law. He did not retract his claim that he had heard the “tale” of Law’s assassination by other Lincolns. But Herrick tacitly acknowledged it was false. By reducing the question of how Law was killed to one of where the bullet that killed Law had come from, Herrick tacitly conceded that the story he had told Wolfe of the “group action” did not conform to the facts.”

At this point it was clear that Grover Furr could not be relied on to retain logical coherence from one sentence to the next. Herrick’s dismissal of Fisher is not remotely what Furr claims it to be. He’s simply saying that if Fisher wasn’t there for the shooting then Fisher couldn’t possibly know what he claimed to know. The edifice Furr builds on this supposed “concession” is quite remarkable, and I will have no more of this nonsense.

A lot of talk about objectivity by the anti-communists here, but not a shred of objectivity from them. Grover Furr once again shows he is a historian and his critics aren’t. Like Grover Furr or hate him. Like Oliver Law or hate him. Like Joe Stalin — whatever he has to do with this — or hate him.

But facts remain facts.

The only clear eyewitness account that is publicly available is that Oliver Law was shot by a fascist while leading a charge. The rest is rumor, and shows the usual unreliability of rumor in that it has even changed in enormous ways over time.

No African-Americans had ever commanded white units in wartime as has been mentioned and I would tend to think from reading the is that there was some racism involved in this story. Oliver Law must have been Very difficult commanding whites who had brought their racism from America to Spain. We must also remember that during they were from a land where discrimination was the custom, segregation was the law of the land.Lynchings and castrations were all common place in America. Since #1 they were from America #2 the fact that there are lies about Oliver Law’s death sends a red flag up. In conclusion I would tend to think that Oliver Law was shot by a fascist while leading a charge or something that has not come-up in anything I have read is that someone murdered him because they didn’t like taking orders from a black man and it’s very possible that Oliver Law had to get tough with some of his troop because they failed to follow orders. I also read that Oliver Law was put in command because he was the only one that knew what he was doing.

Your review was written with a 2016 take on a 1930s war.

So Oliver Law was fragged. Well, at some point self-preservation kicks in, especially when two battles are lost due in part to poor leadership. It is enough.

That an officer was fragged, does not take away from the nobility of the cause and the volunteers during the SCW,nor is it a surprise that people on the left are capable of and can commit horrific acts.

Oliver Law was there as a volunteer and should be respected for this act and his sacrifice. That he may also have been incompetent and not fit for leadership does not take from his service.

Where is Oliver Law buried? Is there a photo of his grave?

[…] there were a number of African Americans. Most famously the Texan military veteran and Communist, Oliver Law, became the first Black American to command white troops in battle; when he was tragically killed […]

[…] de muerte mientras dirigía un asalto al llamado Cerro del Mosquito . Años después, como recoge The Volunteer circuló el rumor malintencionado de que había sido víctima de algunos de sus propios […]

[…] de muerte mientras dirigía un asalto al llamado Cerro del Mosquito. Años después, como recoge The Volunteer circuló el rumor malintencionado de que había sido víctima de algunos de sus propios soldados, […]

Regarding the photo of “the ester carriers”, that certainly is Oliver Law,as he is wearing a teniente’s galleta on his breast pocket.